Myanmar: Filming the Coup

Participants in story-telling project empowered to alert outside world and fellow citizens to the country’s plight.

Reliable information remains scarce in Myanmar, where four months after the military coup, peaceful protestors continue to face violence that has already left more than 700 dead.

A story-telling project originally intended to train ordinary people to produce short films is now also generating powerful videos to alert the outside world and their fellow citizens to the country’s plight.

It has provided a rare means of communication and genuine documentation amid the political and disinformation crisis.

“Access to information is very, very important because it can save our lives.”

Aye, Project trainee

The work is part of a partner project supported by IWPR - which cannot be identified so as to protect local participants - ongoing in five countries across the region.

Following the coup, the project quickly pivoted to adjust to the changing realities in Myanmar, introducing extra security measures such as a proxy website and further encryption.

“Access to information is very, very important because it can save our lives,” said one trainee, Aye, who was in the final year of her English degree before the coup (all names have been changed for security reasons).

She has been forced to abandon her studies and move house for her own safety.

“I could film [more easily] at the beginning of the coup, before the military, the state sponsored terrorists, had started mass murdering people,” Aye said. “Currently, it’s very difficult even to go out with your camera on. People will suspect you are a military informer… And if someone from the military sees that we are filming, they would follow, then arrest us.”

On February 1, the Tatmadaw military staged a coup following the landslide election victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party.

The takeover plunged the country back into military rule after a decade of progress towards democracy, with commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing seizing power. NLD officials were detained, including Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint, and street protests and civil disobedience movements are met with brutal suppression.

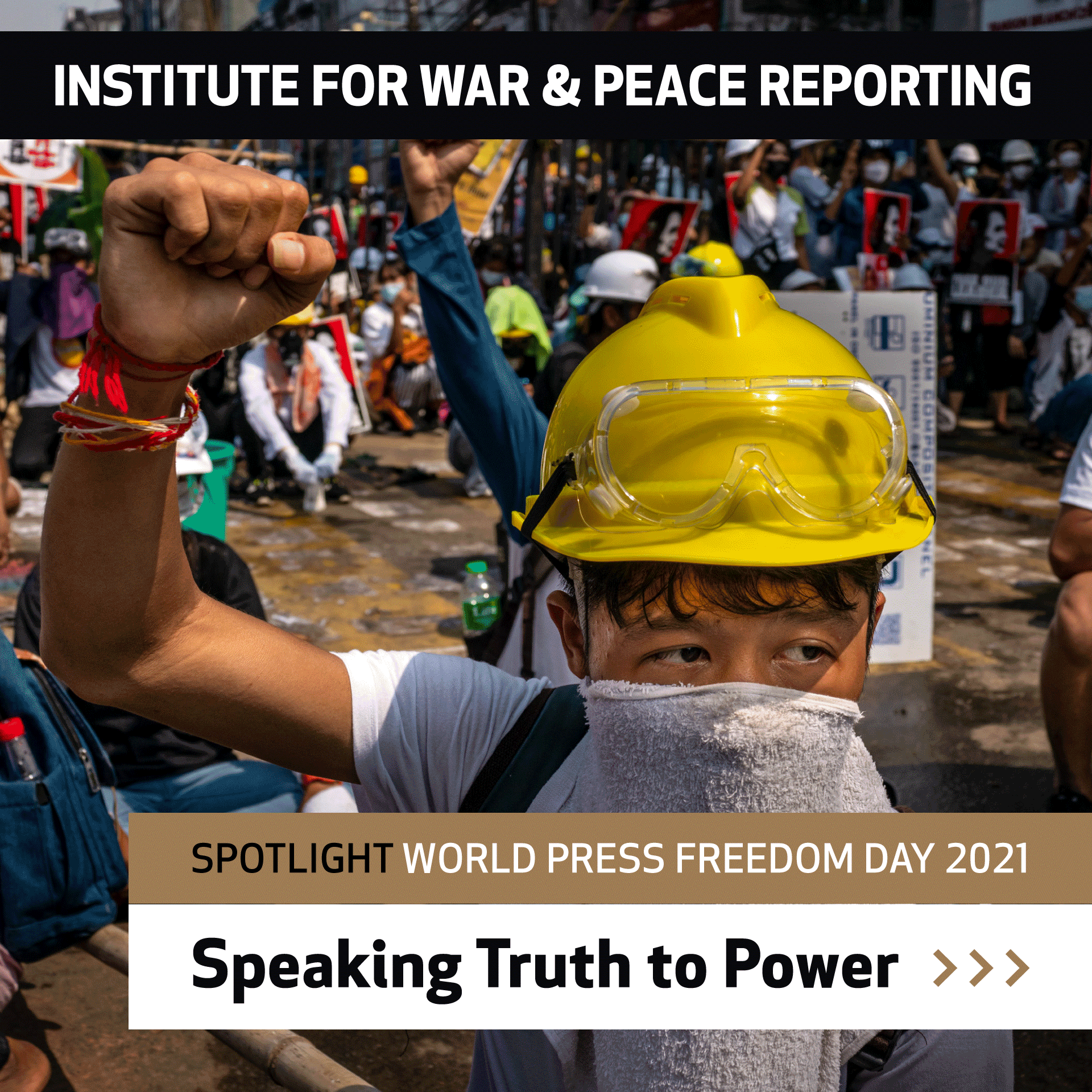

The people continued to defy the junta by staging mass protests and strikes, despite ongoing violence and harassment.

Kyal Lin Htet, a second-year psychology student, documented the historic February 22 nationwide strike, which saw millions of people taking to the streets to call for an end to the military regime.

“In the strike, the people were burning the 2008 constitution book after getting the announcement of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw - our elected government - that the 2008 Constitution [which strongly supports the military’s influence] no longer works in Myanmar,” he said.

The crisis has already displaced nearly a quarter of a million people, according to the UN, with its special envoy for Myanmar Christine Schraner Burgener warning that “a bloodbath is imminent” with a civil war on “an unprecedented scale”.

For participants in the video-making course, their new skills are a way to let the international community know the gravity of their situation, as well as documenting ongoing rights violations and communicating with others on the ground.

Their material is a rare source of credible information amid the regime’s ongoing disinformation efforts.

“Access to information is very important… but we are not journalists,” said Maung, previously a government official with a medical background. The training quickly showed him that he could nonetheless use the tools at his disposal to not only broadcast to the outside world but also post real-time information to warn others.

Maung said that that the format was empowering, demonstrating that “everybody has a right to access to information”.

So far, he has focused on the protests, shootings, and house raids in his own area, collecting documentary footage of the turmoil.

“Near me, there are so many protesting and so many shootings,” Maung said. “There are so many displaced persons.”

The junta, already severely restricting access to the internet, shut down wireless broadband in early April.

Aye said that those still with access had a responsibility to find and share information.

“Because of the current situation, only a few percent of people have fibre internet, and they have the chance to know what’s happening in different places of Myanmar and tell the world what is happening.”

All three have become mentors to their fellow citizens, going on themselves to conduct trainings despite limited internet connection. As Maung notes, being able to train in the local language made communication much easier.

“We send text messages, we call them,” continued Kyal Lin Htet. “We talk with them every day to keep them attending our class and to keep learning.

Their trainees in turn have gone on to shoot, edit and post their own videos that encapsulate short but powerful messages.

“Presenting our information effectively - and also attractively and interestingly - in a short time can help get the audience’s attention,” Aye continued. “I think this kind of skill is essential in the current situation. If we can teach the students how to do powerful, short videos, then we can share what’s happening here with the world.”

Aye had planned to work in an international NGO after graduation, before taking a masters in social work.

“What I intended to become in my life may not be possible now,” she said. “Maybe I have to go to a developed country and do basic work like washing dishes or something like that.”

The ongoing violence, she said, “destroys our future”.