Death Flights in the Amazon

Year-long investigation reveals extent of narco airstrips as drug-traffickers terrorise Indigenous communities and destroy Amazonian rainforest.

PART I

A distressed voice speaks on the other end of the phone, calling from an Indigenous territory in the Peruvian Amazon.

“They are trying to take off again; please tell the Dirandro [Peruvian National Police]. Please, I do not want to have problems in my community,” an anonymous member of an Indigenous community says.

The caller requests the presence of officials from the antidrug department of the police while watching an unknown airplane in the distance, hidden in the forest.

In the darkness, without anyone being able to see him, he anxiously recounts that a group of men prepared a shipment of drugs on an illegal airstrip built in his community’s territory. His desperation is evident, especially because he knows that his community is facing a gigantic monster embedded in Ucayali, a region that has become a new hotspot of drug trafficking in the country.

This call for help is one of many that are coming from several Indigenous communities in the Peruvian rainforest that live surrounded by illegal activity. The leader who had the courage to talk is one of the more than 60 journalistic sources interviewed by Mongabay, as part of a year-long investigation that managed to confirm the existence, and the episodes of violence behind the use, of 76 unauthorised airstrips in six Amazonian regions: Ucayali, Huánuco, Pasco, Cusco, Madre de Dios and Loreto. Sixty-seven of them were in the first three regions, where the majority of Indigenous leaders have been killed in the past four years since the pandemic.

Each of these illegal airstrips in the forest was detected or corroborated by Earth Genome, an organisation based in California in the US, specialising in satellite image analysis. Mongabay’s collaboration with Earth Genome is supported by the Pulitzer Centre. The reporting team developed a search tool called the Earth Index that used AI to review large volumes of satellite images to detect clandestine airstrips in the Peruvian Amazon.

For the analysis to work, the team gathered and combined information from OpenStreetMap with data from official airstrips reported by the Ministry of Transport and Communications and with samples of narco airstrips identified by Dirandro and the Regional Government of Ucayali. With all these training data, a computer vision AI was able to track similar patterns in the territories Mongabay investigated.

Artificial intelligence is “asked to look for similar characteristics in the satellite images”, explain the specialists, who set themselves the task of detecting new illegal airstrips hidden in the forest.

“Locating an airfield from space in the Peruvian Amazon is like finding a toothpick hidden in a misshapen soccer field, like locating it among the grass, weeds and bare earth.”

Once the satellite analysis was complete, each potential airstrip detected was verified with local and official sources by Mongabay, which confirmed the location, extension, use, date of opening, presence within prohibited areas (such as protected areas, Indigenous reserves and forest concessions), as well as the proximity to roads and rivers.

Satellites, which repeatedly take photographs of the planet, make it possible to clearly establish timeline details such as when a clandestine airstrip was opened, since it is enough to compare the airstrip detected by the search tool developed with AI with a previous image of the same place when the forest was still standing.

The satellite analysis of the airstrips that were detected confirms the existence of drug-trafficking routes that are outside of authorities’ control. The ease with which the destroyed airstrips are rebuilt is proof of this. According to Peruvian National Police Colonel James Tanchiva, head of the Division of Maneuvers Against Illicit Drug Trafficking in Pucallpa, drug traffickers barely take a week to resume their operations if their airstrips become disabled.

“The organizations that traffic drugs have good logistics, have their militant branch and have money. That is the reality,” Tanchiva added.

The reality also indicates that this illegality goes beyond drug trafficking.

“We are in a period when crimes in Peru are converging, because this is no longer just a drug-trafficking issue, but [an issue] of several crimes that are being managed and run together,” said Luisa Sterponi, Peru project coordinator from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

A report from June 2024, which Sterponi co-authored, stated that in the last three years, annual forest loss and the number of confiscations of illegal timber have increased, and there has been an intense expansion of illicit coca crops.

“The number of laboratories for processing cocaine byproducts destroyed by the antidrug police has been the highest in the country, accompanied by an exponential increase in unauthorised airstrips,” it noted.

Surviving in the ‘Triangle of Death’

The bleak outlook created by the drug airstrips is clearly visible in the Huánuco, Pasco and Ucayali regions. In fact, the Earth Index revealed a high concentration of unauthorized airstrips in a space that could well be called the “triangle of death.”

These airstrips and illicit coca crops are the scene of the killings of at least 11 Indigenous leaders and community members, according to the National Coordinator for Human Rights (CNDDHH), although that figure is 15 according to the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP).

Sources from the area, however, say that some additional deaths that went unreported for fear of retaliation.

“I know of two Indigenous brothers murdered in 2023 and one who has disappeared this year,” said a leader of an important Indigenous federation in the area, who asked to remain anonymous. The bloodshed and disappearances are part of the violence endured by 28 Indigenous leaders who are under threat in the three regions, according to the mapping completed by the AIDESEP Regional Organization of Ucayali.

Not only do the illegal airstrips cut through land and drive deforestation, but they also sow seeds of terror. The satellite images provide concrete evidence of this reality. Of the 67 narco airstrips detected by the Earth Index in Huánuco, Pasco and Ucayali, 30 are within Indigenous communities and 26 are in areas that surround them. Seven territories have not only been invaded by airstrips, but are also surrounded by them.

Another relevant fact: The coca crops in the three regions span a total of 18,742 hectares (46,300 acres): 12,221 (30,200 acres) in Ucayali, 4,960 (12,250 acres) in Huánuco and 1,561 (3,857 acres) in Pasco, according to the most recent coca monitoring data from the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA). In the case of Ucayali, coca production tripled since 2020, and in Huánuco, it doubled.

To get a clearer idea, this is an area 76 times the size of the Cusco historic centre.

The investigation also allowed researchers to confirm that the 67 unauthorised airstrips are used for drug trafficking. At least 50 people interviewed — including local and official sources, in addition to important leaders from three Indigenous federations in the Peruvian Amazon — were the key to determining the airstrips’ precise use.

In the middle of these drug trafficking routes live Indigenous communities whose members were distraught as they described the abrupt cultural shift that has been brought to their land.

Some communities have needed to share their territory with tenant farmers who work with illegal crops. They are responsible for transporting drug shipments, guarding laboratories or preparing new airstrips. Silence is the only way to survive when people witness these scenes. Meanwhile, they must become accustomed to their routines coming to a halt with each flight.

“When an airplane is going to land to be loaded with drugs, all traffic stops. The population, too. It does not happen very frequently, but that is how we live,” said an Amazonian leader who lived in a community in Atalaya province but had to abandon his territory for safety.

A calculation by Mongabay, based on data from the satellite monitoring platform Global Forest Watch, shows that to build the more than 67 airstrips, at least 109 hectares (270 acres) of rainforest had to be deforested. However, Sterponi of UNODC Peru explained that the presence of unauthorised airstrips in Amazonian communities have consequences beyond the environmental impact of deforestation.

“The construction of an unauthorised airstrip is much bigger than what one can imagine,” she continued. “They have a direct impact on deforestation, but the real impact is broader and also involves social aspects.”

AIDESEP vice president Miguel Guimaraes is convinced that the fight against illegality cannot be based exclusively on repression.

“This is not just about trying to drive out the people who work in illegal activities, but to [ensure] that that site is not invaded again and that they don’t return, concrete social and civil actions must be carried out,” Guimaraes said. “[Otherwise] it is very easy to reopen the unauthorized airstrips that were destroyed, because in that area (Ucayali), in the next five years, the authorities will not enter again.”

Residents of two communities located between Huánuco and Pasco live alongside 15 drug airstrips in and around their territories. The oldest of these airstrips was opened in December 2015, and the newest was opened in February 2023.

“There are airstrips, not inside the community, but around it. The government knows how many airstrips there are and where they are. In Constitución, there are more than 100,” an Indigenous leader from the area said.

The two communities that Mongabay visited have the misfortune of living in the middle of one of the drug-trafficking routes that begins in the city of Constitución.

According to Florencio Carrillo, an official from the La Merced Zonal Office of DEVIDA, Constitución is an axis of drug trafficking where “all evils” come together and “violence, extortion and murder” are part of the routine. The communities also live in a central area of the rainforest, where the subbasins of the Pichis, Palcazu and Santa Isabel rivers and part of the Pachitea River converge.

What factors are behind the increase in unauthorised airstrips in this area? In the face of political and military pressure in the Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro River Valley (VRAEM) — where more than 38,000 hectares (93,900 acres) of coca crops are concentrated (the largest amount on a national level) — criminal groups need to move their drug transportation to another point. These new commercial spaces are what we call the “triangle of death” and where a so-called “balloon effect” can be seen. In other words, when one section of a territory is pressed on, the activity immediately moves to another section.

Nicolás Zevallos, public affairs director at the Institute of Criminology and Violence Studies, explained that the area provides two advantages. The first is the logistical and operational ease of transferring drugs from Peru to Bolivia, due to the proximity of this area with the neighbouring country. The second advantage is the possibility of evading police and military control.

“Operating inside the VRAEM, which produces much more cocaine than the rest of the entire region, is almost impossible in terms of flights and mobilisation; therefore, it is much simpler to move two or three districts higher and put the available airstrips in the areas of Atalaya, Pichis-Palcazu-Pachitea and Aguaytía,” Zevallos said.

This is why gangs search for the most remote and least accessible, places, such as Indigenous communities and reserves for Indigenous peoples living in isolation.

In the Native communities that surround the Kakataibo Indigenous Reserve, the Earth Index detected three unauthorised airstrips: one inside the reserve itself and one around it, both in the northern part; and another one very close to the southern part of the protected territory. This was verified by a team of journalists who travelled to that area.

Three other landing strips were confirmed in two Indigenous reserves: one in and around the Murunahua Indigenous Reserve and a third around the Kugapacori, Nahua, Nanti Territorial Reserve. In these areas, strips of deforestation can be easily seen close to rivers and in the middle of a dense forest.

“It is terrible that there are unauthorised airstrips in so many Indigenous reserves; that means that the government cannot guarantee the effective protection of any of them,” said Vladimir Pinto, Peru field coordinator for Amazon Watch.

In a community near the Kakataibo North and South Indigenous Reserve, an Indigenous leader told Mongabay that “their territory is cornered” and that local and regional authorities do not attend to their complaints. Only the Indigenous guard is making an effort to liberate their communal territory from the presence of drug trafficking and other illegal economies. This is repeated in each of the communities adjacent to the reserves of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact.

“The Indigenous guard conducts inspections, destroys maceration pits and burns crops, but there are so many,” a source in the territory said.

The Business of Narco Airstrips

Residents of the province of Atalaya, in Ucayali, are very familiar with how drug traffickers operate. Testimonies describe this industry as a planned and well-articulated business, and one in which airstrips play a fundamental role. In fact, Devida considers Atalaya to be one of the places with the highest concentration of unauthorized airstrips in the entire country, and it is one of the territories in which the algorithm detected one of the highest concentrations of illegal airstrips.

A person can only travel to Atalaya with warnings: Do not talk to strangers, only travel with others, stay for a short time and always try to remain unnoticed. The point is clear: Don’t trust anyone. Once in the area, these warnings are no longer an exaggeration. For Mongabay journalists, they prefaced the difficulty of finding sources willing to talk. Most of them asked to remain anonymous.

The team of journalists managed to travel to an unauthorized airstrip that was recently built on cleared land.

A source said,“It is 985 meters [3,200 feet], a big cancha [soccer field],” as many call the narco airstrips in this part of the Peruvian Amazon.

The people in charge of “facilitating” the arrival and departure of the airplanes loaded with drugs are often people who live in the area and who have managed to settle inside these Native communities, according to a motorcyclist from the area. This work involves ensuring that the drug traffickers have an unauthorised airstrip available to them so that each operation can be carried out without any issues.

“Every day, up to four flights can take off. At times, while one airplane is being loaded with drugs, another is taking off. Each operation should take five minutes at the most. So, one single organization could leave with up to 1,200 kilos [2,645 pounds] of cocaine per day,” a local source said to a reporter who visited Atalaya.

The 31 narco airstrips detected by the Earth Index in Atalaya province are only one aspect of the situation. The worst is endured by the Indigenous communities when they resist or oppose the illegal operations. They become an obstacle for gangs — even more so because 13 of the 31 illegal airfields in Atalaya are within their territories and 13 are surrounding them. In many cases, community guards are the first line of defence.

However, combating such a powerful adversary without help is impossible. Criminal organisations, according to experts, often restructure themselves and change their strategies. Now, for example, they outsource some of the tasks in their chain of illegal activities, which makes it more difficult for the police and the army to track down those responsible.

An initial transformation occurred with the arrival of Mexican cartels, which led to the use of an outsourcing system, according to Zevallos.

“Now, it is even more fragmented, to the point that it is basically brokers who control the transport of drugs from one point to another, but they do not have complete control of the entire chain. Instead, they use various suppliers,” Zevallos said. He added that in Peru, although there are some large laboratories that produce cocaine, the vast majority are small laboratories that produce smaller amounts of drugs that are collected until they get a “kind of important” shipment.

Zevallos explained that for this fragmented system to function, transnational criminal organisations send a person who serves as a connection with drug-producing countries, such as Peru. That person hires and coordinates with those responsible for collecting and transporting the drugs, then leaves.

Sterponi of the UNODC agrees that different phenomena related to drugs are being observed. These include the appearance of smaller specialised criminal groups that provide services directly to drug traffickers, as well as cross-border criminal groups, such as the Comando Vermelho and the First Capital Command which are entering Peruvian territory through Brazil.

“Those criminal groups dedicated to illicit drug trafficking are also focused on other crimes,” she said. “The convergence of crimes within organized crime groups is increasing very much.”

Noam López, a lecturer at the School of Government and Public Policy at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru and safety researcher at the Institute of Social Analytics and Strategic Intelligence, attempted to summarise it.

“There are organised crime groups set up in the country that are in all the illegal economies at the same time,” he said. “What should be kept in mind is that these people have knowledge of the territory and they know how to deal with the authorities.”

López explained that there is usually a leader who develops a strategy, and if it is successful, he replicates it time and time again.

“A leader organises all of these activities. So, imagine that he has a group of 30-50 young people who have knowledge of the territory. When he does well in one place and has everything organized, he goes to another area. That is what is happening.”

The transfer of knowledge is quick and if anyone dies, that person is replaced immediately, because there are other people who already know the system.

“This is why if you destroy airstrips, they return to rebuild them and fly airplanes very quickly.”

The strategy, according to López, includes the creation of money laundering companies.

“Our attention must be on organised crime, money laundering and everything that has to do with illicit [financial] flows because it is an international and multi-product business,” Sterponi added.

Where do the drugs originating in this area of Peru go? An agent from the tactical operations area of the Division for Maneuvering against Illicit Drug Trafficking in Pucallpa told Mongabay that Cessna airplanes — displaying the Bolivian flag — land in Atalaya to transport shipments of between 300 kg and 350 kilogrammes of cocaine. They are often headed for the department of Beni and, in some cases, after stopping in that northern Bolivian region, they continue flying toward Brazil. At times, they also fly to Colombia, according to Tanchiva of the antidrug department in Ucayali.

In response to a request for information, the central office of the antidrug department of the Peruvian National Police stated that between 2013 and 2022, they destroyed 705 unauthorized airstrips in the regions of Huánuco, Pasco and Ucayali. These interventions increased between 2019 and 2020, the most critical years in terms of the pandemic and of the violence in those territories. Additionally, 12 small airplanes destined for drug trafficking in the three regions were destroyed, and 19 aircraft were reportedly damaged between 2012 and 2022.

‘High-flying’ Concessions

“They should create a VRAEM [a term used to refer to the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro River Valley ]-type operations centre in Ucayali because drug trafficking is now unsustainable. We have learned to coexist, as long as we do not interfere with them,” the representative of a forest concession in which an unauthorized airstrip was detected said to Mongabay.

Despite the complaints reported by the representative, he claimed that authorities had not taken action.

Upon viewing the satellite images of the drug airstrips detected inside forest concessions in Ucayali, it is notable that there are patches of illicit coca crops overlapping in them. Six of the 10 illegal airstrips in the provinces of Atalaya, Coronel Portillo and Padre Abad are in the middle of coca crops.

The analysis showed that within a 2-kilometre radius, there are at least 27 hectares of illegal crops bordering the drug airstrips. This is almost 38 times the area of the National Stadium of Peru.

Rolando Navarro, the former executive president of Peru’s Agency for the Supervision of Forest Resources and Wildlife (OSINFOR) and expert from the Centre for International Environmental Law, said the presence of drug airstrips and illegal crops in forest concessions may be a serious indicator of the link between illegal logging and drug trafficking.

“The holders of the concessions are custodians of the forest and are responsible for informing authorities and filing a complaint when there is an invasion and when they encounter illicit crops or unauthorized airstrips,” Navarro said. At least six of the nine holders reported findings and said the authorities did not attend to their complaints, according to reports from OSINFOR. It is worth noting that today, only four of the nine concessions are active; the enabling titles for the rest have expired.

Franco Navarro, of the Regional Government of Ucayali, told Mongabay that during flyovers in 2023, up to 21 unauthorised airstrips were detected inside forest concessions and that all the information was sent to the respective concession holders and to the corresponding authorities. These included the Dirandro and the Provincial Prosecutor Specialising in Illicit Drug Trafficking Crimes in Ucayali.

However, a Pucallpa antidrug agent claimed that he had never received any “document from any company with a forest concession that reports an airstrip on those lands.”

While the responsibilities shift from one side to the other, additional airstrips continue to be built.

Of all the airstrips built within forest concessions, five were built between 2020 and 2021, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, forest audits were significantly reduced due to restrictions on field work.

“There are 36 Indigenous leaders [who were] murdered, and this number will increase as long as the underlying problems remain unsolved. This is going to continue,” said Guimaraes of AIDESEP, who cited an even higher number of crimes than the number identified by the CNDDHH.

Part II

The audience erupts into cheers and applause. The emcee has just announced the four finalists of the “Miss Juan Chávez Muquinuy” beauty pageant, who take the stage for their final walk down the runway. The competitors are all schoolgirls between 13 and 15 years old, parading in tops, shorts and platform heels.

It’s 8 pm, and although there’s no electricity in the village, the ceremony venue is lit using solar panels, and music booms through two huge speakers.

“Until three years ago, the winner was decided by the number of raffle tickets sold by each salon. Now we celebrate properly,” the mother of one of the contestants says.

Nearly the whole village is gathered to witness the coronation of a new queen in an Indigenous community of the Kakataibo ethnic group, located in the province of Padre Abad, in the jungle of Peru’s Ucayali region.

The Kakataibo are a warrior people who have historically lived between the regions of Loreto, Ucayali and Huánuco, in a vast territory split in two by the Federico Basadre Highway. In the northern area they live with the Indigenous Shipibo-Conibo people, in the towns of Nuevo Edén, La Cumbre, Muruinia, Santa Rosita de Apua, Santa Rosa, Yamino and Mariscal Cáceres. In the south, they reside in the Native communities of Santa Martha, Puerto Nuevo, Sinchi Roca I, Sinchi Roca II, Unipacuyacu and Puerto Azul.

These groups have a key cultural role, as they form a security cord around the Kakataibo North and South Indigenous Reserve, the forest where Indigenous people live hidden in voluntary isolation and initial contact. However, in recent years, settler groups have invaded their territory, bringing drug trafficking, illicit coca leaf crops and illegal logging to the area.

The arrival of outsiders has changed the social dynamics in some of these Indigenous communities. The new routine is evident in the noisy passage of motorcycles adorned with neon lights, in the use of concrete and bricks in homes that were once made of straw, and in the wads of cash that some visitors carry.

Indigenous leaders like Fernando (not his real name) worry about the transformation of their communities and the loss of ancestral customs.

“Now everything is calamine, cement. The community is not like it used to be. This technology signifies the changes, but we’re afraid of losing our own culture and language,” he said.

A team of Mongabay Latam journalists, guided by the findings of the artificial intelligence algorithm that they developed together with Earth Genome, reached two of the Kakataibo villages located north and south of the reserve. We will not name them for safety reasons. The new neighbours use violence to sustain their illegal activity and establish a drug trafficking route. This instills fear, which was the biggest change found in the village dynamics.

Satellite analysis from the algorithm has detected evidence of the drug trafficking route: hidden runways that have appeared in the middle of the community’s forest land. The village’s fear is not unfounded.

Since the pandemic, 15 Indigenous leaders have been killed in Ucayali, Huánuco and Pasco, six of them Kakataibo, including the leader Mariano Isacama. His body was found on July 14 this year in the district of Padre Abad, in Ucayali, a month after he was reported missing.

Mongabay Latam met Isacama during the production of this report. The community members called him “Peru” as he loved to commentate sporting events, and he was much loved in this area. At least 40 members of the Kakataibo Indigenous Guard set out in search of him, but his body was found with signs of torture three weeks later. The Human Rights and Interculturality Division of the Ucayali Second Prosecutor’s Office is investigating the causes of the crime; Isacama received anonymous threats after condemning the presence of invaders.

Three Overdosed Schoolchildren

An old wooden cabinet displays 2,557 cardboard folders, arranged vertically. These contain the medical records of Indigenous and foreign residents treated in the last ten years at the Kakataibo community’s medical centre. But what happened in 2023 had never been recorded before. Three teenagers between the ages of 14 and 16 arrived at the medical center with tachycardia, dilated pupils, high blood pressure and clear signs of paranoia.

“We don’t have a lab here to test blood samples, but as soon as we saw the kids we knew it was paste,” one of the nursing technicians said, referring to cocaine paste.

The teenagers study at the community school. Two of them are Kakataibo Indigenous people and the third moved with his family from Huánuco. The medical staff injected them with sodium chloride to prevent dehydration and kept them on stretchers until the symptoms passed. None of the medical staff at the centre have been trained to deal with cases of overdose or toxicological emergencies associated with drug use in Indigenous communities, much less in minors.

The locals say it was a group of young people who brought the drug to the village, arriving under the pretence of planting bananas and cassava. As soon as the community found out the truth, they sent them away, but they know that two of them are drug traffickers.

There are several settlers who came to live in this community adjacent to the Kakataibo South Indigenous Reserve, after renting or invading plots to supposedly work as farmers, but the neighbours know they are growing coca leaf crops.

The reserve is also home to peoples who live in isolation.

“The Kakataibo people consider the isolated people as brothers; they want to protect them, but their land has practically been taken over by invaders. … Some plant coca leaf because it generates income. It is a complicated situation, so we try to work on processes that improve their quality of life,” said Miguel Macedo, an anthropologist at the Institute for the Common Good (IBC), an environmental organisation that works in rural areas.

The state’s abandonment of the community is evident in their lack of basic needs. The families don’t have drinking water or Internet, and only some houses have energy from batteries or solar panels. The medical centre that helped the overdosed teenagers had to close down two of its rooms because the roof fell apart, and many folders in the school are in poor condition. However, the community does have huge speakers and sound equipment.

In this area, a quarter of a hectare can produce 313 kilogrammes of coca leaf every three months, when the season has been good; but if farmers have to deal with infestations and fumigations, they may harvest only 188 kg At best, this amount is equivalent to 287 kg of dried leaf that sells for 446 US dollars. This is more than the amount earned for traditional crops, but when divided by month, the 148 dollars of profit does not cover even half of a minimum wage.

The real business lies in the other links of the drug trafficking chain. Producers can obtain 2.14 kg of cocaine paste from one metric tonne of dried leaf, valued at 4,712 Peruvian soles (1,241 dollars). However, when this drug is converted into cocaine hydrochloride, drug traffickers pay almost twice as much, so 2.14 kgs costs 7,802 Peruvian soles (2,054 dollars) in the production areas.

The final profit comes from the sale to the consumer: a single gramme of cocaine is sold for 286 dollars in Saudi Arabia and 30 dollars in the US, according to UNODC data. That is, for 1 metric tonne of processed coca leaf, converted into cocaine hydrochloride and distributed on the streets, organized crime reaps 61.2 million and 6.4 million dollars respectively in these two countries alone.

Narco Flights

One Kakataibo community in the south of the Indigenous Reserve has the longest connection routes for drug trafficking. The usual route to reach this community starts in Pucallpa, the capital of the Ucayali region, and continues toward the city of Aguaytía before transferring to van or raft. However, paths connect this community with the neighbouring region of Huánuco, specifically with the Codo del Pozuzo district and the province of Puerto Inca, which the Anti-Drug Police considers an area used for “planting, processing, storage, transport and shipment of drugs.”

This strategic location has been used by criminal groups to extend their production chain.

“The Kakataibo Indigenous Guard monitors, destroys maceration pits and burns crops, but there are a lot,” said a local source who asked not to be named for safety reasons.

The monitoring of illicit coca crops carried out by the National Commission for Drug-Free Life and Development (DEVIDA) in 2023 confirms that these plantations are present in 1,082 hectares of Kakataibo territory - and 682 of these hectares are within Native communities. However, Fernando says the eradication operations carried out by the state up until then, and the work of its surveillance teams, have served to stop the expansion of these crops.

According to sources from the Anti-Drug Directorate of the National Police (DIRANDRO), the coca leaf from this territory is processed in maceration pits and converted into cocaine paste and then sent mainly to Codo del Pozuzo, in the province of Puerto Inca, in Huánuco. From there, the criminal groups send the shipments in light aircraft heading for Bolivia.

Mongabay Latam identified six hidden airstrips — two inside and four around Indigenous reserves — through the AI search tool developed together with Earth Genome. The programme detects airplane infrastructure hidden in the forests. Each airstrip found was verified with official and local sources, who confirmed they are used to transport drugs.

The Global Forest Watch satellite monitoring platform shows that airstrips were opened in 2015, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2021. Their length ranges from 350-940 metres and four of them are less than half a km from the Santa Ana, Huacapistea and Dorado rivers, a strategic location to expedite the loading of the aircraft, as some interviewed sources mentioned.

The overlap of the illegal crop layer with that of the hidden airstrips confirms that many of these have been built in the middle of coca plantations, and within a radius of at least 2 km, the platform identifies between ten and 26 hectares of these plantations. In total, 37 hectares of coca surround two of these illegal aerodromes.

Sources on the ground, who asked that we omit their names to avoid dangerous repercussions, said they feel trapped by this illegal activity and could no longer trust even the authorities.

“We know where the airstrips are; they’re not very far from where we live, but we don’t go there for safety reasons. … They’re armed, and everything is guarded. They’ve even surrounded them with mines,” one source said.

The head of the Division of Maneuvers Against Illicit Drug Trafficking in Pucallpa, and colonel of the Peruvian National Police, James Tanchiva, says they have identified seven of these illegal airstrips: four in the north and three in the south, and they are already coordinating with the community authorities to destroy them.

Some of these, the colonel says, have been set up in almost inaccessible areas with the consent of community members.

“Drug traffickers pay a certain amount of money to residents or the authorities for using those territories or for using those airstrips. … There are several airstrips that can only be accessed by helicopter. By land we can only reach two or three, no more, but we are waiting for the support of a National Police aircraft to reach the rest,” he said.

To move the illicit cargo to these areas, the criminal groups walk or ride motorcycles along tracks until they reach the nearest river or road. These paths are made by illegal loggers and miners, in a sort of unspoken pact.

“There are many illegal loggers who build roads to enter the communities and cut down wood. There is an agreement between illegal loggers, drug traffickers and illegal miners, so they make roads and use them to transport drugs,” Tanchiva said.

According to the colonel, there are several groups of gatherers who meet to ship the goods to Bolivia and, from there, send them to Colombia or the United States. For this, they send out armed personnel.

“When they’re organising a flight to transport drugs, they inspect the area a day or two earlier. They send people or get people that are already there to check that there is nothing strange. They take all their measurements. The same day, they arrive and move the drugs with their security personnel, who are armed,” he said.

Aerial photographs taken last March by the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle (AIDESEP) and the Native Federation of Kakataibo Communities (FENACOKA) confirm two of the illegal airstrips detected by the search tool used by Mongabay Latam. These are located in an area that the Kakataibo Indigenous communities have reclaimed as their own since 1991.

The people live on some 3,800 hectares, a very small area compared with other Native communities, while the Regional Directorates of Agriculture of Ucayali and Huánuco do not approve their request to expand their territory. On the contrary, the state approved logging licenses in the very area of their requested expansion.

The invaders have taken advantage of this dispute, devastating the forests for cattle pastures and, once again, drug trafficking. DEVIDA’s map confirms that illegal crops have taken over the expansion area requested by one of the Indigenous communities, especially in the section in Huánuco bordering the Kakataibo South Indigenous Reserve.

For community leaders, this territory is already lost.

“We will no longer claim that land because it’s been invaded by people who have deforested to keep livestock and grow coca leaf. What we’ll continue to demand is the expansion of land in Ucayali, where there are logging licenses,” Fernando said.

Fight or Live With the Enemy

In the surrounding area of the Kakataibo North Indigenous Reserve, across the Federico Basadre Highway, there is another Native community of Ucayali that is being threatened by drug trafficking and deforestation. Mongabay Latam visited this community, after following paths through destroyed forests, which have been replaced by oil palm and cattle pastures.

This area, located in the district of Padre Abad, faces similar problems to the Kakataibo peoples: the illegal crops infiltrating their territories. It is not difficult to find coca crops drying in the sun. The difference is the lack of roads accessible from the highway, which prevents members of the drug chain from settling there.

Furthermore, in some communities in the north, the Kakataibo Indigenous Guard ranges through the forests to find new areas of deforestation and monitor the expansion of illegal activity. This consists of groups of about 25 men who enter the jungle every 15 days with machetes and food. During their rounds, they mark the coordinates where they find new areas felled or sown with illicit crops and coordinate with the police to eradicate them. They even burn the maceration pits they discover along the way.

The president of one of the Indigenous Guards said that fewer and fewer people were renting land in Kakataibo North, due to their awareness work and because the Guard members receive a monthly payment, allowing them to afford basic provisions.

“The biggest problem now is on the border between two Indigenous communities because they’ve identified large areas of coca crops there. Also there is a hamlet where there are plantations and maceration pits,” one of the Indigenous Guard members said.

According to the community members, drugs produced in this hamlet are transported to a Native community located in Kakataibo Norte, where the algorithm detected an illegal runway.

The leader of one of the Kakataibo North communities agrees that the current threat is illegal drug laboratories.

“There are labs in the hamlets. [The managers] don’t carry their products through here because they go by river and adjoining roads, where there is no surveillance,” he said. “No more primary forest is being opened for growing crops; now they’re only being grown in existing secondary forests, which is why deforestation is also decreasing.”

Faced with these threats, the Kakataibo communities have assumed the role of defending and conserving their territories, which is costing the lives of their leaders.

“Illegal crops are well-established in both communities, and the government is not doing anything. So we’ll just keep dying,” said Herlin Odicio, a Kakataibo leader and vice president of the AIDESEP Ucayali Regional Organization. “We need to combat these dangerous groups that are turning our territories into no-man’s-land. We’re going to have to apply Indigenous justice to protect ourselves, we have no choice.”

Part III

The hum of a small plane is heard overhead during a community assembly, but no one looks up. Conversation rises naturally over the sound as the engine’s intense roar fades into the background. The aircraft takes five minutes to pass over an Indigenous community located between the districts of Yuyapichis and Puerto Bermúdez, its course traceable by simply following the sound; the plane is hidden from view by clouds.

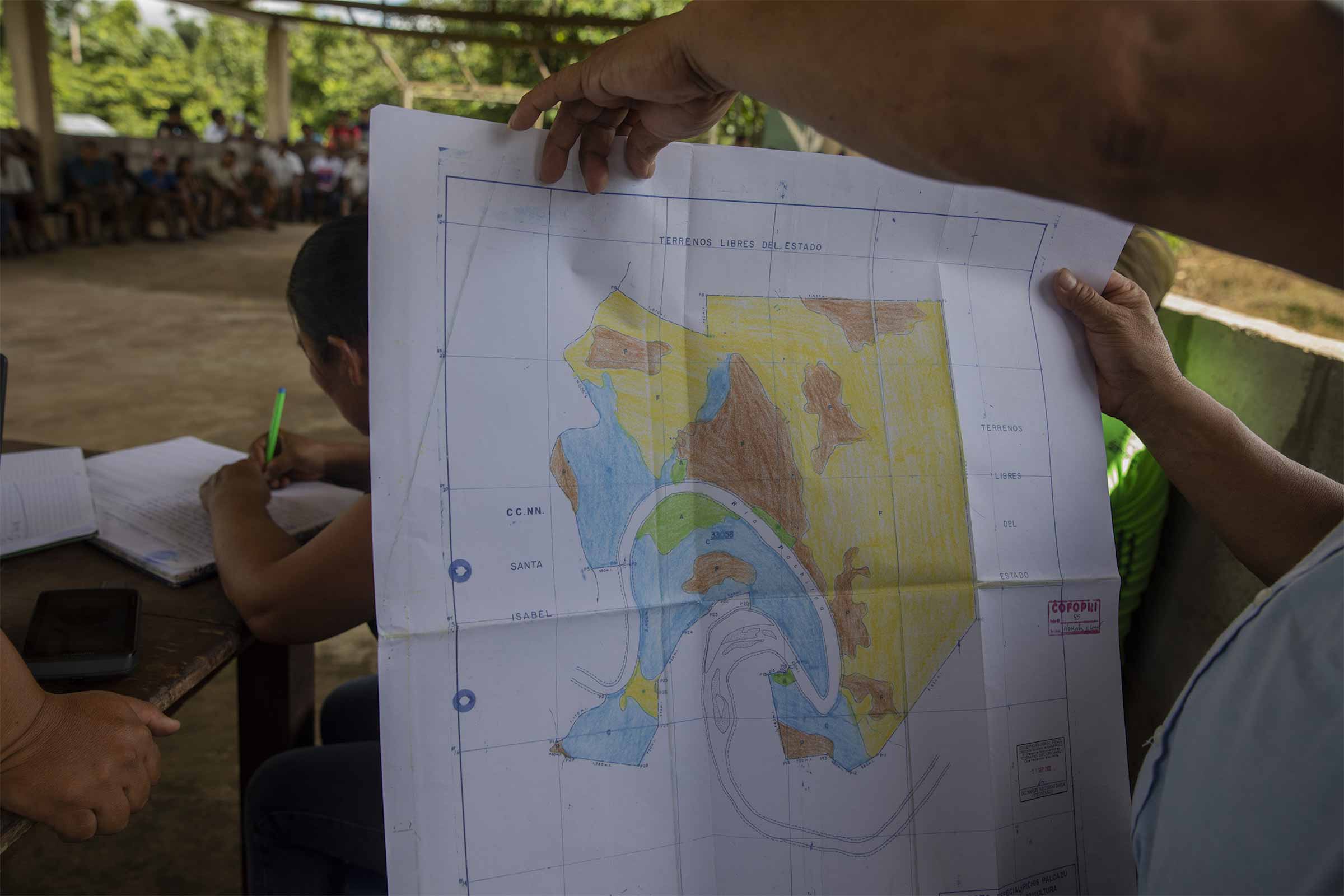

On the morning of Sunday, April 21, 2024, this Yanesha community, nestled between the regions of Huánuco and Pasco in Peru’s central rainforests, is hosting a gathering of Indigenous residents from Huánuco and its two annexes. Some have arrived by boat, navigating up the Pachitea River, which forms at the confluence of the Pichis and the Palcazu rivers. At least 200 people are present, focused on discussing one central concern: securing legal titles for their lands. Nothing else can distract them today — not the sound of the small plane, nor the clandestine airstrips surrounding the community that daily serve drug trafficking.

“Didn’t you hear what was happening earlier? That’s them. I don’t know where they are going,” a local source told us in hushed tones, confirming the aircraft’s departure.

“From here, whatever they take with them will go to other areas of Yuyapichis. That’s where they fly,” he continued. “It used to be more regular, busier. There was even a bit of money in it; it was fun back then. But now it’s different. [It changed] when they started eradicating coca.”

Satellite images reveal that both the airstrips and illegal crops are still there. This suggests that either coca eradication efforts failed to reach the area, or its replanting has simply reclaimed the space. For a year, Mongabay Latam scoured the dense forest surrounding the community, looking for airstrips that can measure 500-1,000 metres which can appear suddenly in just a few days. With the help of a search tool developed with AI, our team of journalists detected eight inside the territories of two Yanesha communities and seven around them.

The two communities, both belonging to the Yanesha people, share a rich history and are connected by a single entrance road leading to the Fernando Belaúnde Terry Highway, also known as Marginal de la Selva. Positioned on the banks of the Pachitea River, their territory spans the regions of Huánuco and Pasco and falls within the Oxapampa-Asháninka-Yanesha Biosphere Reserve. But another bond links them: a network of organised crime operating within this spectacular landscape.

Drug traffickers control the landing and take-off zones for narcotics shipments, forming a geographic triangle where nine districts across three provinces — Huánuco, Pasco and Ucayali — converge in the central rainforest.

Living in Fear

“If we talk about them and say that drug trafficking happens here, they will find out and then — bam! —they will take you down. They are lawless,” said a source on the ground, who requested anonymity for safety reasons.

In these communities, they do not talk about drug trafficking. It is a forbidden term that arouses a sense of distrust and fear. Those who live here are survivors of the internal armed conflict between the state and the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), which raged throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.

“They would come and hold meetings, carrying weapons. … I was between 15 and 20 years old. That was our reality. We had to obey their laws, otherwise they would kill us. They made us walk around with weapons, instilling fear of death,” one of the Indigenous leaders said, reflecting on a time when terrorist groups controlled Peru’s central rainforest.

His words reflect the scars left by the years of violence against the Yanesha people. Their story is documented in the final report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It tells how, between 1982 and 2000, the Shining Path and the MRTA swept through the regions of Junín, Pasco and Huánuco, seizing control of towns and Indigenous communities. Fighting, assassinations, forced displacements and kidnappings that plagued the Indigenous population during this time are recounted in the section detailing the scenes of violence.

Perhaps that is why residents avoid discussing the internal armed conflict, unless someone else brings it up. One of the oldest inhabitants of the local community, whom we will refer to as Antonio to protect his identity, offers another explanation for the violence experienced by the communities of Pasco and Huánuco: the rise of coca cultivation.

“They [the subversives] said that in order to survive, we all had to grow coca leaf,” he recalled, referring to the period when regional forests began to be overrun with illegal crops.

A report published in 2004 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime wrote of coca cultivation taking place in the area from 1986, when displaced coca growers from Alto Huallaga arrived.

“In the early 1990s, coca cultivation in this region reached up to 12,000 ha for a production of coca leaves oriented towards cocaine production,” says the report, which also describes a subsequent decline in cultivation in the mid-1990s due to falling prices.

Almost 20 years later, the report Peru, Coca Cultivation Monitoring 2023 revealed that the area had reemerged as “the fifth largest production zone in terms of area under coca bush cultivation, accounting for 4.6 per cent of the national total with an area of 4,266 hectares”.

The section of the central rainforest referred to in the UN report includes the subbasins of the Pichis, Palcazu and Santa Isabel rivers, as well as part of the Pachitea River, where the communities in this investigation are located, along with the 15 clandestine airstrips detected by Mongabay Latam.

Antonio explains that the coca fields are located farther away from the community, on land occupied by settlers, at least three hours away.

“We don’t dare go there because there are risks,” he said. “That’s where the drug traffickers are.”

Violence has not left the area either. According to Peru’s National Human Rights Coordinator and ORAU, the Ucayali Regional Organisation of AIDESEP, the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest, 11 people, including Indigenous leaders and community members, were killed in the regions of Huánuco and Pasco between 2020 and 2024 alone. That number rises to 15 when the Ucayali region is taken into account. The threat of terrorism has simply been replaced with a threat of aggression from drug traffickers.

The Drug Trafficking Triangle

Both the Yanesha communities have clandestine runways — five in one community’s territory and three in the other. Satellite images confirm that these airstrips began to appear between 2015 and 2016, and that the latest one was constructed in February 2023. Each lies on one side of the Pachitea River, some just meters away, and others less than 2 kilometres from its banks.

Both communities are also just a 30-minute drive from Ciudad Constitución, the capital of the eponymous district in the province of Oxapampa, Pasco. Ciudad Constitución is the economic and commercial centre for those living in and around this part of the central rainforest — but it is also a hub for drug trafficking.

“All the ills caused by drug trafficking can be seen in Ciudad Constitución. Violence, extortion, murders — all are part of a chain of problems directly tied to illegal activities in the area,” said Florencio Santiago Carrillo, an executive with Peru’s National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA), based out of the La Merced zonal office in Ciudad Constitución.

The district of Constitución, home to around 15,000 people from the Indigenous Yanesha and Asháninka peoples, as well as Andean migrants, includes a small city centre roughly ten blocks long, cut through by the Fernando Belaúnde Terry Highway. The surrounding rural area is, however, much larger.

Santiago notes that at least 20 killings were reported in the city in 2023, most of them related to drug trafficking.

“The police presence is limited when it comes to dealing with the logistics of drug trafficking in the district,” he explained.

Constitución sits at the border of the Huánuco and Pasco regions and is directly connected to Ucayali via the Fernando Belaúnde Terry Highway, just like the Yanesha communities. Surrounding the city, three regions converge to form a geographic triangle that facilitates drug trafficking by air, land and river.

On the Huánuco side, the province of Puerto Inca includes the districts of Honoria, Tournavista, Puerto Inca, Codo del Pozuzo and Yuyapichis, forming a hub for drug trafficking. On the Pasco side, the province of Oxapampa encompasses the districts of Constitución and Puerto Bermúdez. To the east, it connects with the province of Padre Abad in Ucayali, which, on a larger scale, includes the provinces of Coronel Portillo and Atalaya. Together, these regions create a route that significantly facilitates drug trafficking in Peru’s central rainforest.

The most vivid symbol of the drug traffickers’ presence in the region is an abandoned light aircraft that lies beside the Fernando Belaúnde Terry Highway. For those arriving from Pucallpa, its rusty hulk is visible from the bridge over the Palcazu River, at the entrance to Ciudad Constitución.

The streets of Ciudad Constitución itself reveal striking contrasts. Large hotels stand on unpaved lots, while vibrant nightlife attracts underage youths speeding through town on their flashy motorcycles. On the return trip to Pucallpa, our driver speaks openly about how drug trafficking fuels the economy in Ciudad Constitución and, more broadly, throughout this entire geographic triangle where drug trafficking has deeply taken root.

In the last week of April, a contingent from Pucallpa’s Anti-Drug Directorate (Ucayali) arrived in Ciudad Constitución for a targeted operation against drug trafficking.

“We managed to destroy four airstrips and two rudimentary cocaine production labs,” reported James Tanchiva, head of the Division of Maneuvers Against Illicit Drug Trafficking in Pucallpa. “Constitución has been a coca-growing area for many years due to the high production of coca leaves. And wherever there is coca leaf production, there are labs for manufacturing cocaine and cocaine paste.”

According to DEVIDA’s latest coca cultivation report, three of the nine districts that form part of this production zone — Puerto Inca, Yuyapichis and Constitución — account for 63.8 per cent of the total coca cultivation area. The Pichis-Palcazu-Pachitea area also ranks third in terms of drug seizures by the Peruvian Police between October 2020 and October 2022, according to the Study on Cocaine Dynamics in Peru report by DEVIDA and UNODC.

These findings are key to understanding why 15 of the 76 illegal airstrips identified by Mongabay Latam in the whole Peruvian Amazon are found between Huánuco and Pasco.

Patricia Talavera, a socioenvironmental specialist at the Institute for the Common Good (IBC), agrees that Constitución’s economy is largely driven by the drug trade. But she said she believes this extends beyond this city, explaining how corridors dominated by illegal economies have formed along both banks of the Pachitea River.

“We have three predominant illicit activities,” she explained — illegal mining as well as drug and timber trafficking.

The first corridor is made up of the districts of Puerto Bermúdez and Constitución, in Pasco, and Puerto Inca and Tournavista, in Huánuco. This area, Talavera explains, is dominated by “a drug trafficking network linked to illegal mining — two illicit economies that go hand in hand”.

The second corridor runs through the districts of Padre Abad and San Alejandro, in Ucayali, to Codo del Pozuzo, in Huánuco. Here, she added, “a drug trafficking network related to illegal logging” has taken hold. In both cases, drug trafficking is deeply intertwined with other illegal economies.

Drug Trafficking Routes

Tanchiva confirms that this region serves as a transport route for drugs and explains that “many narcotics produced in the VRAEM [a term used to refer to the Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro River Valley] are moved to these areas to be transported by air. The route extends through Oxapampa, Codo del Pozuzo, Ciudad Constitución and also to Atalaya.”

In 2023 alone, 70 clandestine runways were destroyed in Ucayali as part of an operation known as Troya, according to Colonel Tanchiva. The Ucayali’s Anti-Drug Directorate jurisdiction encompasses the regions of Huánuco, Pasco and Ucayali. So far in 2024, Tanchiva says, five airstrips have already been destroyed, with projections for the year matching or exceeding last year’s totals.

The anti-narcotics unit (DIRANDRO) in Ciudad Constitución explains that the drugs are transported in planes taking off from clandestine airstrips in areas surrounding the city. Boats carry the cargo up the river to a point near the runway, after which it is moved on foot with the help of people hired for that purpose.

When one of these airstrips is destroyed, it is often rebuilt within a week. “Drug trafficking organizations have efficient logistics,” Tanchiva tells us. “They have an armed wing, and they have money. That is the reality.”

Images from Mongabay Latam’s satellite monitoring show a profoundly altered landscape; dense jungle punctured with small deforested patches, pits scattered across the forest and a river running along the area’s edge. Notably, 11 of the airstrips found between Huánuco and Pasco are located within illegal coca fields, with another five just a few meters away. Coca cultivation around these runways spans 159 hectares (3within a two km radius, an area about 222 times the size of Peru’s National Stadium.

The Pachitea River may seem calm from the surface, but police reports and satellite images reveal a different story hidden within the dense forest along its banks. Here, illegal coca crops are growing, cocaine paste and cocaine hydrochloride production laboratories are being established and clandestine airstrips are being opened to transport drugs produced locally as well as shipments from other valleys, primarily from the VRAEM.

Flights to Bolivia

Where do the light aircrafts from Peru’s central rainforest go? According to DIRANDRO, their primary destination is Bolivia.

“Planes coming from Bolivia reach here in around five hours,” said an official from Ciudad Constitución.

Ricardo Soberón, former executive president of DEVIDA, explained that the Bolivian departments of Beni and Santa Cruz — regions typically focused on cattle ranching and agriculture — have more than 200 airstrips. Light aircraft, used for transporting cattle and spraying soybean crops, are common here.

“Any cattle ranch in Beni needs a light aircraft and an airstrip. Secondhand aircraft can be bought for $50,000 in Florida,” Soberón said. “While these planes serve local needs, the drug trafficking economy exploits this infrastructure.”

Ucayali has become a hub for drug trafficking and other illicit economies in recent years, he continued, due to its “strategic” location, with good land, river and air connections.

An example of this connectivity is the Fernando Belaúnde Terry Highway, which links Pucallpa, the capital of Ucayali, with Ciudad Constitución in just three hours, crossing the rainforests of Huánuco, Pasco and Junín.

The Pachitea River, which flows into the Ucayali, further connects these regions.

“Drugs are moved by river, land and air. A small plane can carry 500-800 kg; by river, up to 100 kg and by land, smaller amounts, typically divided into 100 kg loads transported in convoys of five to ten people, each taking different routes,” Soberón said.

Tanchiva explained that the presence of the Joint Command of the Armed Forces and Police in the VRAEM was “creating a balloon effect. Since they can’t operate from there, traffickers are shifting their drug shipments to other areas with clandestine airstrips, particularly to Constitución”.

For almost five years, six districts across Huánuco and Pasco were under a state of emergency: Puerto Inca, Tournavista, Yuyapichis and Codo del Pozuzo in Huánuco’s Puerto Inca province, along with Constitución and Puerto Bermúdez in Pasco’s Oxapampa province.

Supreme decrees issued between March 2019 and December 2023 ordered authorities to “strengthen the frontline fight against organised crime related to illicit drug trafficking and associated offenses.” The final extension of this state of emergency ended in February 2024.

Cacao as an Alternative

In the two Yanesha communities, residents are working to counter the illegal trade by growing cacao as well as reforesting and cultivating other crops. This year, rising cacao prices, which reached nearly 40 soles (10.50 dollar) per kg in April, gave hope to those who had been growing the crop for several years, though by July prices had dropped to between 25 and 30 soles (6.60-8 dollars). Still, current cacao prices remain significantly higher than in previous years, largely due to a drop in production in Africa, which was hit by severe droughts.

The Native communities also grow achiote and yucca in their fields and raise cattle. The Federation of Native Yanesha Communities (FECONAYA) is committed to supporting projects that improve living conditions, with a focus on cacao farming and livestock.

“We are working with agricultural engineers to provide technical advice on cacao cultivation, livestock management and reforestation programs,” said FECONAYA president Jaime Chihuanco.

During community assemblies held while Mongabay Latam visited the two communities, residents consistently called for improvements to health posts, school infrastructure, water systems, connectivity and communication services.

“Our community has suffered for years over land issues and has been completely neglected,” complained one speaker. “To the state, we practically do not exist — it is a form of marginalisation. We have more than 100 children studying at this school, and each year, parents work tirelessly to extend the classrooms by a single meter so their children can have a place to learn.”

Residents in the other Yanesha community echo these concerns. When times are good, villagers invest in infrastructure to improve their quality of life. They managed to install a drinking water system by constructing a well, but their school classrooms have not seen similar improvements.

Such shortcomings are visible in both communities; in one, children must study in classrooms resembling wooden boxes, while in the other, the health post has no permanent staff.

Yet, the primary concern centres on a single issue: titling. At the community assembly on April 21, 2024, residents discussed their options for moving forward with land title updates and formal registration with the National Superintendency of Public Registries (SUNARP).

The territory’s location across two districts, two provinces and two regions, Huánuco and Pasco, has created ongoing challenges in defining its legal security. Compounding this issue is the fact that regional governments have issued property titles to foreigners — colonists — who have encroached on Indigenous lands and established settlements.

“If the process for updating the community’s territorial boundaries isn’t expedited, they will continue to lose land,” warned Michael Mercedes, head of the Native Communities Office at the Puerto Bermudez branch of the Pasco Regional Directorate of Agriculture.

One of the communities received official recognition in 1981 and was granted its title in 1986; however, it has yet to be inscribed in the public registry. The other community was also recognized in 1981 and titled a year later in 1982. Unfortunately, these titles only include geographic references for its boundaries and still require a georeferencing process to meet current regulations.

Chihuanco, president of FECONAYA, expresses concern that the lack of legal security hinders communities from accessing government funding for agricultural and reforestation projects.

The evening draws in as we glide down the Pachitea River, surrounded by the lush expanse of dense forest lining the shore. Many of the community members’ plots are nestled among the trees, Antonio tells us, along with areas dedicated to reforestation.

We arrive at a bend in the river, get off and walk through a field with several tree species. Antonio identifies them: sangre de grado, cedar, lemon trees. This space, once home to coca cultivation, is now dedicated to reforestation. A parrot flits overhead as we pass a house in the middle of the land; its owners are attending a community assembly. Cows and bulls graze nearby, oblivious to our presence. In this serene moment, the landscape resembles an oil painting, seemingly untouched by the drug trafficking that looms just miles away.

The boat comes to a halt, shuddering against the dirt bank that rises from the edge of the Ucayali River. Sixto, tanned and with a frown cutting deep furrows across his forehead, jumps ashore. He strides up to a flat area dotted with banana plantations, yucca crops and scattered foliage. He raises his hand and waves.

He then follows a path that penetrates a wall of trees, passes through mudflats and traces the undergrowth that thickens the forest. He doesn’t speak. He knows where to go, and that’s all that’s needed. At intervals he says, barely whispering, “It won’t be long now.”

During each stretch, as he keeps up his pace, Sixto scans the horizon, although it’s always the same scene of trees and scattered green. The dense jungle he passes through lies in Tahuanía district, Atalaya province, in the Peruvian Amazon. Thirty-four minutes into this trek along this tangled route, the roof formed by the treetops suddenly opens up to reveal a huge rectangle of bare earth.

“It is 985 metres, a big ‘cancha’ [field],” he whispered, pointing to the other end. “We’ve arrived.”

No drug planes have taken off yet from this clandestine airstrip. This stretch was prepared five years ago, but with the COVID-19 outbreak, there was no need for traffickers to find new ways to get their drug shipments out, Sixto recalls, now less tense, more talkative. He was one of the young men who prepared the land after it was cleared. He says he was called by a relative, did the job for two weeks, then returned home. Sixto isn’t his real name; in the face of danger, he prefers to remain anonymous.

The airstrip has been abandoned since the onset of the pandemic. However, groups of men have begun to revive it for use again.

“They come every so often, leveling the land and pruning the thicket that has grown on the sides,” a local source said. The fear that was haunting Sixto on the way here was the uncertainty of not having accurately calculated whether we were going to find the area cleared. It becomes evident that this is a drug trafficking zone in preparation, located close to the Indigenous communities of Chanchamayo and Pandishari. The area that Sixto shows us is just one of the dozens of clandestine airstrips that have turned Atalaya into the province most blighted by drug trafficking flights in Peru’s Ucayali department.

Using satellite imagery and artificial intelligence, Mongabay Latam and Earth Genome have detected 45 clandestine runways for outbound drug shipments in Ucayali, of which 18 are within Indigenous territories and 19 close by.

Hidden Forest Sites

The airstrips identified by the algorithm and AI can also be viewed on the Global Forest Watch satellite monitoring platform. The information obtained through the satellites was cross-checked with findings from the Peruvian police’s antinarcotics unit, DIRANDRO, and the Ucayali departmental agency for forest and wildlife monitoring, or GERFFS.

The development of this process, together with verifying each airstrip with local and official sources, allowed us to confirm that there are at least 45 runways used for drug trafficking in Ucayali. Of these, 31 are dispersed among the four districts of Atalaya province: 17 in Raymondi, six in Sepahua, and four each in Yurúa and Tahuanía. Concerningly, 26 of the 31 illegal airstrips in Atalaya affect Indigenous communities and reserves located in the province.

In the case of Tahuanía, the police’s antinarcotics tactical division DIVMCTID in Pucallpa, the Ucayali departmental capital, says the clandestine airstrips are abandoned.

“But if there are criminal firms or organisations with shipments ready that require the use of a runway that is currently inactive, then they clean it up well and activate it immediately,” the agent in charge told Mongabay.

Five years ago, this route was implemented for the arrival and departure of drug planes in the Tahuanía forest. Video by Mongabay Latam.

That’s what’s happening at the airstrip we visit with Sixto. The bushes, which are cut back on the sides, reveal that the airstrip was initially 5 m wide. There are discarded rakes and cylinders, which serve as markers where sections of land have already been worked. Everything, it seems, is being prepared for the next drug deliveries.

Police report that Cessna aircraft sporting the Bolivian flag land in Atalaya to pick up shipments of 300-350 kilograms of cocaine hydrochloride. One of the main destinations for the drugs is northern Bolivia’s Beni department; sometimes, after a layover here, the same plane then continues on to Brazil.

Sources in the area say there’s a business of renting out the runways in this part of the Amazon. If someone needs to use one, a source explains, they can choose the most convenient place and pay between 10,000 and 20,000 dollars. Although the source doesn’t admit it, it’s clear that his experience in the region has made him knowledgeable of the details involved in sending drug shipments abroad.

“Up to four flights can take off a day,” he said. “Sometimes while one plane is loading the drugs, another is departing. Each operation must take five minutes, at the most. In this way, a single organisation can transport up to 1,200 kg of cocaine a day.”

It’s 2 pm and, according to what we’ve heard, all the flights scheduled for the day of our visit have already taken off.

“The planes leave between 6 am and 9 am, and it is very rare for an organisation to use the same cancha more than twice. They are always looking for new runways to land on and depart from,” a source told us.

The Asháninka, Ashéninka, Yine and Shipibo communities of Atalaya are the most affected by drug trafficking. Related crimes - threats, extortion, contract killings - have driven Ucayali into the unenviable position of one of the most dangerous departments for Indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon.

ORAU, the Ucayali chapter of the Indigenous umbrella association AIDESEP, has since 2013 recorded at least 35 killings of Indigenous leaders in Peru. Herlin Odicio, ORAU’s vice president, estimates that at least ten of these killings occurred in Ucayali. ORAU, which brings together 13 federations of various Indigenous peoples in Ucayali, has also recorded 28 instances of environmental advocates in the region who have been subjected to death threats or harassment for protecting their territory.

The most recent case was that of Mariano Isacama Feliciano, leader of the Puerto Azul native community, who disappeared on June 21 this year after receiving a series of threats on his cellphone. He was found dead 23 days later, in an open field.

Odicio says he’s convinced it was a revenge killing by drug traffickers.

“Since April, the Indigenous Guard has burned coca fields, destroyed maceration ponds and promoted flyovers [of areas with drug activity],” he continued. “I received information that they were going to retaliate against the leaders.”

In 2023, Ucayali saw 27,340 hectares of deforestation. In the first two months of 2024, it lost 673 hectares of forest, of which 203 were inside Indigenous areas, according to GERFFS, the departmental forest monitoring agency. Agency head Franz Tang told Mongabay Latam that, on average, 45 per cent of the annual deforestation in Ucayali is related to drug trafficking, which coincides with the more than 12,000 hectares of coca crops identified in Ucayali in the latest review by the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA).

“We’re at risk, but the state is not helping us, it does not provide us with security,” said the head of an Indigenous federation, asking to use the pseudonym Francisco because of threats to his life. “We land advocates die because we fight when our rights are violated. Atalaya is becoming a second VRAEM,” he continued, referring to the Valley of the Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro Rivers, Peru’s main narco hub.

Francisco says there’s no doubt that coca plantations, airstrips and drug trafficking operations have increased significantly in Atalaya since 2015. So have the killings and disappearances that, he says, aren’t always known but plague both the province and its Indigenous communities.

“I know of two Indigenous brothers who were murdered in 2023, and one who disappeared this year, he said.

“In Tahuanía, to cite one case, brothers who have been recruited to work for the drug trafficking industry die. We do not really know how many die each day. There are no police officers, no authorities. The state has forgotten us.”

In 2015, the year in which, according to Francisco, drug trafficking began to intensify in Atalaya, the Peruvian government was two years into a series of operations against drug trafficking in various critical areas of the VRAEM. To date, that region still has the largest area of coca crops in Peru, at 38,253 hectares, where drug gangs have carved out inhospitable routes to transfer their product.

Reports from authorities involved in the VRAEM raids in 2015 indicated that between three and four clandestine airstrips were being destroyed daily in the area. In all, around 200 airstrips were disabled. The police’s antinarcotics tactical division in Pucallpa told Mongabay Latam that airstrips then began sprouting up in places like Ciudad Constitución (Pasco department), Codo del Pozuzo (Huánuco), and, later, Atalaya in Ucayali.

“Here they entered Raymondi with force, as well as the area surrounding the Inuya River, in Sepahua,” said a spokesman.

It hasn’t been used yet, but this clandestine airstrip is already being prepared for future drug trafficking flights from Tahuanía. Video by Mongabay Latam.

It’s not only the clandestine airstrips that have moved to Ucayali. In its most recent report, DEVIDA, the national antinarcotics commission, notes that although the VRAEM region accounts for two-fifths of Peru’s total coca-growing area, Ucayali has more coca land in proportion to its total size. Within the department, the so-called Bajo Ucayali area, made up of the districts of Iparía (in Coronel Portillo province) and Tahuanía, Raymondi and Sepahua (all in Atalaya), has 3,355 hectares of coca farms. Trends in VRAEM and Bajo Ucayali, according to DEVIDA’s reports, point to an expansion of illicit crop cultivation — and all the consequences that come with it.

The links between VRAEM and Atalaya area also confirmed by the antinarcotics police in Pucallpa. Officials have identified an important drug route that starts in VRAEM: it begins at the Apurimac River, then joins the Mantaro River and continues along the Ene.

Once the Ene and Perené rivers join, the route follows the Tambo River, which meets the Urubamba to form the Ucayali River in the town of Atalaya. In this way, the shipments arrive in overcrowded boats to the areas surrounding the clandestine airstrips. In fact, 10 of the airstrips detected by the algorithm are less than 2 km from the Urubamba and Ucayali rivers. Military intelligence personnel told Mongabay Latam that 90 per cent of the drugs produced in VRAEM leave Peru by air, with the rest going by road, river or sea.

“But that does not mean that there is no processing in Ucayali,” said Francisco, the Indigenous leader. “Iparía and Masisea [districts] have become production zones, as have some parts of Atalaya. There are Indigenous brothers and sisters who are employed to harvest coca. Often that ends up being the only profitable economic activity here. We have no opportunities because of the lack of interest from the state.”

Reciting almost as if from memory, Francisco points to the Indigenous communities of Centro Lagarto Juvenil, Flor de Mayo, Nueva Claridad de Bambú, Puerto Alegre, Colpa, Flor de Shengari, Chanchamayo, Diobamba, Pandishari, Puerto Esperanza and Galilea are those in Atalaya province alone that are most affected by the drug trafficking operations. Among these, Centro Lagarto Juvenil in Raymondi district, is the most at risk because of the constant arrival of non-Indigenous invaders who have set up coca farms and even a clandestine airstrip there.

The onslaught of drug trafficking in Atalaya has forced several Indigenous communities to undertake risky head-on battles with the criminal gangs, leading to success in some cases. However, the tension has tainted the routines of its inhabitants. This is what’s happening in one of the Ashéninka communities in Raymondi district. There, criminal organizations established a stronghold for drug shipments, which the community and authorities managed to eradicate in a coordinated effort. However, the possibility of the unrest returning remains latent.

There were drug trafficking trails on our land,” a local source, in a clear state of distress, told Mongabay Latam. “We had to form a self-defence committee and informed the Navy of what was happening. That’s how we managed to get them to leave. But now they are trying to use the airstrips for flights again. We don’t want any more problems.”

According to DEVIDA, coca cultivation across Peru amounts to 92,784 hectares of which 14 per cent or 13,054 hectares occurs on Indigenous lands. This trend, too, is increasing, according to the antinarcotics commission.

The dire situation described by Indigenous community members, along with the satellite data reviewed by Mongabay Latam and other organisations that have investigated the issue, contrast with the information provided by Ucayali antinarcotics prosecutors, based in Pucallpa.

The prosecutor’s office told Mongabay Latam that there were only three cases of coca cultivation in Atalaya province but that these had already been “archived,” leaving just one case to date affecting an Indigenous community in Tahuanía. The office also disputed the presence of clandestine airstrips in Indigenous communities in Atalaya.

“The few that exist are in populated centres,” a prosecutor said.

However, the antinarcotics police, DIRANDRO, confirmed in response to a request for information that 58 airstrips in Ucayali had been destroyed between 2013 and 2022. It also reported the destruction of three aircraft in 2012 and 2021, and the crash of four aircraft between 2020 and 2022. Mongabay Latam reviewed all the press releases published by DIRANDRO on operations carried out in Ucayali between 2020 and 2024. We found 132 operations, comprising drug confiscations (40), chemical seizures (12), laboratory raids (51), and airstrip destructions (10).

Drug Trafficking

Before anchoring the boat on the banks of the river in Bolognesi, capital of Tahuanía district in Atalaya province, Fabio outlines on a piece of paper the course we must now take by motorbike. The information he has about the area is that the criminal network based there is on alert due to a recent raid by the antinarcotics police. As a result, a shipment wasn’t exported, the eventual cost of which could be in the millions, as the packages remain only steps away from a clandestine runway.

Cocaine prices jump wildly between one point and the next along the supply chain, peaking at the final destination. An antinarcotics police estimate, cited in a DEVIDA presentation, puts the price of a kilo of cocaine at 1,200 dollars at the production site. This then rises to around 2,500 dollars when it reaches an airstrip for transportation. By the time it reaches the United States, one of the main markets, that same kilo of coke now costs 30,000 dollars; in Europe, the other major consumer market, it’s 60,000 dollars.

“We talk about those costs a lot around here when there are large shipments,” Fabio said before jumping off the boat.

We ride along the highway from Bolognesi to Breu, capital of Atalaya’s Yurúa district, which sits on Peru’s border with Brazil. Fifty minutes into the ride, a turnoff near the border, indiscernible through the undergrowth, marks the beginning of a path that leads to the Indigenous community of Colpa. Another hour’s drive later, this same road, uneven and neglected, becomes an airstrip that travels along the length of the land that corresponds to Colpa: it passes right by the houses of the community’s Indigenous Asháninka people.

“When an aircraft is about to land to be loaded with drugs, all traffic comes to a standstill. So does the population,” said an Indigenous leader who left the community for security reasons. “It doesn’t happen very often, but that’s how we live.”

Our plan is to cross the runway in Colpa and then embark on a hike deep into the forest, to another airstrip inside a logging concession held by the company Ucayali Wood. It’s a similar journey to the one that Sixto led us on near the Indigenous community of Chanchamayo.

But less than 4 km from the first point, we arrive at a log bridge that’s been destroyed, meaning we can’t advance with motorbikes and any other vehicles. Plastic-lined drums full of chemicals and fuel litter the vegetation nearby, as through hurriedly concealed during an urgent escape. As he rides his motorbike, Fabio confirms the information he had and warns that the area is teeming with activity.

“There must be a production centre very close to the runway,” he said. “They have knocked down the bridge so nobody gets close. They are retreating.”

Fabio looks down at what appear to be the tracks of a pickup truck on the muddy ground, and, almost reflexively, an expression of alarm forms on his face.

“At any moment the truck is going to come back and take this away. It’s very dangerous to stay.”