Latin America: Journalism Continues to Hold Power to Account

Despite coming under constant attack, independent media are achieving remarkable impact.

When Francisco Rodríguez of Plaza Publica authorised an investigation into the Guatemalan public electricity institute (INDE) published in December last year, he could not have foreseen the effect it would have.

The IWPR-supported report demonstrated that INDE head Melvin Quijivix had abused his position to obtain contracts for his private companies; within a month, the Guatemalan government had fired him.

Remarkably, the President of Guatemala, Bernardo Arévalo and his office specifically thanked Plaza Publica and the independent press for their role in uncovering the abuse.

“Countries with the highest levels of corruption overlap with those with the lowest levels of press freedom.”

“We would also like to recognise the work of the independent press that, through investigations published in media such as Plaza Publica, we were able to discover how this person abused his position in the institution to benefit his personal interests,” the president’s office said in its formal announcement.

An extraordinary result, given the dire risks to their lives and wellbeing that journalists face in countries like Guatemala.

Indeed, Guatemala itself last year saw the jailing of one of its most prestigious investigative journalists José Rubén Zamora on politically motivated charges, leading to the closure of one of the country’s most important watchdog newspapers El Periódico. Rodriguez and his team started conducting their investigation in that context.

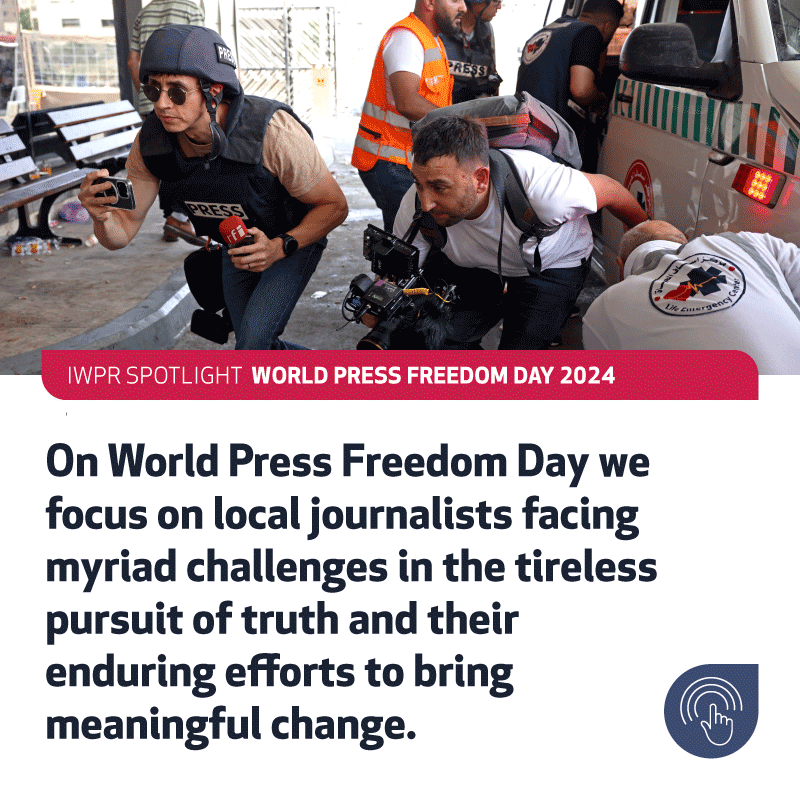

On World Press Freedom Day it is worth remembering the vital role that the media continue to play as watchdogs over corrupted politicians and business interests across the globe, despite tremendous risks.

Looking at indexes collected by international organisations like Transparency International and Reporters without Borders, it comes as no surprise that the countries with the highest levels of corruption overlap with those with the lowest levels of press freedom.

Investigative journalism is most important in the places where it is most dangerous.

And while censorship, continued attacks and a worsening environment for democracy and media in the region mean that it is harder than ever for a report to lead to real life change, IWPR’s recent experience demonstrates that it is not impossible.

“The media plays a vital role as watchdogs over corrupt politicians and business interests, despite tremendous risks.”

Last year, an article by Bolivian journalists Sabrina Lanza and Leny Chuquimia showed how the landlocked country provides its flag to ships with defects and a history of drug trafficking and spurred a member of Congress to contact the families of the crew of a missing ship to help them access legal action. The whereabouts of this ship and its ten crew members have been unknown since 2021.

In September 2023, Focos (El Salvador) published a story showing how President Nayib Bukele’s government was doling out public work contracts to companies with no experience that belonged to allies and officials of his political party. The story highlighted a conflict of interest in a contract given to a company by the Municipal Works Directorate (DOM) and within days, after the article went viral, the director of the institution resigned.

In Mexico, the Chiapas state prosecutor's office began to put together two-day workshops for public prosecutors to train them on how to handle claims about missing people after journalists from Chiapas produced a series about “Ignored disappearances” that showed how the authorities hinder families of missing indigenous people from reporting their cases.

Another article published in Mexico also showed how investigations into disinformation can help clear up the information space during critical elections. In Mexico State’s 2023 elections, Revista Espejo showed how at least seven web pages linked to a marketing agency contracted by the PRI political party for over 75,000 US dollars used disinformation to discredit the Morena Party candidate. After the publication, the CEO of the marketing agency closed his personal social media accounts, and the exposed public Facebook pages and websites, some posing as genuine media, were also deleted.

IWPR sees its role in the world, and in Latin America in particular, to provide the necessary training, contacts, and resources journalists need to overcome multiple challenges to be able to deliver their essential work holding those in power accountable.

And while it is impressive that these and other investigations have led to resignations of corrupt public servants and further proceedings, IWPR has supported hundreds more excellent reports – including several that have received prestigious journalism awards - that were simply ignored by the authorities. In despotic regimes where lawmakers and judges are often controlled and corrupted by both government and private interests, and those in power control the information space, it can be easy for those who abuse their positions to avoid any kind of immediate consequences.

That does not preclude the need for citizens and the international community to be made aware of the shady dealings of politicians and business. And indeed, when crimes and human rights violations are properly recorded using rigorous journalistic standards, they have been used to hold the villains accountable, either through courts, ballot boxes or public protests, even after many years have passed.

These are some of the reasons why it is vital to continue to support the independent press, and even more so in the places where they are most attacked and beleaguered.

On World Press Freedom Day, we express our awe and admiration for our colleagues who in so many contexts have become the last line of defence for free expression, access to information and accountability for leadership.

Dhaniella Falk is IWPR's Latin America & the Caribbean Programme Director.