Central Asia: Fighting, Inside and Outside the Ring

Women who dream of taking on combat disciplines have to first defy conservative traditions.

When Shoira Zulkaynarova saw the comment, reading, “Give up boxing, you’re cursed!” on her Instagram page, she just shrugged. Unpleasant as it was, Tajikistan’s eight-time boxing champion would not allow haters to get in the way of her sporting passion.

The 28-year-old is one of a rising generation of athletes in Central Asia defying patriarchal norms that see sports, and combat disciplines in particular, as unsuitable for women.

Gender equality is enshrined in the constitutions of each Central Asian country. The former Soviet republics have ratified all major international conventions promoting women’s inclusion and rights and translated them into their national laws.

Conservative social norms, however, are harder to dismantle.

As he inaugurated a new school in Bishkek in September last year, Kyrgyzstan’s prime minister Akylbek Japarov said that “girls must learn to be the housewife, and boys must learn to earn money, defend their homeland”. His comment drew online criticism but reflects common views about the role of women, who remain largely out of decision-making circles at the national level, have limited access to skilled jobs and often marry at a young age.

Sports remain largely frowned upon and girls who dream of taking on combat disciplines find the first obstacles within their own families. Some, however, have started breaking that glass ceiling.

Kazakstan: Natalia Tsoi, boxing referee

“Women, move as a butterfly, sting as a bee”

Katerina Afanasieva

Natalia Tsoi first walked into a gym when she was five years old - to learn ballroom dancing. It was not quite the martial arts she dreamt of, but girls and combat sports were a contradiction in terms in 1980s’ Soviet Kazakstan.

Fast forward nearly four decades and the now 42-year-old has a set of awards under her belt, none of them for dancing. Tsoi became Kazakstan’s first female boxing champion and an official judge of the International Boxing Association (IBA); she was one of only four female boxing referees at the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. In her private life she is a police captain, a PHD candidate in law and mother to two girls.

“I feel myself to be in the right place, and I am so happy.”

It has been a long and at times rocky journey. Determined to learn martial arts, Tsoi took taekwondo in high school, becoming Kazakstan’s champion. She then switched to kickboxing.

“Boxing was the most male sport for me. I had never thought about it. There were no female boxers in Kazakstan, it seemed something out of reach,” she told IWPR. With neither state nor private support for women’s boxing available, she decided to focus on finding a job and joined the police.

Within a year she was back in the world of sport, taking up boxing and joining Kazakstan’s first women’s squad. In 2006 Tsoi became the country’s first champion.

“You have to think a lot when you are out in the ring, and you need to have a high-speed mind not to miss a beat,” she said, adding that while not every woman needs to become a boxer, learning self-defence is essential.

One evening, as a second-year student at the police academy, she was ambushed by a middle-aged man, sober, in decent clothes: he dragged her towards a car. There was no one around. She took off her fur mittens and hit the stranger in the face. In a split second he was on the ground, knocked out.

“I have never knocked out anyone before. God and my combat skills saved my life,” she recalled, adding how she then ran home, in fear. For years, Tsoi never told the story to anyone. “There are so many bad men around that you need to be able to protect yourself and your children.”

Women’s boxing is gathering pace in Kazakstan, albeit slowly as costs and social pressure exclude girls from the arena.

“At first people wondered [about me], then they admired me. Someone might have criticised me, but they never said it straight out. They were afraid,” Tsoi said..

She had no plans to become a referee. The first invite came by chance, in her native Karaganda, a town about 200 kilometres south-east of Astana, and it eventually became her profession.

“I have never felt any negative feelings from boxers. On the contrary, women are more fair, there is a strong sense of responsibility in what they do.”

Looking back, she said she was lucky that her parents supported her. She learnt to kickbox from her dad, a martial art aficionado. Her mother soon abandoned the idea of a dancing daughter and once told Tsoi, “If it’s your path, you will find the right place.”

“I feel myself to be in the right place, and I am so happy,” she said.

Kyrgyzstan: Farida Abdueva, Muay Thai fighter

“If there’s a will, there’s a result”

Aigerim Konurbaeva

Muay Thai is not for the faint of heart. Thailand’s national sport, also known as Thai boxing, is characterised by the combined use of fists, elbows, knees and shins, hence the label “the art of eight limbs.”

Nineteen-year-old Farida Abdueva is a master. She first fell in love with the martial art when she watched her brother practice; at 14, she told her parents that she wanted to start training and eventually competing. But her parents did not take her seriously.

"The main thing is not to give up after you lose, even if it’s hard.”

“They did not take me seriously, thinking I would quit in a month or two,” Abdueva told IWPR. “But I set my goals clearly and started to train hard from the very first days.”

Steadily she climbed the ladder, competing nationally and internationally, collecting medals along the way.

“I have participated in tournaments in Uzbekistan, Jordan, Kazakhstan and Thailand,” Abdueva said. “In 2022, I won first place and got my first belt in a Muay Thai competition. Then I became the champion in two divisions in the Asian MMA Championship.”

Muay Thai international tournaments are only held twice a year, so Abdueva has also embraced mixed martial arts, known as MMA, Wushu Sanda, Burmese boxing, Kung Fu and boxing,

Combat sports are demanding physically and psychologically. Sometimes your body just freezes, she said.

“It stops obeying your commands. Training is hard work, behind every match there are long hours spent in the gym; no one sees [that]. Only my trainer and I know the price of each victory. But if there’s a will, there’s a result, despite the difficulties. The main thing is not to give up after you lose, even if it’s hard,” Abdueva said.

If social norms keep girls away from sports like Mauy Thai, the lack of financial support is another deterrent.

“It is expensive. Athletes need money for healthy [food and] vitamins, for participating in competitions and gaining experience, for attending training camps in other countries.” Unfortunately, the state supports Olympic disciplines only. Abdueva and her trainer Alexander Kononenko regularly crowdfund to raise the money to enter competitions.

“I have a feeling that our country does not take women’s martial arts seriously, but we also represent our country, we also raise our flag in foreign arenas. I think that women competing in martial arts deserve scholarships, good attitudes and recognition just like other athletes.”

Tajikistan. Shoira Zulkaynarova, boxer

Each punch is full of dreams

Farzonai Umarali

Her head wrapped in a hijab and her hands encased in thick boxing gloves, 28-year-old Shoira Zulkaynarova is Tajikistan’s eight-time boxing champion and has been standing up for herself ever since she chose the discipline.

“Negative comments pour in every day,” she told IWPR. “‘You're a girl, what do you need sports for?’, ‘Get married, start a family!’, or ‘Why did you even choose boxing, were there no different professions out there?’. At one stage I quit and stopped training for almost a month, but I got back on the path to achieving my dream.”

She recalls participating in an international championship in 2019 and defeating her first two opponents. However, no one, including her coach, thought she could beat her last, more experienced, adversary.

“Negative comments pour in every day.”

“’He told me ‘You will lose, she is very experienced.’ I replied that that my sports ethic would not allow me to drop out. I went into the ring and I won,” Zulkaynarova said.

Most recently, in December 2022, she won a bronze medal in an international tournament where she competed with an arm injury.

In Tajikistan, families often prevent girls from engaging with sports, in particular combat like boxing. Money is also an issue.

“My brothers have been supporting me a lot [from the beginning]. They used to take care of all financial matters, which means I participated in competitions abroad at my own expense. Since 2020 the government started supporting athletes, and I could not be happier,” she said smiling.

As for future ambitions, Zulkaynarova is clear - “Representing my country at the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.”

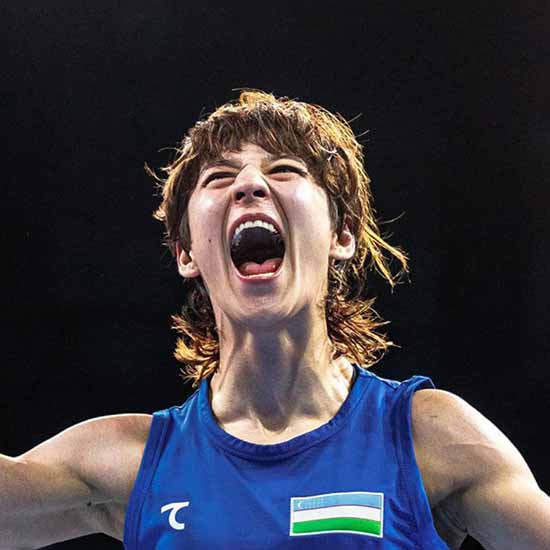

Uzbekistan: Aziza Yakubova, boxer

Breaking Records, in Boxing and Society

Elina Beknazarova

At 29, Aziza Yakubova is Uzbekistan’s first female boxer to stand on an international podium, The bronze medal she won at the 2022 world championship in Turkey, in the under 55kg category, inspired a host of other young women: six months later in January 2023, at the Asian Youth Championship held in Tashkent, Uzbek female boxers won ten medals, half of which were gold. All the athletes were under the age of 22.

Born in Jizzakh, in the country’s south-east, Yakubova credits her boxing career to her uncle Gairat Karimov: himself a boxer, he took her to a gym when she was six years old and coached her for nearly a decade. In 2009, age 15, she had to stop to follow her mother who migrated to Russia for work. For five years, both worked in various jobs to make ends meet.

“[It] is not just a sport, it is something I live and breathe for.”

The 2016 Olympic Games bought revamped her passion. In Rio de Janeiro Uzbek male boxers won seven medals, including three gold. Hasanboi Dusmatov became a star in the discipline, a hero in Uzbekistan, and Yakubova’s idol.

“When I watched our boxers sparring and saw their victories, I told my mother, ‘Mum, I want to be a boxer,’” she told IWPR.

In 2019, she moved to Andijan, 350 kilometres south-east of the capital Tashkent, and started training with Ziyatdinbek Toigonbaev, Dusmatov’s former coach, who also helped her find work with the local boxing federation.

Her mother, Suriyakhon Karimova, has supported her every step of the way, ignoring sexist comments and pressure to convince her to quit boxing because it “was not suitable for a girl.

“[It] is not just a sport, it is something I live and breathe for,” Yakubova stressed. “I want to reach all the best results in amateur boxing and then become a professional athlete.”

She remains adamant that if you want, you can, even amid the conservative and rigid norm of Uzbek society, become a champion.

“Sport is about dedication and hard work. The main thing is to set your goal and remain focused to reach it, despite what other people say,” Yakubova said, adding that her dream is to open her own boxing gym and train Uzbekistan’s future female boxers.