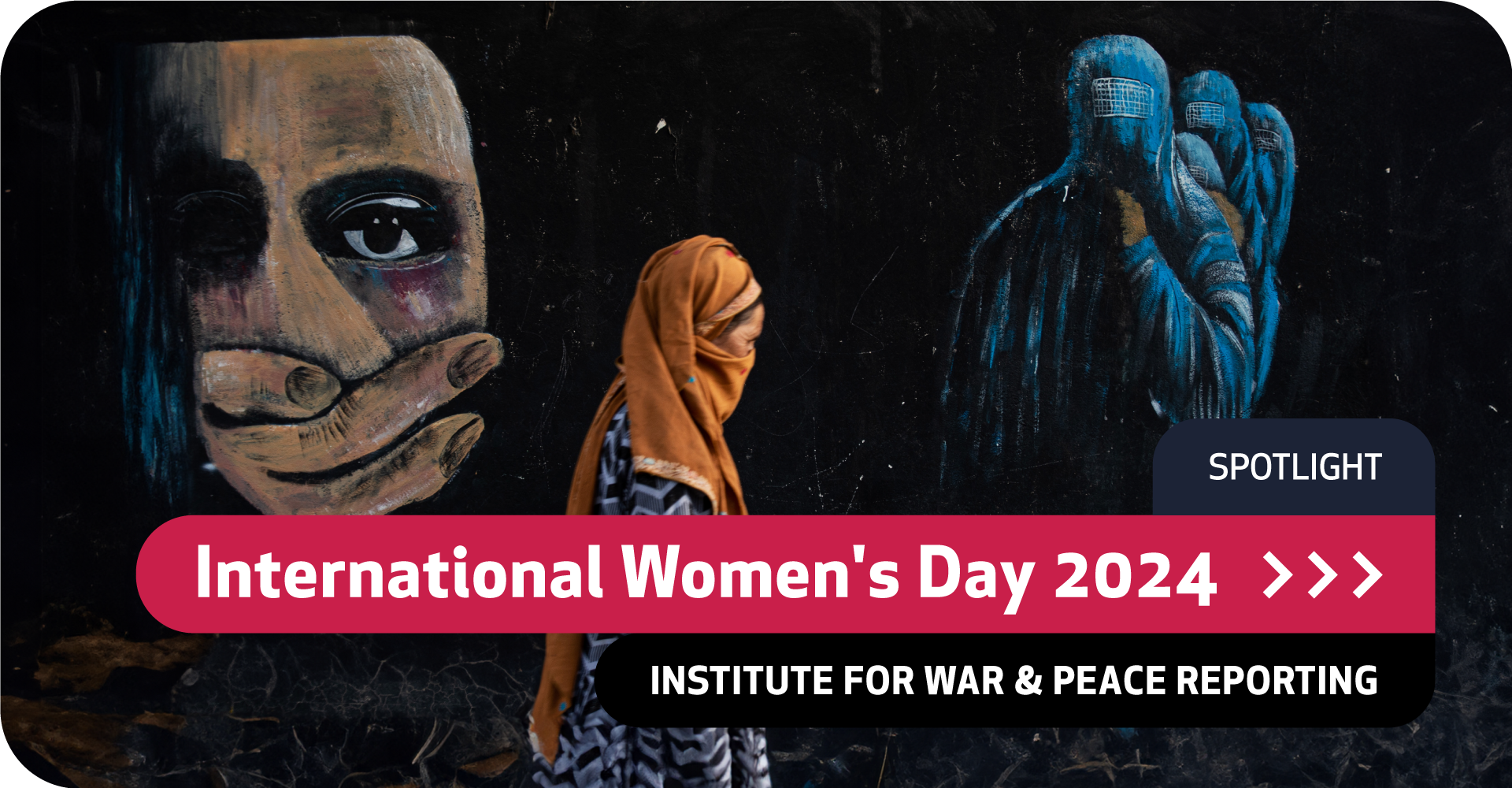

Afghanistan: “I Don’t Want to Live. I Want to Die”

Two decades of efforts to protect women and girls has been systematically dismantled.

When Tahmina’s father realised the Taleban were on the verge of returning to power, he quickly married her off to a man whose family had ties to the militants. Aged 17, she moved into her husband’s family home in the Dand-e-Ghori district of Baghlan province, in the north of Afghanistan.

There, she was abused from the moment she stepped over the threshold. Her husband slapped, punched and beat her, often at the urging of her father-in-law. Her new family mocked, humiliated and abused her.

Life became even more unbearable when Tahmina’s husband was ambushed and killed by bandits. His father insisted that the young widow, then the mother of a two-month-old boy, marry her husband’s eight-year-old brother. When Tahmina refused, he killed her infant by cutting his throat.

"Afghanistan has become a hell for women,”

“The horror and anger I’ve experienced are so overwhelming, I don’t want to live. I want to die,” Tahmina said. She said that she could not seek justice because her father-in-law had close ties with the Taleban.

Afghanistan already had a high rate of violence against women before the August 2021 Taleban takeover. Under the re-established regime, the situation deteriorated even further. All legislative gains made in the previous two decades to protect women were quickly destroyed.

The vast majority of the 60 women interviewed for this article from across 17 provinces in Afghanistan reported being subjected to violence, including physical torture, verbal abuse and forced labour. Only eight had lodged formal complaints with the authorities.

“It’s both horrifying and unsurprising that violence against women would have increased after the Taleban takeover,” said Heather Barr, the associate director of the Women's Rights Division at Human Rights Watch. “One of the Taleban’s first actions—one of their most urgent priorities—was systematically dismantling the entire system that had been put in place to protect women and girls from violence. This system promised women and girls some autonomy, ability to make their own choices and demand their rights—the Taleban can’t stand that.

“Their vision of society is one where women and girls are the sole property of their male relatives, entirely at their mercy, and are removed from public life—and they have largely achieved that.”

Indeed, given the official restrictions on women’s freedom of movement, most women have effectively been trapped in their homes, often with violent spouses or in-laws. Of the women interviewed, one in five said that they had contemplated dying by suicide, while two had attempted to kill themselves.

“In the Taleban’s view, it is not necessary for women to go to court."

Shafiqa, an 18-year-old from Firozkoh city in Ghor province, recounted how she had been forced to marry a much older man who already had a wife and four grown-up children.

“Sometimes his children hit me, and when I complained to my husband, he said it was okay if they hit me; I must have done something wrong,” Shafiqa explained. “Once, when I argued with his other wife, he cut branches from the trees inside the courtyard and beat me severely. My whole body was black with bruises and I was in pain for a week.”

“I got very tired of life,” she continued. In desperation, she collected all the tablets she could find in the house and swallowed them. Instead of dying, she became sick and vomited the pills. After her condition improved, her husband beat her for dishonouring his reputation.

Afghanistan has been ranked as the worst country for women in the world, according to the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Index. The Index, which measures the status of women in 177 countries, considers indicators such as economic, social and political inclusion as well as justice and security.

“Afghanistan scores lowest on this indicator, with its score of 0.37 driven by the Taleban’s oppressive regime that has severely restricted women’s ability to safely and fairly pursue justice,” the Index report read.

A January 2024 UN human rights highlighted “a lack of clarity regarding the legal framework applicable to complaints of gender-based violence against women and girls in Afghanistan, including which de facto justice actor is responsible for each action along the justice chain regarding such complaints”.

The report emphasised that “many survivors reportedly prefer to seek redress through traditional dispute resolution mechanisms because of fear of the de facto authorities”.

“A Hell for Women”

Fanoos, one of a family of ten in Jawzjan province, was a keen student who went on to gain a bachelor's degree from a private university. After graduating, she soon got her first job on a development project.

She was proud of her achievements and her career. But her independence abruptly ended when the Taleban banned Afghan women from working for NGOs, the UN and many other roles. Fearing for her safety as a former employee of the previous government, Fanoos’ parents coerced her into an engagement with an Afghan man she had never met and who lives in Turkey.

Every time she has suggested ending the engagement, her father and brothers have physically abused the 23-year-old. Her mother has also refused to help.

Fanoos’ despair was so bad that she slashed her wrists with a knife, losing consciousness before her sister discovered her.

“Women have no right to work, choose a life partner or access education. Afghanistan has become a hell for women,” she said. “In these difficult and dark circumstances, we can’t complain to anyone about our family problems because, to them, beating women is normal.”

“In the Taleban’s view, it is not necessary for women to pursue legal options and go to court. Even if they face violence in the family, it is either justified or they need to deal with it privately, within their family,” said Shaharzad Akbar, former chairwoman of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, adding that the Taleban saw “no role for judiciary system in protecting women from violence”

“There is no formal door to knock at, except the family, if they are supportive,” said Akbar, now executive director of Rawadari, a new Afghan human rights organisation.

UN experts also link the Taleban resurgence to rising rates of child marriage, which puts girls at a particular risk of gender-based violence perpetrated with impunity.

Aged just 15 years old, Nazanin has found herself trapped in a life she did not choose. She was forced to get engaged at 13 and married off at 14. She lives in Sheberghan city in Jawzjan and envies the girls she sees playing in the alleyways near the house she shares with her 16-year-old husband, who buys and sells scrap iron for a living, and his family.

“He uses half the income he earns to buy cigarettes and gives the rest to his father. He doesn’t give me any money even though I need it,” she said. As a result, although Nazanin is heavily pregnant with her first child, she is not allowed to rest. Every day, she must repeatedly lug two 10-litre containers of water back from the village pump. Every night she worries about the future – hers and that of her unborn baby.

“Sometimes, when I think about leaving home, I wonder where I could go and who would take my hand and provide a better life for me. I have no one,” she said.

This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in Zan Times, an IWPR media partner. Mahtab Safi and Mahsa Elham are the pseudonyms of Zan Times journalists in Afghanistan. Freshta Ghani is a journalist and editor at Zan Times.