Cuban Journalists Face "War of Attrition"

Conference hears how writers who reject the state-controlled press face harsh consequences.

Cuban Journalists Face "War of Attrition"

Conference hears how writers who reject the state-controlled press face harsh consequences.

A Cuban journalist has described “a war of attrition” against independent media by the Havana regime, despite the positive potential of new and emerging digital platforms.

Carlos Alejandro Rodríguez Martínez previously worked for two years as a journalist for the official Communist Party’s weekly newspaper Vanguardia in the island’s Villa Clara province.

He told fellow journalists at the Latin American Digital Media and Journalism Forum that writers like him who broke away from the state-controlled press faced potentially harsh consequences.

Rodríguez left Vanguardia in July 2017 after his managers at the newspaper hacked his personal Facebook account and his email. A month later they prevented him from leaving the country when he tried to take a flight from Havana airport.

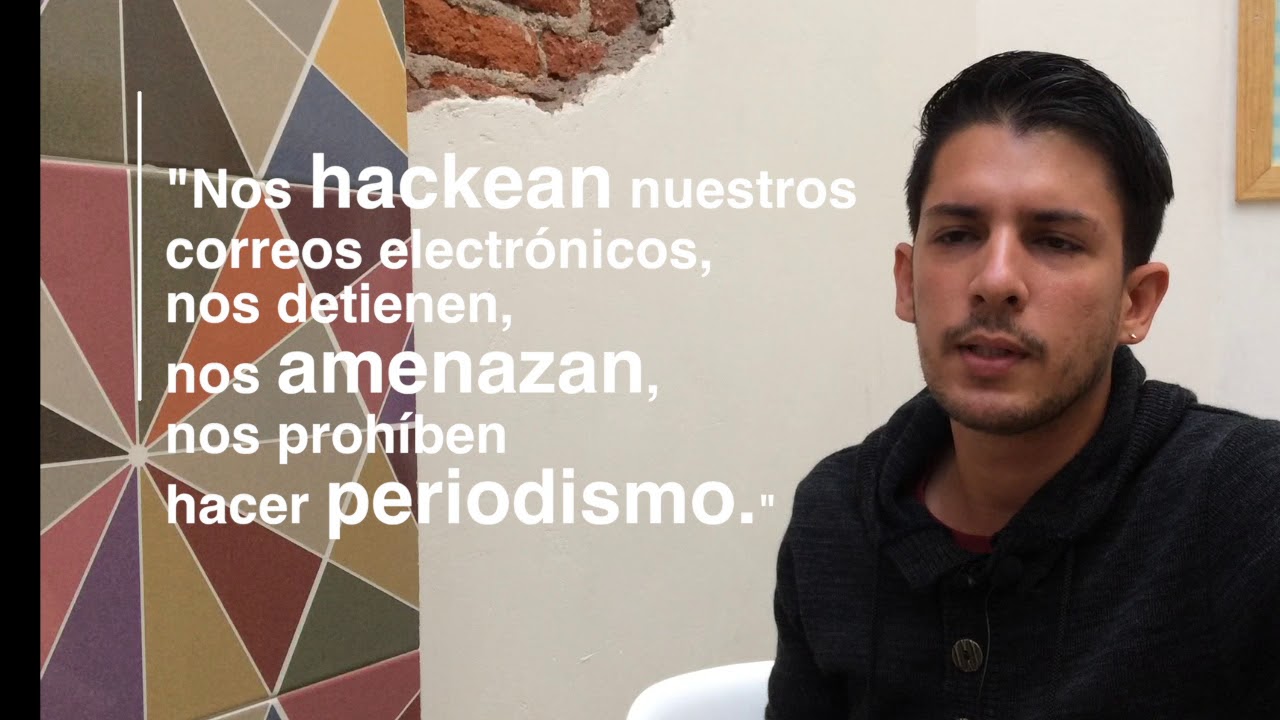

“In Cuba there is a war of attrition against journalists who attempt to exercise their profession outside of state control. They hack our emails, prevent us from leaving the country with no explanation, stop us from exercising our profession, threaten us, and ban us from doing journalism,” Rodríguez said.

The government “controls all of the information around us,” he continued. “They carry out smear campaigns where we live. The panorama in Cuba is very different from the rest of Latin America. Our reality is more comparable to the context of the press in China than that of our own continent,” he told delegates at the November 2017 conference.

According to Reporters Without Borders, Cuba holds 173rd place out of 180 nations in the World Press Freedom Index.

The 1976 Cuban Constitution states that the right to freedom of press and speech must be “in keeping with the objectives of a socialist society”. This means that producing material that challenges the state may be punishable by a prison sentence of between three months to 15 years.

Rodríguez, a graduate of the Central University of Santa Clara, said that the Cuban government was also using more subtle harassment to control the media.

In October 2016 Rodríguez was among a group of reporters who was detained in Baracoa in eastern Cuba while attempting to report on Hurricane Matthew. More recently, Rodríguez was detained in Villa Clara’s Isabela de Sagua while reporting on evacuations in the area resulting from Hurricane Irma.

“The government’s current tactic is not so much combatting what is published in this media but rather discrediting the professionals who produce it,” he said. “Some journalists have been forced to leave Cuba, others continue to work there but are harassed. Cuban journalists whose freedom of expression has been limited have no institution that they can turn to; the authorities do not provide explanations. Journalists who decide to be independent face very negative circumstances.”

But the Mexico City conference also heard that the appearance of new digital outlets, facilitated by increased internet access in Cuba, was helping to change the country’s media landscape.

Rodríguez has written for independent media in Cuba including El Estornudo and Periodismo de Barrio, which along with outlets such as El Toque and Play Off Magazine are opening up the island to the wider Latin American context.

Jordy Meléndez, the organiser of the forum, said that it was vital for Cubans to be able to share their experiences.

“We have been holding this event for six years and it is the first time that we have managed to have a Cuban journalist at our roundtables, in our conferences,” he said. “I think it is absolutely essential to hear the voice of the Cuban people. There is generalised violence against the press. But countries like Mexico, Venezuela and Cuba are facing twice the challenge.”

Juan Manuel Casanueva, the founder of digital research NGO Social Tic, agreed that Cuban participation in the forum was particularly important.

“Firstly, it was significant because we must cover different kinds of contexts in digital media, not just cities where the majority of people are connected, but also in spaces where there are technological restrictions,” he said. “And secondly, because it is so important to have a complete Latin American vision and that includes Cuba. While the forum has been very diverse for a long time, Cuba has been missing.”

The digital space gave Cuba the opportunity to return to a wider debate on regional media, Meléndez continued.

“We’d like to learn a lot from the Cuban journalists, from the projects they are creating and developing on the island,” he continued. “Cuba’s presence in this forum is something we’d like to repeat; we don’t want this to be the only occasion. We need more connections, more conversations,” he concluded.