Ukraine: Return to Hostomel

The human story behind just one atrocity in the Kyiv suburbs.

Ukraine: Return to Hostomel

The human story behind just one atrocity in the Kyiv suburbs.

The first time I came to the house at Svyato-Pokrovska in Hostomel, it was because of a police radio call alerting us to two decaying corpses in a yard.

This was in the early days of April, after the Russian withdrawal, and such things were common.

We arrived to observe sappers inspect the bodies, partially concealed by fern trees, for booby traps. The home was well-appointed. Not rich, not overdone, but a house of some means, including a Lexus sedan in the drive.

The extreme violence – head wounds, possible torture, hands bound with wire – and the damage to the property throughout were so discordant with the pleasant suburban scene. Next to the bodies lay a slain terrier.

We could not confirm the dead men’s identities. But clearly a family’s life had been overturned. Quoting one of the policemen, we called the story “Just Another War Crime”.

Two weeks later, IWPR received an email from Anastasia Suslova, a 21-year-old language student. It was her family’s house. In fact, it was not one family’s life that had been overturned, but two. The bodies were the neighbours. Anastasia’s father had been killed elsewhere.

Bucha saw extremities of individual cruelty, while Irpin and Borodyanka suffered devastating bombardment. Of the occupied Kyiv suburbs, Hostomel endured perhaps the fiercest street-by-street battles, as it see-sawed between Ukrainian and Russian control.

The airfield at Hostomel was a critical military objective, potentially providing an air bridge to the capital, a half hour’s drive. Free to transport men and arms, the plan to topple the Ukrainian government within days may have succeeded.

Hostomel ultimately fell, but the efforts of Ukrainian forces – to resist and then render the airfield unusable – slowed the enemy advance and allowed Ukraine time to assemble its defence of the capital.

Yet civilians paid a heavy price. The fighting raged across town, with constant shelling and machine gun fire. With the balance of control shifting, residents mostly hid in basements or cellars with little clear sense of what was actually going on.

Few ventured out in those first days. One who did was the mayor, Yuri Prylypko, who went to provide food and medicines to those in need. He and two colleagues were shot, and their bodies lay in the street until his friend, the local priest Pietro Pavlenko, was allowed to retrieve him. As first reported by Catherine Philp of The Times, Pavlenko had to drag the bodies first with a rope to make sure they were not wired with explosives, before taking them away in a wheelbarrow.

A Good Man

Trim and with clean good looks, Vadym Suslov was a property developer and owner. His home still has a feel of solidity and taste; a BBQ in the large backyard, a well-tended garden, billiards in the garage.

Before the war, the 49-year-old strolled down the main street every day to check on his two rental sites nearby. As Mykola Rymarenko, a family friend, recalled, “Vadym was the kind of person who if he started something, would finish it.”

Soon after the fighting began, Vadym, his wife Inga and their daughter Anastasia had moved in with his mother-in-law, Nadiya Kyrychenko, half a mile away. With heavy fighting on the main street, Nadiya’s house was set back, tucked on a side street behind the large municipal building, around the corner from Pavenko’s church.

The main reason, however, was heating – the weather was very cold and the electricity had been cut off at Vadym’s house. So they moved for comfort and safety. It wouldn’t last.

Orphaned at the age of 12 when his single mother died in a car accident, Vadym was close to Nadiya, and her house was modest but in good repair thanks to his handiwork. The family had lived there until Anastasia was eight.

At the end of the short drive is a large shed, with space for Vadym’s tools and an upstairs storage area with large windows providing a view across the back garden and a field stretching to the train track.

They never dared going up those stairs. The house next door was occupied by Russians, eight soldiers and two BMDs – the Russian version of an armoured personnel carrier – parked outside. At one point a shell landed in their back field, leaving a large crater.

During the frequent shelling, they hid in the cellar, a space cheered by the groaning shelves of the family’s gardening efforts: jars of fruit jams, pickles and peppers, with crates of potatoes for planting stacked on one side.

But it was extremely cold and damp, and soon the electricity here went out too, so they resorted to candles and matches.

Vadym, with asthma, could not stand to be cooped up and refused to go to the cellar. Regardless of bombardments, he remained in the house.

The Battle Peaks

By March 3, the battle in Hostomel reached its peak, with shells overhead and the sound of war constant.

At Nadiya’s, the three women were in the cellar when they heard a loud explosion and then a whistling sound, following by an overpowering smell of gas.

Vadym said a shell had struck the gas works just opposite the house. Several houses were clustered together there, next to the municipal centre. Vadym knew where the valve was and said he was going out to shut it off.

It was dangerous, but there was little choice. Any moment there could be a massive explosion, impacting them and half the town. So, for the first time in days, Vadym opened the front gate, hustled the 25 yards to the valve, screwed the handle hard to the left, then raced back.

It was a heroic act, and also exhilarating. For a man who relished responsibility, it must have been a relief – and no small excitement – to do something after these days.

That adrenaline may have clouded his judgement. Shortly afterwards, he received a call from their elderly neighbours. Something was also going on back at their house, possibly a fire.

“Vadym, there is whistling and burning,” they said. It seemed urgent.

Inga begged her husband not to go, but he was determined. And in a fateful decision, he chose a back route along a trail between the rise of the train tracks and the back fences of all the houses. This, he must have thought, would have provided safe cover all the way.

Standing by the door, Inga watched, as he made his way through the small garden and then headed off, at a jog, hands in his sweatshirt pockets, through the long back yard.

He did not get far. Two shots rang out. Vadym stopped, cried out, “I, I… ,” and collapsed.

Terrified and frozen, there was nothing Inga could do. To go after him would only cost her own life.

So she went inside to where Anastasia was brushing her teeth, and told her that her father was dead.

That was only the start of their agony. For four days, Inga wept in anguish, seeing her husband’s corpse in full sight, unable to do anything.

The fighting continued across the town and regular shelling forced them into the cellar. By March 6, Russian control was beginning to be consolidated and there was less shelling. But still the body remained, in full view.

Four days on, Father Pavlenko came to collect Vadym, as he had done with the mayor and as he was doing elsewhere for other families. The body was laid on an outside table on a covered back porch area, and covered with a blanket.

Two days later, Inga, Nadiya and another neighbour dug a temporary grave in the garden and laid him to rest in a simple ceremony presided over by Pavlenko.

Another War Crime

Vadym and his family could not have known this, but their house had been occupied by Russian troops.

Many windows were smashed, and most of the contents of cupboards were strewn on the ground. The kitchen was a mess, and someone had tried to rip out the oven and hob. The large TV was missing and the Lexus parked in the drive had been trashed.

To defend their positions, other soldiers parked armoured BMDs in several driveways and yards up and down the street.

Remarkably, it seems local residents still sometimes came to the house. A friend of Anastasia’s even crept in at one point and took a photograph of the disarray. A jacket visible in that photo was later no longer in the house.

On March 6, the neighbour’s son, Oleksiy Tuzinskyi, 38, in the house to the left, chose to visit. According to his mother, Liudmyla Vaskiv, he aimed to check on the house and the car.

Like Inga, she too begged him not to go. Shortly after, his father, Andriy Vaskiv, 58, went after him. The neighbours said that Oleksiy had been speaking to the Russians in the house, and that they had asked him to ring his father and ask him to also come over.

We cannot know precisely what occurred, but events moved quickly.

Along the short path between the two houses still lies a jumble of electrical and telephone wires, both with black insulation and bare aluminium tension strands.

The son’s hands were bound behind his back by a several metre-long strand of the black wire. The father’s hands were bound by shorter aluminium wire pulled tight.

Two shots rang out. Liudmyla heard them, but she still had hope. After a terrified hour, she went over to the house, and was sent roughly away at the gate. On the drive right in front of the house, she saw two distinct pools of blood.

There was nothing she could do but return home.

Hiding and Escape

Back at Nadiya’s house, the three women could not bear their proximity to Russian troops. They broke openings in the fences dividing the neighbouring properties, and relocated to the house of their friend Mykola, taking them further away from the Russians.

Being a few doors down was hardly a guarantee of safety. One day, a Russian on the street caught him peering out of the upper window of the guest lodge and shot at him. Mykola dropped to the floor immediately and avoided being hit. On two occasions, shells landed dangerously close.

On March 11, Anastasia switched on her mobile phone, happened to catch a signal, and learned of an evacuation convoy heading out the next day. Mykola agreed to drive, taking Nadiya, Inga, Anastasia, and another neighbour.

When they passed the family’s house on Svyato-Pokrovska. Inga convinced Mykola to stop. She wanted to see if she could take her own car.

Inga walked up to the front door, by now torn off its hinges. Anastasia followed but stopped, crouching low by the entrance. Hearing soldiers, Inga turned to leave and saw the dried blood on the drive. But in their rush, they never looked under the fern trees.

As they left to the admonishment of a Russian soldier, they saw he was wearing a pair of Vadym’s shoes.

The Suslovs made it past the Russian lines, ultimately travelling to Germany for several weeks, while Liudmyla, with her daughter and granddaughter, journeyed to Kyiv as part of a second convoy which was attacked but made it through.

Both families have now returned, but their lives are forever up-ended.

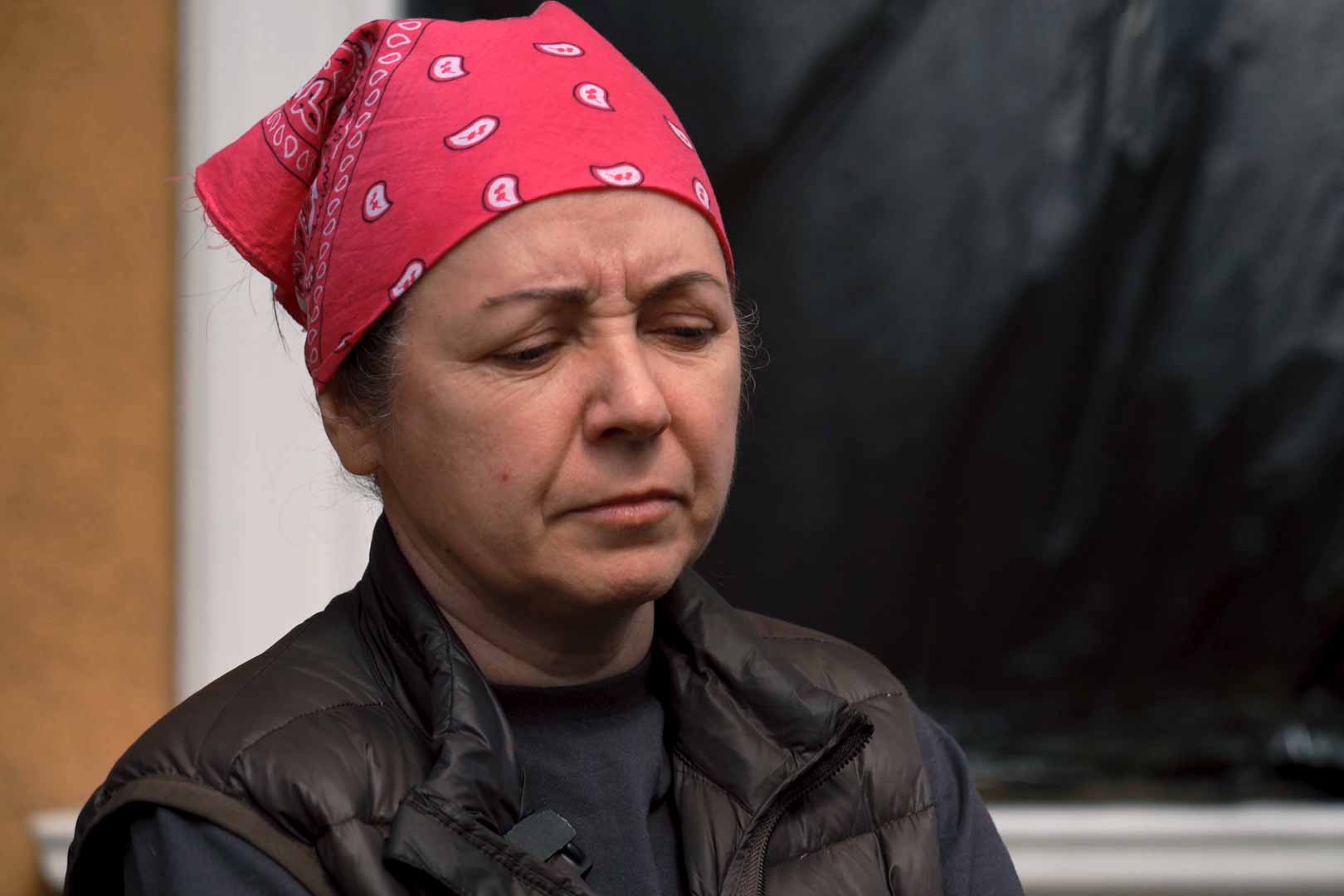

Liudmyla is saddened by the fact that the badly decomposed bodies were cremated and thus she has no grave site.

The morning the Suslovs returned, Vadym was disinterred and given a proper burial at the cemetery, not far from the airport, with Pavlenko presiding. Such rituals provide some relief. But like so many in Ukraine, their homes – and their lives – remain forever stained with tragedy.

Please donate to support the Suslov family appeal or to provide assistance to children who lost one or both parents during the Russian invasion of Ukraine give to Charity Foundation “Children of Heroes”.