Orikhiv: City on the Verge

The few residents who remain in the shattered town await the next offensive, from whichever direction it comes.

Orikhiv: City on the Verge

The few residents who remain in the shattered town await the next offensive, from whichever direction it comes.

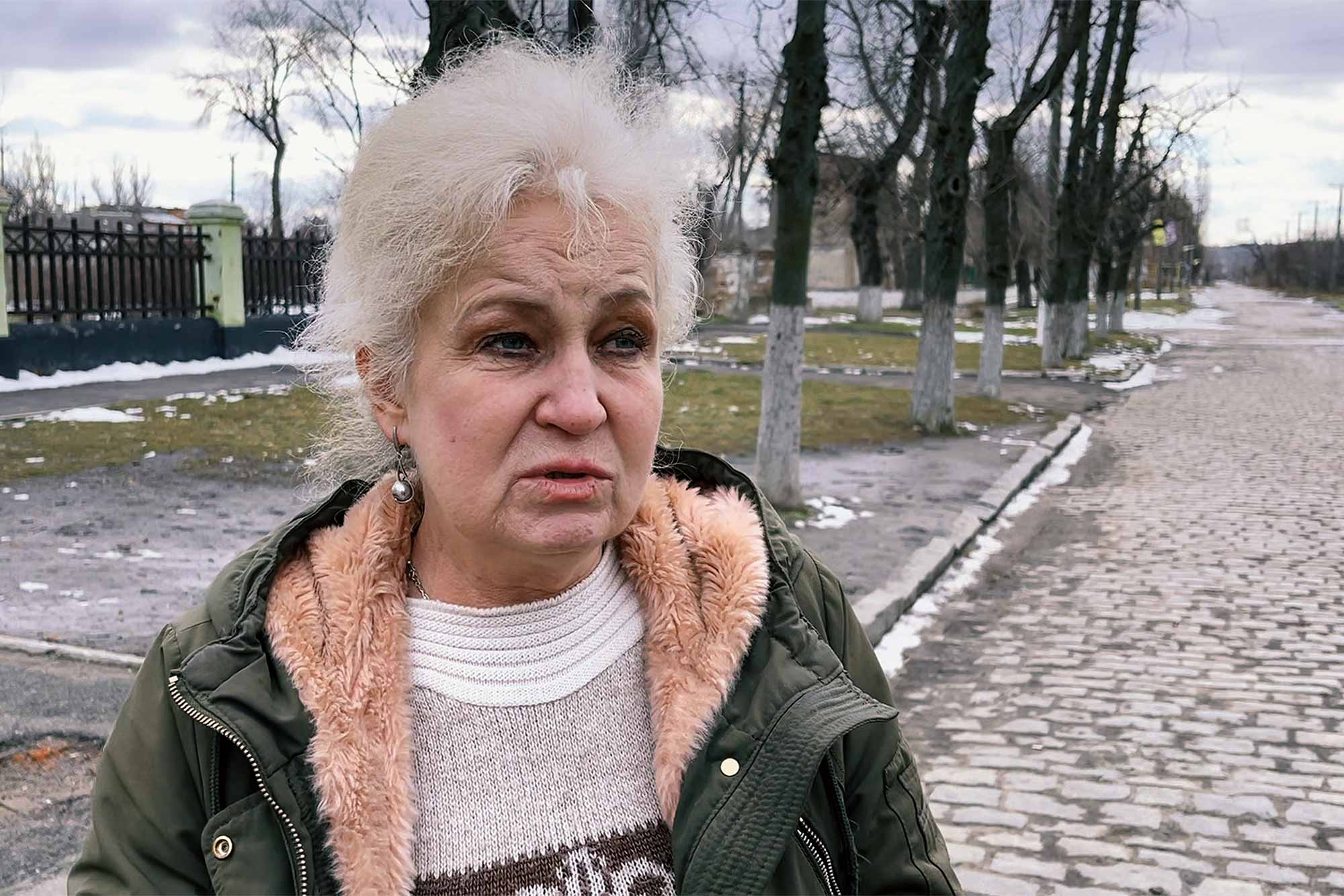

“You got lucky here, we are not being fired on today,” said Lyubov Yarova, 59, a council member coordinating humanitarian support in Orikhiv. “But this silence is scaring us, because silence means they are going to try to advance again.”

Such are the desperate calculations in this shattered frontline town, 65 kilometres southeast of Zaporizhzhia. Russian forces are just a few kilometres away, and the town is almost totally abandoned.

Yet a reduction in the near-constant sound of bombardment – which has damaged or destroyed every building in sight – nevertheless signals to Yarova that even worse may be in store.

Yarova was speaking outside the heavily damaged town hall. Only the basement is now usable, pressed into service an aid distribution hub and a so-called invincibility point where the few remaining residents can access the internet and warm themselves.

While generators hum loudly, a truck is preparing to make the rounds to supply fresh water to the scattered households. The sound of rocket fire on the town’s outskirts is ever-present.

“During last month, the Russians were advancing on our city from a few directions. So we couldn't even come out from our basements. We hid there so not as to be shot and killed,” she said. “My personal feeling is that they’re preparing to advance again.”

With Russia concentrating forces in Bakhmut and other points in the Donbas, such moves could be feints to keep Ukraine forces alert. But they could equally be indications of early battles in the well-trailed new offensive.

Whatever the timeframe, the few remaining residents of Orikhiv and its surrounding villages – no more than 2,000 now, from a pre-invasion population of 20,000 – are sure they will see more war, and probably soon.

In a triangle connecting the industrial city of Zaporizhzhia, Russian-held Melitopol and the devastated seaside steelworks town of Mariupol, Orikhiv is right in the middle at an intersection of several key roads.

If Russia aims to open a new front, this could be a target. Equally, if Ukraine aims to split the Russian territory, the most obvious route runs through Orikhiv to the Azov coast. Any location with a concentration of Ukraine troops will attract fire.

There would seem to be little of value otherwise to fight for in this town, so thoroughly has it already been ravaged.

The roof and upper floor of the pink town hall are smashed. Nearby, a grad missile shell remains cratered into a tree.

Across the street is a sprawling building, its white entrance emblazoned with commemoration of its service as the town’s first girls’ school

Over recent months it was used as a distribution centre for humanitarian aid. Now it is bombed out, the interiors all burned, windows all boarded.

The devastation stretches in every direction. Neighbourhood after neighbourhood, hardly a single structure is untouched – roofs collapsed, walls blasted, shrapnel marks omnipresent.

The town is so underpopulated that it is hard to find residents along the deserted streets. A drive around the Cheremushky neighbourhood at one end of town, previously home to several thousand people, reveals every house destroyed, every lane abandoned. Only cats and dogs roam.

In a small field behind some houses, a sole Ukraine army tank is stationed, and nearby, in the shadow of a row of heavily damaged residential blocks, two Ukrainian solders – one in a helmet, the other with long hair swept back in green bandana – walk by on sentry duty, eyeing visitors warily.

Oleksandr Piliay, 48, lives in one of the blocks and helps distribute humanitarian aid.

“The heaviest days were in the middle of January. There were hundreds of rocket launches a day,” he said. “It was very scary then. They were trying to capture the city. We could hear machine gun fire and fighting.

“Thanks to the fact that people left town, there are not so many casualties,” he continued, pointing to one building with 150 flats, where he says only one person now lives. There are no more than 30 in total over the network of blocks.

A route back to the centre via an underpass offers a shortcut, but the bridge pier is marked with the word Mines, with a skull drawing.

Just past a checkpoint, a woman is collecting walnuts.

“The bombing was so intense…” said Iryna, 62, becoming tearful. “People say to me why don’t you leave? But this is my home, I was born here. We love our city and will not abandon it. We are not afraid of those who shoot, we are only afraid of the weapons they use.”

She praises the workers in the city who provide aid and water and do their best to keep the lights on, noting that two young electricians were killed. “They were not afraid,” she says.

A few streets down, a man surrounded by several dogs seems happy to be out of his house.

“In the beginning, it was scary and we were hiding in our basement,” said Oleksandr Lanchyk, 58. “Right now no one does that, because you can’t save yourself if a rocket is launched at your house.”

Of 100 people in his immediate area, he says that only ten are left.

Lanchyk’s roof was hit by a shell in October, setting the house on fire. He and his son were able to extinguish the flames, only for the house to be struck again some time later. Two neighbours were killed by a direct hit.

At the town hall, council member Yarova explains that Orihkiv starting taking shelling early in the war, and the majority of the population left in the spring.

The remaining residents are either elderly, caring for large numbers of cats and dogs, volunteers, rescue workers and those like herself and a handful of others with the city providing aid and support to keep the town functioning. A small police force is also in place.

The town has adequate humanitarian aid, she says, but most of the city is without electricity, which also means no running water – hence the deliveries, which that day supplied 100 households. There is also a shortage of lanterns, generators and medicines. There is no medical facility, and soldiers are asked to take people needing urgent care to a neighbouring town or to Zaporizhzhia.

“In peacetime, I am the director of a children’s art centre,” Yarova says. “I have tears in my eyes when I think back to how we lived and worked, how much joy I had working with children. There are up to 30 children in the city now, and we are still taking care of them.”

“I never get used to that,” she continued, as another explosion echoes. “And it's painful to look at the town and the state it’s in. That is why I stayed here, to meet victory in my city and to rebuild the city after we have won.”

Translation and additional reporting by Mykhaylo Shtekel and Anastasia Kucher.