Looking for Mikelson: Apartheid in the Caribbean

Uncovering systematic human rights abuses against Haitians.

Part I: The Man on the Roof and the Underground Railway

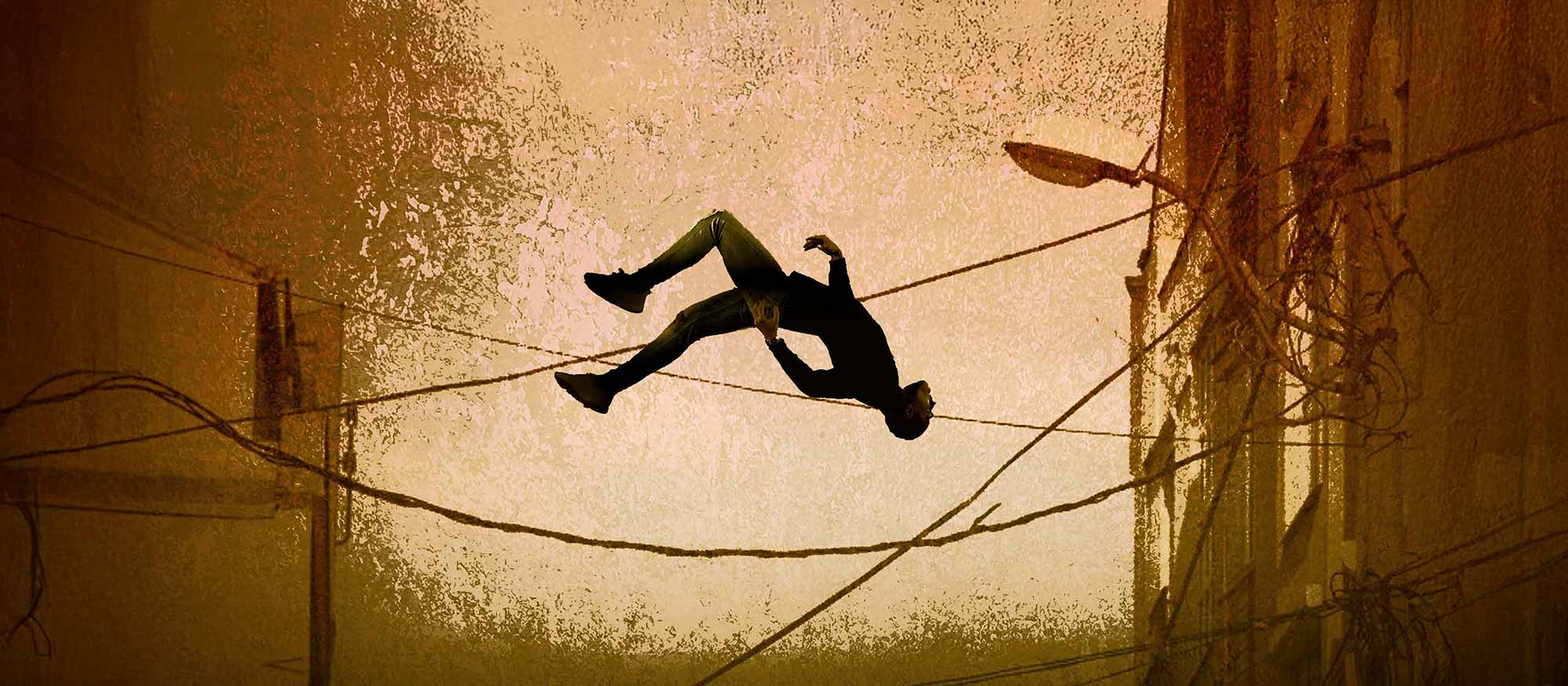

In the video, a policeman chases two black men fleeing across a red roof. He wants to corner them, but one of them outruns him with a feint and runs away. The other, a thin figure wearing a reflective vest like those worn by construction workers, is trapped. The officer catches him and grabs him by his clothes. The man tries to break free, but the policeman drags him to the edge of the roof.

And throws him off.

"Baba, Baba (My God, my God), they killed him!" exclaims the woman recording the video on her mobile phone in Creole, the Haitian language. The man in the reflective vest disappears from view. The woman is left sobbing.

I received the video on the afternoon of October 4, two days before landing in Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. The source who sent it to me knows nothing about the three protagonists, nor about the woman who is wailing. Nor does he know where it was filmed. The low, tin-roofed houses resemble those in any of the neighbourhoods where, according to human rights NGOs, the Dominican authorities detain hundreds of young people, children and women - with and without their babies - locking them in rolling cages before deporting them to Haiti.

What my contact is convinced of is that the scene took place between the last days of September and the first days of October 2024. The government of Luis Abinader has promised to remove 10,000 Haitians from the country each week, and the migration police, the national police, the armed forces and part of the Dominican population, some of whom are arming themselves, are working together to fulfil that promise and "defend" themselves against what the official narrative has called an "invasion." During the month I will be reporting, the government will deport nearly 28,000 Haitians. My contact also believes that the man in the vest is dead. That would be normal after a fall like that.

For me, this video represents the essence of this violent logic that seems to have possessed the Dominican Republic against its neighbours: two black men fleeing across a rooftop, a uniformed man chasing them, a man thrown like a bag of rubbish, a woman crying.

Similar videos showing police brutality against black people sparked outrage and collective mobilisation in countries such as the US. The Black Lives Matter movement, which led to the largest civil protests in the US in 60 years, was born after a video showed police killing George Floyd while he cried out, "I can't breathe."

The largest civil unrest in California in the 20th century erupted after a mostly white jury acquitted white police officers for the beating of African American Rodney King in Los Angeles, even though they were immortalised in a video recorded by a neighbour shouting things similar to what I hear in the video I now have in my possession.

That is why, upon arriving in Santo Domingo, I am accompanied by what will become an obsession: to find the man in the video, or his grave, or someone who misses him; to be able to answer what forces are at work that prevent trials, investigations, protests and fire.

A police officer throws a man off a roof somewhere in the Dominican Republic amid the government's policy of mass deportations of Haitians.

***

I have an appointment at MOSCTHA, an NGO supporting the Haitian population, but when I arrive at the premises, a group of ultra-nationalists in dark clothes calling themselves Código Patria have blocked the entrance. They are not allowing anyone to enter or leave. There are about 50 people with Dominican Republic flags and portraits of Juan Pablo Duarte, the hero who led the war of independence from Haiti in 1844. They have placed a loudspeaker in front of the entrance to the institution and are shouting anti-Haitian slogans.

"We don't want Haitians here, send them back to Haiti!"

The institution functions as a clinic for Haitian migrants with and without papers. It has a radio booth where it broadcasts in Creole to the country’s Haitian community, and a special programme to care for people with HIV.

"If they don't leave, we'll get them out. The Dominican Republic is for Dominicans!" shouts Wendy Santiago, the founding leader of Código Patria.

After about two hours, the slogans and insults stop, they put away their loudspeakers and flags and leave. The clinic reopens and the patients reappear, as if they had been hiding nearby.

In front of the clinic, I am greeted by Joseph Cherubin, the director of the institution. I am here because he is going to give me access to a network of Haitian leaders in the Dominican Republic. These are union representatives, evangelical pastors, and Ungans, Mambos, and Bokos, as the priests and priestesses of the Voodoo religion are known, who have established a rudimentary and quasi-clandestine system of support for the migrant community.

It is this network that organises collections to cover the medical expenses of sick or injured Haitians, provides shelter and protection when immigration raids intensify, and documents the constant harassment by the authorities and ultra-nationalist groups. It is this network, with few resources and limited international connections, that stands between many Haitian migrants and death or other horrors.

Networks of this kind have accompanied the African American community almost since the time of the great kidnappings in Africa and the years of colonialism and slavery. In the 19th century, Harriet Tubman, a black woman enslaved in the southern US, led an underground network that fought for the abolition of slavery and supported the escape of slaves from the South to the abolitionist states of the North. This network was known as the "Underground Railroad," and it is estimated that at least 100,000 slaves used it to gain their freedom.

In 2017, writer Colson Whitehead won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Underground Railroad, based on this historical episode, and in 2023, director Barry Jenkins adapted it into a series for HBO.

In the Dominican Republic, a similar railway, created by black men and women, operates today. Like its predecessor, it must operate in the shadows if it is to survive. Unlike its predecessor, however, it does not seek to free people from slavery and give them their freedom, but rather to ensure that people are treated as humans and remain where they are.

Cherubin takes me to his office and explains that there are raids to hunt down Haitians in the mornings and afternoons. He tells me that the police seem to have daily quotas and that if they don't meet them, they go into the neighbourhoods at night to kidnap people. He takes out his phone and opens folders containing videos and photographs sent to him over the last month by Haitian leaders across the country. The file seems endless. It's like a huge menu of horrors.

He shows me dozens of videos of black people running from their uniformed pursuers, often black themselves. In one, a woman is screaming that her newborn baby will starve to death if she does not return, while they insult her and drag her towards one of the cage trucks that the government has set aside for deportation. Another woman presses her baby against the bars of one of the trucks so that it does not fall onto the street while the truck is moving. Then there is a video showing three uniformed men beating a black man on the head with a club.

"Stand up, you fucking Haitian devil!" they shout as the man convulses on the ground, bleeding.

He shows me videos that have been recorded by people detained and in the custody of the Dominican government: Haitians fainting, crammed like cattle into large unventilated warehouses; people shouting in Creole that they have not been able to speak to their families or have access to lawyers for eight days; people defecating in bags inside rolling cages after 12 hours of confinement under the sun.

Many of these Haitians are in a huge detention centre located in the town of Haina, the same place that for decades served as a destination for Dominican holidaymakers and which, although it sounds like a bad joke, still retains its old name: Haina Holiday Resort.

Among these videos, I cannot find the one of the man who was thrown off a roof by the police. I tell Cherubin I want to find him. He tells me that the network will get to work and that he will find him for me. Him or his grave.

The Haitian "underground railway" assigns Moisés, a man in his forties, as my guide. He is bald, solidly built and has a perfect smile. He is an old Caribbean fox who knows how to move around the Haitian neighbourhoods in the midst of a police hunt.

Two days after my visit to the NGO, Moses calls me on the phone, "He's alive."

***

The woman in charge of the door at the trauma hospital in Santo Domingo lets only me in. She shoos Moisés away, like a child, or rather like a fly. On the third floor, in room 204, on a stretcher, bandaged from the waist up and a pale, pale grey, is Keken, a 22-year-old Haitian. His brother is with him, but neither of them speaks Spanish. They have to resort to sign language to tell me their story. They call one of the leaders, an evangelical pastor, and he translates for me over the phone.

On the morning of October 1, 2024, Keken was on his way to work at a cement block factory when the police chased him amidst one of the new immigration raids. He climbed to the third floor, but the police ran after him and cornered him. Keken fell to the ground and was left unconscious with a broken hip and several broken ribs, as well as numerous fractures and bruises. The police left him bleeding in the dust on the street.

The Haitian underground railway has been taking care of him since then and they have managed to get him a place in the hospital. But in order to operate on him, they are asking for several bags of blood and medication worth about 300 US dollars, which the network has not yet been able to obtain.

A group of doctors enters the room, where other badly injured men are also lying, and ask Keken questions, but he only raises his eyes to his brother, who in turn glances at me.

I tell the doctor that I am a journalist and that I am writing about this case and others.

"We treat all kinds of people here, it doesn't matter if they are Haitian. We have to treat them the same," he says automatically.

I explain that they don't speak Spanish but that they can use the same pastor as an interpreter. He refuses. I ask him how they communicate with Haitians who don't speak any Spanish.

"We have a colleague who speaks Creole, but there are no interpreters here. Sometimes they understand something or there is someone here who can translate," he tells me.

If there is no one, as in Keken's case, then nothing is done, and they turn around and leave without informing the patient about their condition. I ask him if there are many foreigners in similar conditions.

"Yes, there are several Chinese, but they are more responsible than the Haitians," he tells me and continues on his way.

Keken arrived in the Dominican Republic just a year ago. He was born near Cap-Haïtien and came here looking for work and fleeing the violent chaos of gangs and famine. It is not certain that he will ever walk again. If he does, it will certainly not be as he did before.

Keken is not the man on the roof I am looking for; it is another man on another roof.

***

"We'll keep looking," Moisés promised me the day we visited Keken in the hospital. I've been in Santo Domingo for a week when he calls me again.

"A leader has found him in Villa Mela," he tells me, referring to a neighbourhood with a large concentration of Haitians. He tells me that the network has spread the word that there is a journalist writing about cases of abuse against Haitians and dozens of leaders, pastors, Bokos, and activists from all over the country are writing, sending videos, photos and statements. A Haitian evangelical pastor has written to the underground railway and says he knows where to find the man on the roof. He says that it seems to have happened on the territory of a leader named Vania.

We travel together with this pastor, whose name and details it would be prudent not to reveal, to a densely populated neighbourhood an hour away from Santo Domingo.

Vania welcomes me into her office. She is a plump woman with hair down to her chin. She has a kind face and a contagious smile. Like Cherubin, she runs an NGO supporting the Haitian migrant community. Hers is called the Socio-Cultural Movement for Community Development. She tells me about the crisis in her sector, about thousands of displaced Haitians, about children who are left alone when their mothers are taken away. Like Cherubín, she has her own archive of terrifying videos.

The few NGOs defending Haitians in the Dominican Republic receive dozens of videos from across the country showing human rights violations suffered by this community.

Vania says that the offensive against the Haitian community is getting worse over time, that it seems to be cyclical. History seems to prove her right.

In the 1930s, dictator Leónidas Trujillo banned many expressions of Haitian culture in the country and organised one of the most brutal massacres in Latin America in 1937, with the murder of between 5,000 and 15,000 Haitians in the border region of Dajabón. The tyrant was assassinated in 1971, but he left behind the seeds of ethnocide that are blossoming once again.

In 2013, a constitutional reform stipulated that all children and descendants of "illegal" Haitians, despite being born in the Dominican Republic and having birth certificates and identity cards, automatically cease to be Dominican, with the loss of rights that this entails.

According to Haitian organisations—the lack of official statistics does not allow for a more precise figure—between 500,000 and more than one million Haitians currently live in a country with a population of just over 11 million.

More than 200,000 people are condemned to statelessness; they are not Dominican, but they are not Haitian either, since they were not born there. They are condemned to float in the uncertainty of being illegal wherever they are.

The Community of Organised Haitians, a group of pro-migrant institutions, has documented hundreds of cases in 2024 of children, pregnant and breastfeeding women caged in appalling conditions and deported, and people imprisoned in rolling cages without the minimum conditions required by international treaties. Over the past five years, this group of NGOs has sent an annual report documenting these abuses to the Attorney General's Office, without any investigation being launched.

Hate speech has also taken root in society. Dozens of anti-Haitian groups threaten, kidnap and attack Haitian leaders and organisations with total impunity.

These are not isolated cases. These are not rogue police officers. These are not groups of lunatics who hate their neighbours. Since 2021, when the Haitian exodus began to increase as their country collapsed, the Dominican Republic has deported 400,000 Haitians, according to the International Organisation for Migration. What is happening on this Caribbean island is a system of racial segregation. It is apartheid.

Vania shows me one of the most effective measures for protecting migrants. It is a video that her network has produced for the Haitian community. In it, a young woman explains what they should do if they are pursued by the police. She tells them to stay calm, try not to walk alone, teaches them a few words in Spanish and emphasises that they must not fight or run.

When I ask her about the boy on the roof, Vania says he is barely alive in one of the neighbourhoods of Villa Mela.

***

The following afternoon, Moisés guides me to Villa Mela. Haitian workers are leaving the construction sites and filling the slums. A police patrol has been following us since we arrived in the area.

"Stay calm, they won't do anything to a journalist. They want to take our money, but they won't do anything," Moisés tells me in broken Spanish and with a disturbing calm.

Before we reach the entrance to the neighbourhood, the patrol car cuts us off. Two uniformed men surround the car like cowboys, their hands on their guns.

A policeman who identifies himself as Officer Reyes takes my papers and writes down my details in a notebook. He doesn't even ask for the vehicle documents.

"Haitian, do you have your papers, are you in order?" the policeman snaps at Moisés, who hands them over silently, without taking his defiant gaze off the officer.

They rummage through my things and destroy a box of granola bars that I had kept in the back seat of my truck in an attempt to be healthier. They ask us where we are going. I don't answer. They leave, but follow us for several blocks until we make a few turns and head into the hills.

We climb up into the neighbourhood along muddy streets, dodging the huge puddles left behind by last night's rain. Most of the houses are small, with tin roofs and small wooden cubes resembling barracks.

After a long drive, we arrive at a small house. Inside, face down on a small wooden cot, is Daniel, moaning in pain. His sound is a soft, long groan, like someone who has been hit in the stomach. Talking hurts; moaning seems to hurt him too. He has about six bullet holes in his lower left back.

Daniel was shot in the back by a police officer during a deportation operation.

A few days ago, two police officers tried to arrest him while he was on his way to work at a construction site. Daniel did not stop and tried to escape. Then one of the officers shot him in the back. The shot was fired at close range, and the pellets from the shotgun had not yet expanded much, only a few centimetres. The shots didn't go through Daniel. They knocked him down.

According to his family, the police forced him to walk on his knees for a while and tried to take him away. But when they saw that he was bleeding heavily and that the neighbourhood was starting to get rowdy and groups of young men were gathering on the corners in outrage, they left him lying in the dust.

Before I leave, Moisés tells me that he will take my car. He insists that the police officers who stopped us are the same ones who shot Daniel and believes that they could arrest us or screw us over in some way. The vast Haitian railway network needs to get these stories out of the neighbourhood and they don't want to risk my photos, recordings and videos ending up in the hands of the police. They put me on a motorbike and take me away through other alleys.

***

After my failures, I believe that I will not find that man on the roof or his remains, that this case will be forgotten, that his life, or his death, will only pass into posterity as an anonymous video where an anonymous police officer throws a nameless man who had come from a dying country to work and who that day was wearing a reflective yellow vest and blue trousers into the void. But the underground railway is making itself felt again.

Rony, one of the most active leaders, whose name is of course not Rony, tells me that the leaders have sent him the same video. He tells me that the boy is alive and under the protection of Pastor Wilson, whom he names as if I should know who that man is.

After a dramatic silence, he tells me that he is a Haitian leader operating on the other side of the country, in Punta Cana, the tourist gem of the Dominican Republic. That pastor is being persecuted by the Dominican authorities for his constant denunciations and for keeping an extremely detailed record of the abuses, murders and mistreatment of the Haitian population by the authorities. He has been threatened several times, which has made him wary. It is very difficult to talk to him on the phone. Other Haitian leaders who tell me about him describe him as a tough man who, in addition to being a community leader and pastor, is a private detective. They say he watches his back very closely.

If I want to find the man on the roof, Rony assures me, I will have to go to Punta Cana, 200 kilometres from Santo Domingo, and speak to Pastor Wilson in person.

After walking blindly in search of a ghost, the information that arrives via the underground railway breaks the anonymity of the man on the roof: Mikelson, the man on the roof is called Mikelson.

***

Part II: Police Kill in Punta Cana

The police have killed a Haitian! Run!" says Pastor Wilson on the phone. Twenty minutes later, I'm doing my best to follow him along dark roads deep inside Punta Cana. The pastor is driving a 2005 Nissan Frontier pickup truck, or what's left of it. The car has been fitted with larger tyres on one side, but he still manages to get it up to 120 kilometres per hour. It is nearly midnight on a Thursday and the city is possessed by partying, as it is almost every night.

Near the beach paradises, European and American tourists and the odd wealthy Latin American are celebrating. In the colmados (shops) of the neighbourhoods, Dominicans drink cold beer and listen to loud music. But in the Matamosquitos neighbourhood, in the Fiusa sector, Haitians have become a discontented, angry mob because the police went up the hill and killed people.

We are greeted by a mob of young men who form a human wall at the end of one of the alleys in Matamosquitos, the southernmost and poorest part of the neighbourhood. Pastor Wilson has made caps for himself and his collaborators with gold embroidery that says "Human Rights".

He is 46 years old, a robust man with a loud, serious voice. He was born in the Dominican Republic to Haitian parents who came in the 1950s to work in the sugar cane fields. He owns a small fried chicken business and also works as a private investigator, filing complaints with the prosecutor's office, the police and immigration authorities. Although he holds no official position, Haitians recognise him as a leader.

I'm the only one here who isn't black, and the Haitians get aggressive when they see me get out of the car. They think I'm Dominican. But the pastor speaks to them loudly, in a mixture of Creole and Spanish.

"International journalist, he's the international journalist, calm down, calm down," he tells them, almost scolding them. I stick close to him, as close as I can, and we move forward.

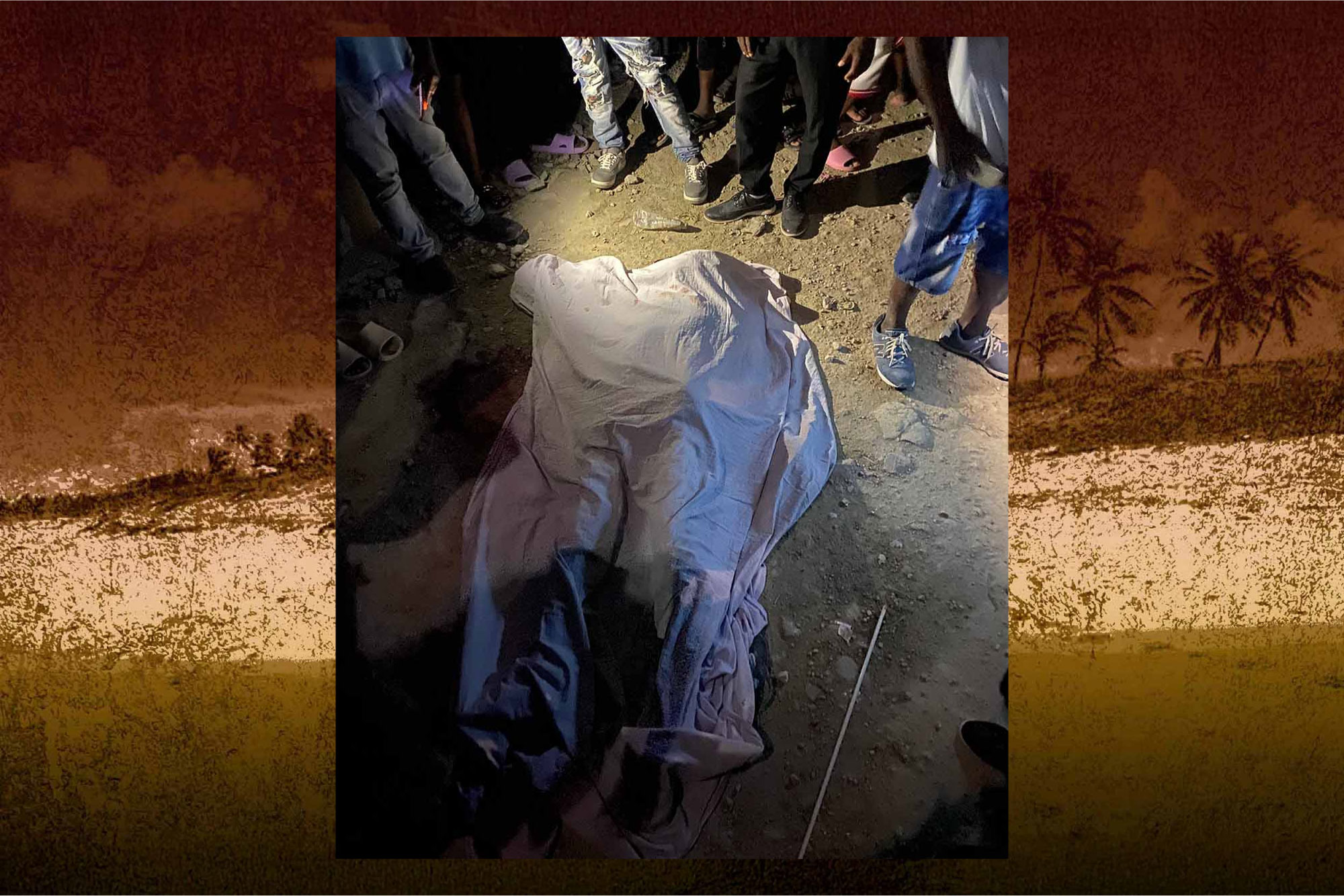

A human tunnel opens up until we are in front of Gems Joacin. He was killed by Dominican police officers less than two hours ago. He has at least three bullet wounds in his chest, possibly one in his neck, and his eyes are still open.

"Look, here are the bullet holes, if they shot him from close range," says Fifa, a Haitian community leader, who with her loud voice manages to calm the agitated crowd of young men. Fifa pulls aside the white sheet she has placed over Gems to protect the privacy of his death, and almost puts her finger in the holes to show me that a bullet did indeed pass through there.

The story she recounts is corroborated by at least 150 people who nod their heads and show videos; that the police came to capture Haitians to deport them, that they have done so several times this week, and that this sparked a small riot in which Gems got the worst of it. They explain to me that a few days ago, most of the construction sites in Punta Cana, where most Haitian migrants work, paid their workers. They say that these days, the unwanted police visits are more frequent and more aggressive. They claim that the police demand money in exchange for not taking them away and handing them over to immigration.

At around 11 pm tonight, when they saw the police patrol, most of them ran away, others locked themselves in their tin shacks to wait for darkness and silence to hide them, and others grabbed the weapons that poor people use when they get angry: stones.

Gems did none of these things. When the police killed him, his hands were full. He had just come from buying ten pesos worth of ice, two flavoured juices and three loaves of bread for dinner at the corner shop, about 60 metres from the rented tin shack where he lived alone.

His last purchase was still lying a few centimetres from the pool of blood that had spurted from his mouth, but the bread and juices soon disappeared. It's not just the police who plague the neighbourhood, but also poverty and hunger.

Fifa and the others still refer to Gems by his name; he is still him, not that. Fifa, Pastor Wilson, the other four leaders who accompany him, and the mass of people from the neighbourhood believe that the police will come to take the body away. They say it's normal, that it's happened before. Pastor Wilson, who sped up his beat-up car in the hope of finding Gems alive, is now focused on saving his remains and, with them, he says, his identity.

"We're not going to let them throw him on the pavement like he's rubbish," he tells me, his face angry, his expression warrior-like. That sea of young men insists that the police want the body, they tell me in the best Spanish they can muster, that they are going up for Gems. They still call him by his name. A group picks up stones and shovels and prepares. They are going to defend Gems. They are determined to not let him be turned into a thing.

Fifa's megaphone voice manages to control this tide of angry testosterone. She sounds like a mother scolding her children. In this part of the country, where construction is the main occupation of the Haitian community, there are many more men than women, most of them young. They obey this surrogate mother, but young blood mixed with death and indignation creates storms that do not easily subside.

A group starts kicking a tin door and there is an outbreak of chaotic violence. They don't know who to hit, so they hit each other. But Fifa, with her deep voice like old iron, once again manages to calm the sea. Between her and Pastor Wilson, they do an exercise as if from primary school.

"If the police come, the forensic team, we'll stay calm, right?" And the crowd responds with a "Yeah" that conveys more violence than peace.

A small, old pickup truck appears in the alleyways. It is driven by two young, muscular Haitians.

"We've come to pick up a body. The police sent us," they say.

Then it starts, a strange sound, like a lion just before it roars. It comes from the chest, just above the stomach of those large Haitian men. The two men freeze. Fifa and Pastor Wilson tell them to leave, to leave quickly, before the sound turns into something else and there are two more bodies in the neighbourhood. The young men leave in their pickup truck, but the whole neighbourhood has now had their fear confirmed: the police want the body.

The pastor makes non-stop calls and in less than an hour a small minivan with a funeral home logo arrives. Two men roughly load Gems, who is already stiffening.

The pastor's beat-up pickup truck and my rental car escort Gems' body at full speed through dirt roads and puddles with a haste that has nothing to do with the solemnity of death.

As we leave the neighbourhood, we are stopped by a police roadblock. There are two patrol cars with at least seven officers. The community leader travelling with me as my co-pilot puts his hands to his head.

"It's an ambush, they want the body," he says. They ask us all to get out of the vehicles. They pull Pastor Wilson out of his car and rudely tell me to get out too.

They look at me with fear; they weren't expecting outsiders here. I try a bluff that could easily backfire.

say as loudly as I can, "Good evening, I am a member of the international press. Who is in charge of this operation? I need them here right now."

The young policeman in front of me stammers, telling me that he is not the boss, that the boss is not there, that I should go to the station. He says something to the others and they get into the patrol car. They see the body, take photos of it, but don't dare to take it away in front of my camera, which I have already turned on. So they order the driver of the mini-van to follow them to the station.

The pastor won; it will be more difficult for them to get rid of the body now. It's already been recorded and you already know his name. Everything indicates that thanks to the work of Haitian leaders, Gems Joacin, the construction worker who left somewhere in Artibonit, Haiti, around 2004, when he was very young, looking for a better life, will continue to be himself and not “that”.

***

In the last three years alone, Punta Cana, the territory where Pastor Wilson is resisting the authorities, has welcomed approximately nine million tourists. This place has brought the concept of a tropical paradise to life and is by far the most luxurious spot in the Greater Antilles. Originally known as Drunkard's Beach or Fisherman's Beach, it was founded in the late 1960s by a group of American businessmen who saw the overwhelming potential of this piece of Eden. Since then, more than 70 luxury mega-resorts with golf courses and private beaches have been built, along with hundreds of smaller hotels. In total, there are 44,000 rooms available to accommodate holidaymakers.

Dominican magnate Oscar de La Renta was enchanted by the crystal-clear waters and decided to build a private mansion and hotel here, the Tortuga Bay, which is considered the most luxurious place on the entire island of Hispaniola.

The romantic Spanish singer Julio Iglesias did the same, building a mansion facing one of the white sand coves with turquoise water. Punta Cana attracts celebrities like honey attracts ants. Shakira, Marc Anthony, Rihanna, Jennifer Lopez, Justin Bieber and a string of big businessmen from all over the world have passed through here.

But this paradise is not just for celebrities and millionaires. Thousands of Americans and Europeans arrive on cruise ships every day, and the nightclubs and bars make every day and every moment feel like Saturday night.

All this rapid growth, all this construction, needs to be turned into columns, roofs and beams, and these things don't build themselves; money does not yet have that power over the elements. More than 111,000 Haitians have arrived or been brought here by large construction companies to turn these ideas of grandeur into something tangible, according to estimates by local researchers.

Tourists also need people to welcome beachgoers and offer them clean towels when they come out of the sea or the pool, someone to tidy their rooms and serve their lobsters. The large tourism industry employs at least 54,000 Haitians, according to a study by the Institute of Migration of the Republic.

The same people who are being persecuted by Abinader's policies are essential to several economic sectors in the country. That is why merchants in various markets have protested against the large deportations, saying they are selling less than half of their products due to the absence of Haitian buyers.

Complaints are also coming from the agricultural sector, especially banana and sugar cane growers. Even the Minister of Housing, Carlos Bonilla, has acknowledged that the deportations are seriously affecting the construction sector. Everyone's complaints revolve around the same thing: the deportations are causing a shortage of workers, which is depressing production and domestic consumption.

The issue of human rights is not taking a back seat, nor is it being relegated to second or third place. It is not even on the table.

One day in October, in the late afternoon, as the sun seems to blush over a blue sea, an American couple gets married on the beach. The staff at their hotel have set up an altar and tables for the perfect photos. The man, an African American man almost two metres tall, puts the ring on his wife's finger just as the afternoon paints its last scene. Further on, a group of models are photographed as they pose proudly, impossibly, with the expression of divas on their faces.

A group of French families float in the calm waters of the Caribbean. Behind them, on the sand, watching over the beachgoers' belongings, arranging sun loungers, handing out towels and serving wedding champagne, are the Haitians, always Haitians, always behind, always living in the hills, like Matamosquito, where they can build their shacks on dirt floors and tin roofs. A few hours after this wedding, the police will kill Gems Joacin.

***

Pastor Wilson had briefly confirmed that Mikelson was alive, under his protection, and he would guide me to him. But before that could happen, he called for another reason.

"You have to come, I have a terrible case here. I'm at the hospital with a boy who... you better come, I'll show you."

At the Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia General Hospital, at the end of a corridor, separated from the other patients, Wikey, the skinned man, was moaning.

Visitors are not allowed in the area where Wikey was, but Pastor Wilson smuggled me in like contraband with the complicity of a Haitian security guard, who winked at him when he saw him accompanied by a white man. Wikey is a thin young man with short dreadlocks. He had a lost look in his eyes and responded to my greeting very slowly, very softly, as if we were in a dream.

Life seemed to have already left his body. He spoke as if from the bottom of a well. Almost half of his body was skinned, without the skin and flesh that usually surrounds the bones. From his right knee down, he was blackened, as if scorched.

"He was run over by a jeep, it seems on purpose, in the early morning, and dragged along the street for a whole kilometre. He came loose on a curve because the man never stopped," Pastor Wilson explained to me. He told me that the boy's neighbours had taken him to the municipal hospital in Verón, Punta Cana, some time between between October 1 and 3, but that he had been sent home.

Wikey had languished for 17 days in his house with a dirt floor and everything else made of tin, plastic and wood. Those were the very days when police immigration raids were at their peak and his neighbours fled the village. He was left alone with a little rice and water, trying not to make any noise and with the door locked, hoping not to be discovered by immigration, the police or the army.

He had spent just over two weeks like this, with his body infected, hungry and dying, until Pastor Wilson found him, moved him into his pickup truck and called his contacts to get him admitted to this other hospital.

At the hospital, Pastor Wilson took it upon himself to tell anyone he came across that he was accompanying "a man from the international press". A nurse arrived with a stretcher and took Wikey away for X-rays. Then they moved him to a larger room where, it seemed, he would finally be seen by a doctor.

Three young women were chatting casually in the room about a piece of furniture that one of them was going to put in her house. The women did not hide their horror when they saw the skinned man. The doctor approached to examine him and ask him questions, which Pastor Wilson hastily translated. When they explained that he had been infected for 17 days, she reacted with great annoyance.

"Seventeen days you've been like this? Young man, looking at the state you're in, and you've only just come to the hospital. My God..."

Pastor Wilson explained that he had been unable to leave for fear of being captured by immigration. The doctor ignored this, gave him a couple more scoldings and left. Then a nurse came and threw a package at Pastor Wilson.

"You are responsible for him. Undress him and put this cap and gown on him. He is now going to be treated," she said.

Pastor Wilson began to slowly remove his clothes, which by now were melting into his skin. Wikey clenched his teeth, opened his eyes and flailed his arms in an agonising struggle, as if, possessed by pain, he did not recognise his benefactor. But then the pastor whispered in his ear, told him about a different future, said nice things to him in Creole. He seemed to be humming a song softly to him. He managed to calm him down and the clothes began to give way, coming off very slowly, the pastor going centimetre by centimetre, and although he did so carefully, tearing the fabric was also tearing away part of Wikey.

Fabric and skin had become one, but Wikey looked at him calmly, listened to him and seemed to follow the thread of the beautiful story. He seemed to believe him. I suppose that's what kindness looks like: in the midst of horror, a person singing softly and promising good things while changing the clothes of a man who has been skinned alive.

***

After the night the police killed Gems Joacin, the pastor takes me near the Fuisa neighbourhood to meet Mikelson.

We arrive at a hill where this week Haitians, fed up with the harassment of the uniformed men, threw a storm of stones at the patrol cars. The army had to come to get those police officers out of there. In the cuarterías, places where Haitians rent small temporary rooms to live in, there is an air of alertness. The authorities' hunt has been so overwhelming that the Haitians leave their windows open so they can escape across the rooftops in case of a raid.

We drive around the neighbourhood several times, Pastor Wilson greeting everyone. We stop at a two-storey shanty and knock on a tin door. A young man comes out half-dressed, his face covered in paint residue. The pastor asks him something, the man points to another tin shack, and the pastor scolds him. The man hurries away, unlocks a door and comes out carrying a baby girl.

I'm not good at guessing the age of children, but this one is less than a year old. Her mother was kidnapped in the second week of October on the streets of Verón, Punta Cana. She was taken to one of the prisons that serve as a holding place before deportation. She left the baby in her shack and begged the officers to deport them together, but to no avail.

Pastor Wilson found out and went to get the girl, who stayed at his house, where he lives with his wife and children, for several nights before handing her over to the woman's neighbours.

"How many babies have you had to take in so far this year?" I ask the pastor.

"Hmm, several, Juan, several," he replies with a sad smile.

"Will that be about four?" I ask after doing a calculation that is already horrifying to me. But the pastor jumps up like a spring.

"Four? Are you crazy?"

Pastor Wilson says he has had to take in at least 25 children under the age of ten since the start of the year.

The boy with paint on his face does not know the baby's name or how old she is, nor does he know the mother's name or if she will return. The pastor reassures him, telling him that he has managed to get the mother released and hopes that they will be reunited. In the meantime, the underground railway, a semi-clandestine network of Haitian leaders and organisations resisting apartheid, will take care of her.

We then go to another neighbourhood and then another in search of Mikelson. The stories seem endless and the leaders do not want to miss the opportunity for a journalist to document the tragedies in their neighbourhoods. There is the case of the woman who was taken from the hospital on the same day she had a caesarean section and had to hide from immigration in her shack with her baby for a week, with talcum powder as her only medicine. There is the case of the man who had to hide in a hole filled with glass bottles and whose body was left looking as if it had been bitten by a thousand piranhas.

We finally arrive at a building that serves as a boarding house, and a man comes out with both legs in plaster casts. This was the result of being thrown from a great height by an immigration officer.

"Bonjour, Mikelson, je vous cherchais. C'est un plaisir," I say, my rehearsed line with the worst pronunciation French has ever heard since it was invented.

He greets me very kindly, but his name is not Mikelson, my man on the roof. His tragedy, which will keep him out of work for at least six months, was not recorded by anyone.

At this point, I begin to believe that this underground railway, this vast network of Haitian leaders, may indeed know who Mikelson is and where he is, but that what matters to them is showing me the horror of apartheid. Or maybe not, maybe there are just too many Mikelsons in the Dominican Republic.

***

Gems Joacin rests where those who die should rest. He is in a very simple wooden coffin, which the pastor managed to buy with help from his parishioners and money from his own pocket. The police had to return the body and there will be an investigation into the case. The vast majority of these investigations come to nothing, but at least there will be a record and, above all, he was not thrown into a ditch in the middle of cane rubbish.

In the last week of October, Pastor Wilson, his team of leaders and some people from the neighbourhood say goodbye to Gems Joacin with a song. It is a sad song, as if from afar. They sing it slowly, lengthening the vowels and with a rhythm reminiscent of the ritual songs of some African societies.

"Come to him, come to him. Come to him. Your great saviour is waiting for you, come to him..."

Funeral of Gems Joacin, who was killed by the police.

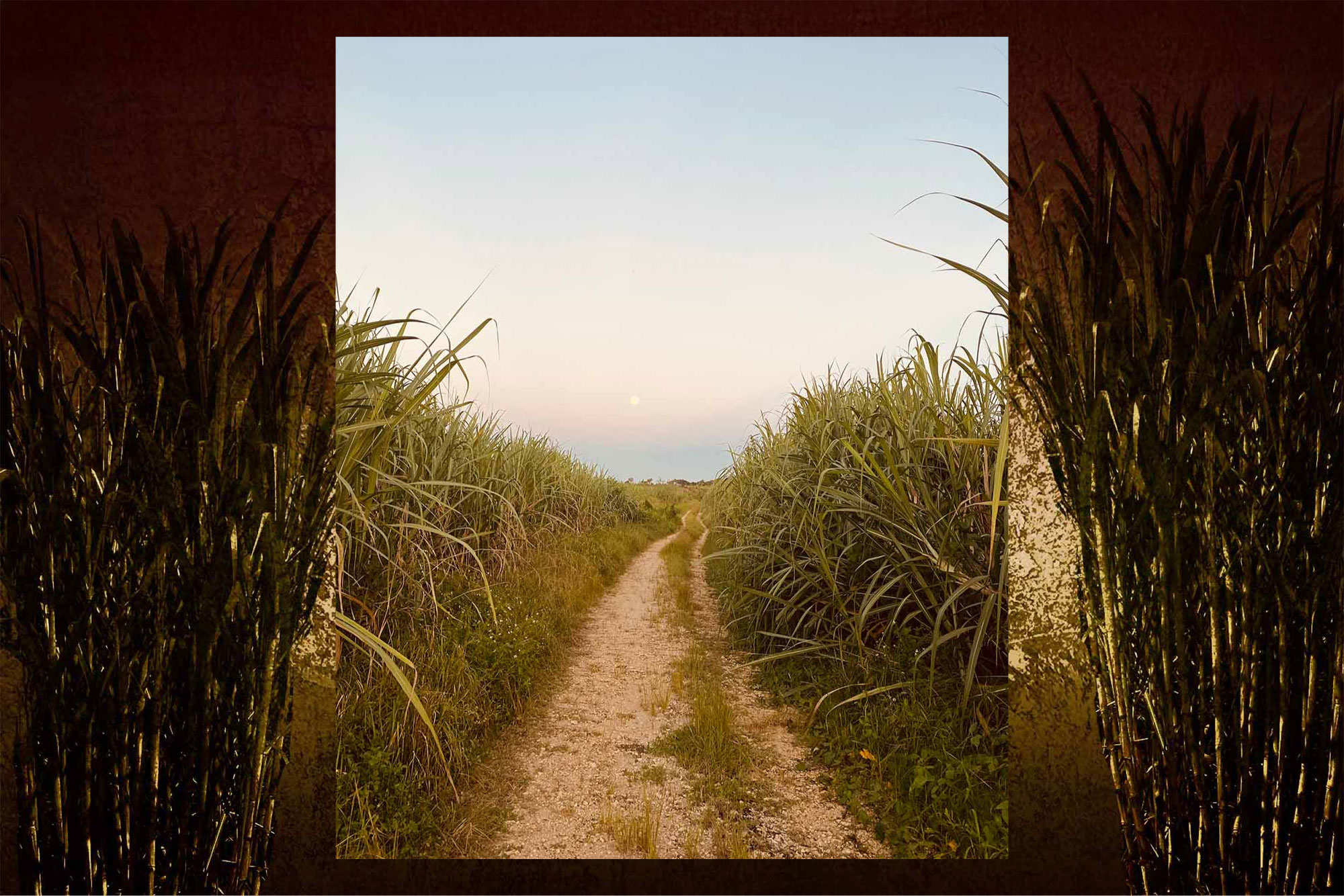

The melody reminds me of another song, the one sung by the wind over the endless fields of green cane. It evokes another time, reminding me of the good things that still dwell in the human soul.

The pastor tells me to get ready, that tomorrow he will take me to see Mikelson. I no longer know if that man will only be remembered as the person a chronicler never found. Without meaning to, he already showed me so much.

***

Part III: Mikelson's Open Window

We cross a small yellow dirt road and suddenly everything disappears. A green wall about two metres high, very dense, creates a kind of tunnel on both sides. All around us is sugar cane. During Gems Joacin's funeral, the melody of the wind in the cane fields seemed gentle to me, but now I feel it is a more melancholic music, like something from another time.

Pastor Wilson tells me that if you were to "sail" across this kind of green sea, it would be possible to cross the 200 kilometres or so that separate Punta Cana from Santo Domingo.

It is our penultimate meeting and we set off in the morning with the promise of finding Mikelson. I'm surprised we're looking for him here, because one of the few clear things in the blurry video that has obsessed me for almost a month is that the policeman throws Mikelson off a rooftop in an urban neighbourhood. But I don't say anything to the pastor. I think my guide wants to show me something else, the source of all the ills of the Haitian community, which has to do with sweetening the world for others.

In 2024, sugar cane is still cut and processed with machetes and muscle power, as it was in colonial times, when the French and Spanish ruled the island. Sugar cane is still one of the economic activities that requires the most Haitian labour in the Dominican Republic.

During the colonial era, slaves lived in bateyes, ghettos of shacks where they never mixed with Dominicans (batey is a word from the Taíno language, which referred to a ball game, but when the Europeans exterminated these indigenous people, it came to refer to these homes of agricultural workers). The plantations passed from the hands of the colonists to the Dominican State, and then the large transnational companies arrived, such as Central La Romana, the largest of all, owned by the Fanjul brothers, a family of Cuban origin that has created a sugar empire from Florida. The conditions for Haitians, however, have changed little.

In September 2022, the US government, through the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency, issued a detention order to prevent all ships carrying sugar or sugar derivatives from Central La Romana from entering the country. Investigations by various international entities found five of the 11 indicators established by the International Labour Organisation to determine that conditions in a place are unacceptable and abusive for workers. Central La Romana denied the accusations of the US investigators, who detected everything from child labour to forced labour in their investigation, modern words to describe something very similar to that great curse of the Haitian people: slavery.

We arrived at Batey la Romanita, a kind of island of trees that breaks the monotony of the green sea. A group of children were playing football on a piece of land.

"Look, Juan, there's Real Madrid," Pastor Wilson said to me, laughing loudly.

The batey is in a state of lethargy. Several men squatting on the ground stare at us, and some women emerge from the 14 faded barracks. An old man waves us over, speaking softly in a mixture of Spanish and French.

He tells us, his mouth moving as if chewing, that after 53 years of working in the batey, he has not been paid his pension. Officially, cane workers earn 15,000 pesos a month, equivalent to 283 US dollars.

However, there is not enough work all year round and they are often paid according to the weight of the cane they cut. With this pay, it is very difficult to save for old age. Without a pension, these people are at the mercy of the batey and its inhabitants, and at the mercy of the company and apartheid.

A group of elderly people vegetating in the shade of an old barracks tell me that Central La Romana fired them. A very old woman asks me for some money for food and shows me with a pitiful smile that she lost her teeth some time ago. Another woman begs Pastor Wilson for help. She tells him that her husband died after working for more than 40 years in the cane fields. She says that company representatives have visited her and told her that she may have to leave, as the house she has lived in all her life may be needed for new workers.

The scene has a ghostly air, but everything indicates that I won't find Mikelson here, the ghost I've been looking for for a month. Suddenly, I see a kind of apparition.

A brand-new bus speeds down the street in front of the batey, leaving a trail of yellow dust behind it. When I ask the Haitians who is on the bus and where they are going or where they are coming from, they seem to have forgotten their Spanish. In Creole, they tell Pastor Wilson that they are Americans.

I ask him to insist, and he only manages to get two words out of them, "Americans" and "voodoo."

***

One night in August 1791, as a thunderstorm raged in the sky, a mambo or voodoo priestess named Fatiman called out to the African loas above and to the guede, the ancestral dead, below. The hands of black men and women beat drums like thunder in a place near Cap Francais, now Cap-Haïtien, on the French side of Hispaniola. It was on that night that the slave system began to die.

Hundreds of black slaves fled the plantations and gathered in a remote place in the mountains, a place where the now-extinct Taínos, murdered by the Spanish and the plagues they brought with them, worshipped the gods who died with them. The place was called Bwa Kayiman, or Bois Caimán, which could be translated as "forest of the caimans".

The ceremony was led by Mambo Fatiman and Dutty Bokman, one of the heroes of Haitian independence. A freed slave who had arrived from Jamaica and, steeped in French ideas of liberty and equality among people, soon led this large, angry mass of kidnapped Africans and their descendants.

That night, Mambo Fatiman sacrificed a black pig and those present drank its blood and swore to destroy the white masters. Historical tradition says that the loas came down from a large tree. Papa Legba opened the pantheon and then Shango, Debehlla, Achun came down, as well as Ogun, the lord of war and iron, and Loko, the lord of the forests and trees. The loas were accompanied by an army of guedes, the dead ancestors. That crowd, feeling the power of those offended gods who had travelled with them from Africa on European ships, threw themselves with machetes and daggers in hand onto the sugar cane plantations.

Not all the slaves came from the same places, nor did they speak the same languages, but their ritual practices were similar and their gods referred to the same religious universe. Thus they understood each other. To the beat of the drum. On that night in August 1791, in one of the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean, thousands of slaves put to the sword those who had stolen their freedom, those who had tried to turn them into animals.

***

I return to the sugar cane plantations to unravel the mystery of the white bus. This time I travel alone. The endless green sea and the shells of old trucks play with my mind and I feel as if I have travelled back in time, to an ethereal, desolate past.

I ask about the Americans and voodoo, the two words that were mentioned to Pastor Wilson the other day. I ask with confidence, as if I know what I'm talking about, even though I have no idea.

The answers lead me to the back of a new batey. I come across an old cockfighting ring that looks abandoned, where four near-skeletal children are now playfighting. There are a few wooden houses with dilapidated tin roofs. Several young men approach me. I say the same two words to them, and one looks at a watch on his wrist.

"Almost, they'll be here at three," one of them tells me, pointing to one of the wooden shacks painted red and black. I knock on the door and an old man appears. Inside there are ritual drums, candles, cans of baby powder, machetes and bottles of liquor. It is a voodoo altar, or so it seems.

The old man tells me I have to wait for the owner. While we wait, a small group of curious people gather to get a closer look at the stranger who has arrived asking questions. They tell me that leaving the batey is very dangerous now that the deportations have intensified. Several people have gone out to buy food and never returned.

I ask them about their daily food, and they tell me that the diet in the batey is limited to cassava, rice and plantains. Never all three together. I ask an elderly woman if they eat this monotonous diet three times a day, and she looks at me with a mixture of indignation and anger.

"Three times a day? We eat once a day!"

At that moment, a van appears. It looks as out of place as a refrigerator in a desert. Margarita the witch gets out and introduces herself. She is a small Dominican woman of about 50. At first she is hostile, but she calms down when I tell her I am a journalist interested in voodoo. After a chat and some suspicious questions, she invites me into the red and black room.

Margarita tells me that this house is hers and that she organises a voodoo show for foreign tourists every day. She tells me that she charges 150 dollars a day to organise the show and that she gives a few pesos to a group of bateyanos to play drums and put on the show.

She tells me that the real business isn't hers; she's subcontracted by a German named Norbert. He organises tours for Europeans and North Americans. He takes them to beaches, restaurants and a river. At three o'clock in the afternoon, he brings them here with the promise that he will show them something unique, rarely seen by white people: an authentic voodoo ritual taking place that very day.

Shortly before that time, a jeep appears. It is Margarita’s daughter, a beautiful brunette with full lips, dressed in jeans and a belly-baring top. She has very eye-catching tattoos on her hips and neck.

We talk about the outfits she will wear in the show. She tells me that she chooses them herself, according to her own criteria. Her mother scolds her and tells her to change quickly because the tourists are about to arrive. She returns in costume, looking like a mishmash of symbols with a handful of necklaces, bracelets and scarves. Her mother lights candles and sets up chairs.

Three elderly Bateyan men take their places in front of large drums, and one of them dresses up as Bokó, in the same style as the girl.

"Let's say you're my nephew because Norbert is going to ask me. Remember, this is his business," says the witch, placing me next to her, behind the men and the drums.

At the house of "Witch Margarita", preparations are underway for the voodoo ceremony that will be held for tourists.

The white bus arrives on time. There are about 50 tourists. They are all white and dressed for the beach. Norbert is a man in his 70s. He is bald and dressed in a red shirt, brown shorts and beach sandals.

The five men begin to beat the drums to set the mood and the tourists sit down on the benches, taking photos and videos of the scene. The officiants are five bateyanos. Three are elderly men who were dismissed by the sugar cane company without compensation, and the others are young, burly men who beat a monotonous rhythm on the drums.

Norbert begins to explain in German and French, and the tourists nod and open their mouths in surprise. He directs the event as if he were a bokó himself and snatches a pair of maracas from an elderly man's hands and plays them for his customers.

In the middle, a fire burns and Margarita’s daughter moves in a chaotic dance, as if in a trance, pretending to be mounted by a loa. Norbert invites the tourists to play the drums and maracas themselves. Then those white people, still with sand in their sandals, dance without any sense of rhythm, dancing and playing the drums.

As I watch the scene, I remember the bokó Winston Pierre, the voodoo priest who gave me a master class in Haitian history and who patiently explained to me the "biographies" of a dozen African loas. He wouldn't even let me take pictures of his fetishes for fear of offending those loas. I also remember the more than ten bokós and ungans that Moisés, my first guide on the Haitian underground railway, took me to visit. They bring their fetishes from Haiti in coffins, hidden from the Dominican police among merchandise, and they do not allow even their own relatives to approach them.

At that time, at the beginning of this investigation, I hoped that this part of the railway, perhaps the most hidden of all, would lead me to Mikelson. Voodoo, like many religions of African origin, has been a practice of resistance, a way of bringing their home with them wherever they went, and a way of being strong in something that chains cannot capture, and it continues to be so in this new apartheid. According to the Constitution of the Dominican Republic, there is freedom of worship, but in practice the state persecutes voodoo as part of its persecution of everything Haitian.

"Police dismantle shack used by Haitian nationals for witchcraft and sorcery in Cabarete, Puerto Plata," the official website of the national police reported on September 12, 2023. According to the same publication, "the witch doctor" Papallo kept the neighbourhood's inhabitants in a constant state of anxiety with his rituals.

In March of this year, the police uploaded a video to Instagram and X showing them dismantling an altar. The person recording the video is shocked when he pulls out two coffins used for ritual purposes.

"This looks like a cemetery," he says.

After destroying the hut and taking everything out onto the street, the officers set it on fire.

"We're not setting fire to the house because the witch doctor's children are inside," says one of the police officers, while in the background a group of black children watch fearfully as their father's sacred belongings burn.

According to Simón Rodríguez, a Venezuelan journalist based in the Dominican Republic, persecuting Haitian voodoo is one of the pillars of Dominican identity and another way of creating distance between "us and them."

During the Trujillo dictatorship, a law was passed that expressly prohibited the practice of voodoo in Dominican territory. This law — although freedom of worship is enshrined in the constitution — remains in force, and attempts to repeal it have been met with opposition from both the evangelical community and various political factions.

After an hour of suffocating heat, the exhausted elders of the batey stop playing their drums and the cheerful European holidaymakers finally stop the frenetic, rhythmless movements that they call dancing.

For a moment, I feel like speaking up and telling them how lucky they are that these people need their pennies so badly, telling them that 233 years ago, on this very island, thousands of people like these old folks hacked people very much like themselves to pieces. I would like to tell them that the reasons are similar: they wanted to kill their culture and their freedom. Those with whips and chains; these with money.

But I don't. I rush out to my truck. The mystery of the white bus is solved: everything seems to indicate that the problem isn't voodoo, but rather who practises it, who dances it.

I'm here looking for something else.

***

It’s the morning of October 26, 2024 and Pastor Wilson drives his lopsided truck. He seems cheerful, even though every day this man has to deal with complaints and calls for help from the Haitian population in this beautiful corner of the island. I've only been working on this investigation for a little over a month, and I already feel the overwhelming weight of dozens of messages and calls from desperate people. They call to tell me about some horror, asking for help that is often impossible to give them. They send terrible videos showing black men and women lying on the ground, being beaten, caged or screaming in rage in the chilling Haina Holiday Resort. Always suffering, always losing. These videos and complaints will continue to arrive on my phone even after I leave this island, each time more graphic than the last.

Pastor Wilson himself will be arrested by the police in two day times. A group of uniformed men will arrive at his home at 11 pm on 28 October and take him away in handcuffs in front of his children. He will spend the night in uncertainty in a cell and will be released in the morning because, as he will later say, he was accused of an unspecified fraud.

On the day of his release, he will receive death threats and consider fleeing Punta Cana. He will not do so, however, as the underground railway that protects Haitians as best it can must continue to operate, always in the shadows, always losing everything, always gaining very little.

This is my last day reporting in the Dominican Republic, and I have given up trying to persuade the pastor to take me to Mikelson, the man thrown from a rooftop by a police officer. His tragedy came to me in the form of a video a few days before I arrived in this country.

It became an obsession. I thought it would be as scandalous as the video showing Rodney King being almost killed, or the one showing a police officer suffocating George Floyd. "I can't breathe," he said.

Los Angeles burned for Rodney King in 1992, and the United States trembled for Floyd in 2020. Not for Mikelson. There will be no streets taken over, no cars set on fire, no headlines. Perhaps, in the eyes of the world, not all people are equal. Perhaps my obsession with finding this man will prove futile in a country where hundreds of thousands are Mikelsons. I looked for a drop, then realised I was looking for it in the sea.

Today, once again, I let myself get carried away. Today Pastor Wilson is smiling, and his smile is contagious. He is happy because he managed to get a hospital to give him a back brace for a man with broken ribs. Amidst so much tragedy, this tough man has learned to find joy in the small victories of those who always lose: saving a girl from death after her mother was deported, getting medicine to cure an infected caesarean section, getting a place in the hospital for a man who was skinned alive, managing to bury a man who was murdered in a cemetery.

Along the way, he tells me that he doesn't understand why his people are so hated in this country, given that they are the ones who have historically produced its wealth, whether in the sugar cane fields, the coffee plantations, the tobacco fields, the textile factories or building hotels in Punta Cana.

Several days ago, while we were searching for Gems Joacin's body in the Matamosquito neighbourhood, one of his collaborators told me, "It's as if we had raised a lion cub, giving it the best milk, and now it's coming after us to eat us."

We entered the dirt alleys of a neighbourhood near Matamosquitos. In one of the wooden and tin houses on the side, the man who Pastor Wilson had brought the orthopaedic brace for was waiting for us.

"Juan, meet Mikelson!" he says enthusiastically as he puts his thick hand on the boy's shoulder.

Mikelson, the 19-year-old Haitian man who was thrown off a rooftop by a police officer. In the video, he explains what happened that morning.

Mikelson has a frightened expression, but still retains that sparkle in his eyes that children have. He is only 19 years old. In one hand, he holds the same vest he was wearing when, in early October 2024, Dominican police officers threw him off a rooftop. He does not speak Spanish, so Pastor Wilson has to translate.

That day, Mikelson was getting ready to go to a hotel construction site in the tourist area of Punta Cana and had already put on his reflective vest when he heard screams. Several trucks were hunting down Haitians in the neighbourhood. He heard them kicking down the door of his tin room.

The entire room shook, and he opened a wooden window next to his bed to escape. He climbed out, alongside other Haitians, and they began to climb. They managed to get onto the roof, but behind them a policeman also climbed up.

"Catch him, catch him!" Mikelson remembers the officers shouting from below.

The policeman caught his neighbour, who managed to slip out of his hands and jump onto another roof. Mikelson couldn't make it; he was trapped between the edge of the roof and the policeman.

"Throw him down, throw the Haitian down!" shouted the policemen below, so the uniformed officer grabbed him by the neck and belt and threw him down.

While this was happening, a woman recorded everything while crying and shouting, "Baba, baba, they killed him!"

What she didn't record was that between the roof and the ground there was a tangle of loose electrical cables. Mikelson fell onto them, slowing his fall. Then came the impact with the ground. He was unconscious. The police left him there and drove away.

His neighbours picked him up, washed his face and immobilised his back. They contacted a pastor named Wilson, and he managed to get him to a hospital and save his life. The woman in the video passed it on to an acquaintance, who passed it on to another, and so on until it reached the eyes of the writer of this article.

Mikelson was born in a village near the Artibonito River in southern Haiti. He came alone, without his family and without knowing anyone, to work in this country a year ago. Other compatriots told him that in the Punta Cana area, Dominicans hire Haitians regardless of their immigration status. Mikelson came, like thousands of other Mikelsons, to work in the Dominican Republic while the police hunt them down.

Mikelson walks bent over, with several broken ribs and a host of less serious but equally painful injuries. From now on, it will be even more difficult for him to build hotels in this southern part of the island of Hispaniola, where the last system of racial segregation in the Antilles tightens its grip on a poor and desperate population. The policeman who threw him off a roof destroyed the only tool he has in life: his body. The screws are still tightening. The train keeps rolling. Mikelson sleeps every night with the window open.

“This investigation is a production of Redacción Regional and Dromómanos, and was originally published in December 2024 thanks to the support of the Consortium to Support Regional Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR), led by the Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR).”

Illustrations: Donají Marcial

Images and videos: Juan Martínez

Journalism mentoring: IWPR

Editing: Dromómanos - Redacción Regional