“The Space for Abuse Seems Endless”

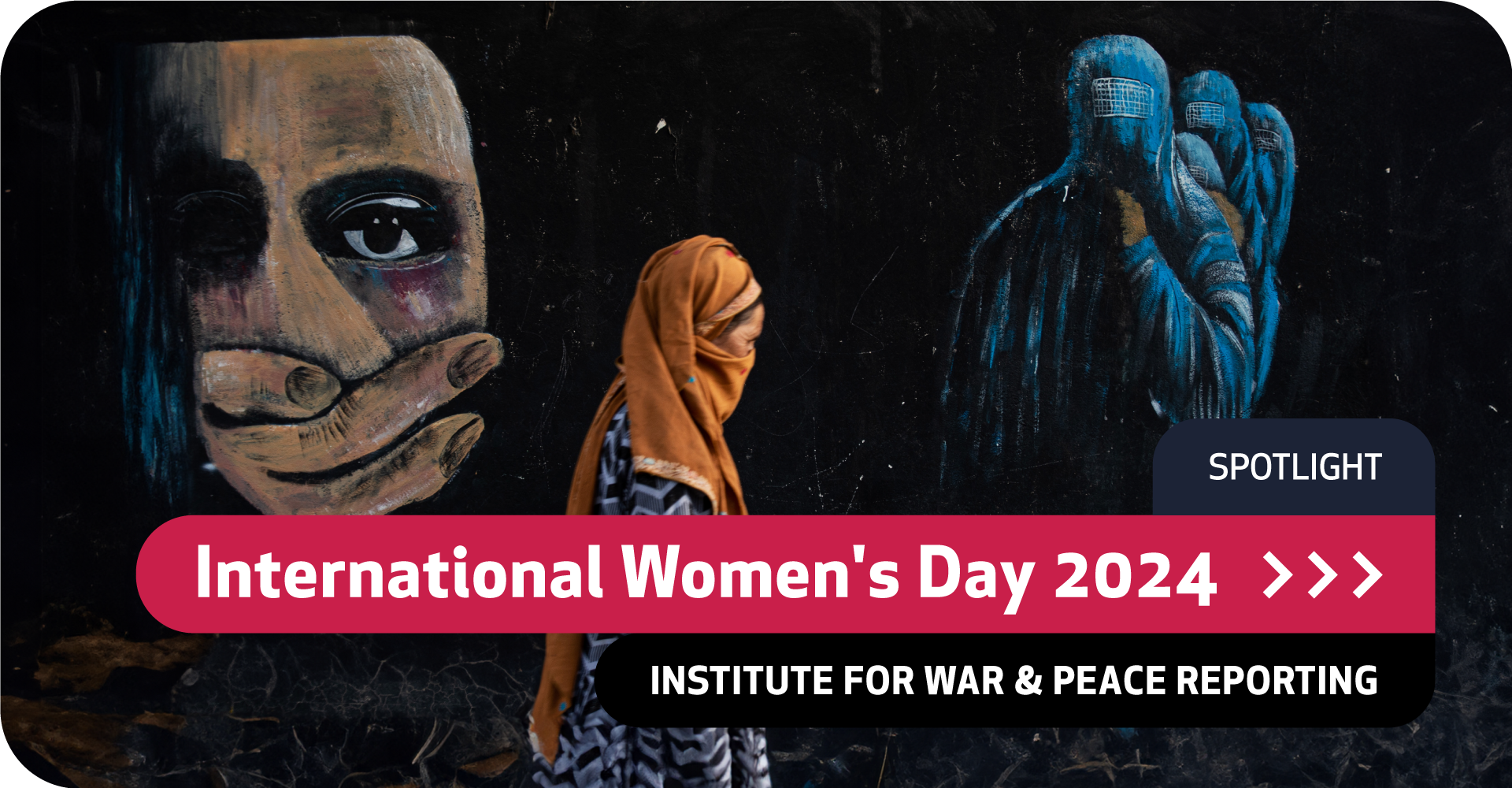

Gender disinformation aims to create a hostile environment for women with the goal of shaming, intimidating, silencing and excluding them.

I am a woman of colour and a rights activist who has experienced every form of online abuse imaginable for over a decade. So let me tell you how this particular form of violence makes victims feel.

We feel alone. We feel powerless. And we feel scared, ashamed and frustrated.

Amidst all the slogans of solidarity that are bandied about and well-meaning insistence that there is no space for online violence against women and girls, the reality is that the space for abuse seems endless.

The flood of misogynistic threats we face are often sexualised and specific to culture, ethnicity and background. Such gender disinformation is a form of violence that weaponises gendered narratives. The attacks are even harsher when targeted at women of colour, non-gender conforming women and women of diverse identities and backgrounds. Some of those most affected are journalists, politicians and human rights defenders.

"My first reaction to the online abuse that I experienced was to try and disappear."

And while individual women may be targeted, the wider message is that women as a group should not be involved in the public arena. The goal is to create a hostile environment for women and girls with the goal of shaming, intimidating, silencing, and excluding them.

Many of us fall into that trap, at least initially. My first reaction to the online abuse that I experienced was to try and disappear from the internet; no social media, no pictures, no posts or any type of content under my name for years. In short, I self-censored. And while that’s understandable, it is the worst thing we want to do as activists, journalists, politicians and as actors of change in general.

These attacks exploit sexist and misogynist narratives to frame women as unfit for leadership, untrustworthy, unqualified and unintelligent. While some of these attacks are perpetrated by individuals, others are coordinated campaigns which employ various disinformation tactics.

“I do not know a single woman journalist, activist, or politician who has not been targeted online.”

At times, these are orchestrated against a specific woman or a group of women actors of change with the intent of manipulating public perception and pushing them into a dark corner where they are forced to be silent.

In 2020, for instance, Ghada Oueiss and Ola Al Fares – two Al Jazeera journalists who covered the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi – were subjected to an online smear campaign by thousands of verified Saudi Twitter users. Both were inundated with a barrage of sexual allegations and innuendos.

In Oueiss’ case, the online violence threatened to spill offline. A Facebook post offered 50,000 US dollars to “anyone who would kidnap or kill” her. The perpetrator was eventually arrested yet the threat remained on Facebook for some time, increasing the physical danger she faced.

This provides a clear illustration of a phenomenon that most of us still do not understand - these threats are not restricted to the online sphere. Often, they are translated into the “real world” further restricting the most basic of human rights for the victims and excluding them from the public arenas.

Tunisian blogger and human rights activist Lina Ben Mhenni – who died from a chronic illness in 2020 – told the BBC that the threats she received via text message and Facebook were not restricted to the online space. "I have often been harassed by hardliners on the streets physically and verbally,” she said.

Tunisian lawyer and politician Bochra Belhaj Hmida also told the BBC how she had been subjected to "harassment, smear campaigns, defamation, death threats and calls for my assassination”.

And this violence goes beyond the individual to target families, friends, colleagues and any institution perceived to be affiliated with them. This puts further pressure on the woman in question to withdraw from the public arena, especially those in the more socially and religiously conservative parts of the world.

Well-known Lebanese journalist Dima Sadek, a vocal supporter of the anti-austerity protests that swept Lebanon in 2019, was subjected to intimate pictures of herself being sent to her mother that year. (More recently, Sadek was sentenced to a year in prison for defamation after accusing a prominent politician of racism).

At a societal level, gendered disinformation deters women’s freedom of expression and undermines the very basic pillars of democracy and human rights, impacting the hard-earned right to participation and inclusion in the public, social and political arenas. For those who resist, the consequences can be cruel.

Another Lebanese journalist Luna Safwan, was one of seven women who in 2021 took legal action against a well-known local activist and director for harassment – and in turn had several lawsuits filed against her in an attempt to silence her.

In fact, I do not know a single woman journalist, activist, or politician in the MENA region and elsewhere who has not been targeted online with sexist, misogynistic and racist lies specifically meant to silence her. Just in my immediate circle, I can think of at least 20 examples of women human rights activists who were targeted online at one point or another.

My message to the cowards hiding behind screens is we will not go anywhere, and you will not silence us. And my message to the women and girls who have been subjected to any form of online gender-based violence, is that there you have the support of millions in your position all over the world. Do not let anyone silence your voice. We will continue the fight and we will win.