Battle Rages in Fortress Bakhmut

Russian troops are determined to gain control of the eastern city that has become a key political prize.

I meet Andrii and Serhii at the entrance of a burnt-out high-rise building, one of the many looming over the ruins of Bakhmut. They drive an infantry fighting vehicle (IFV), the only transport left available in the eastern city that Russian forces and mercenaries have pulverised in their determined effort to control it.

Shelling is all around us, and drones drop artillery from above. Yet the two wear no body armour or helmets, only waxed jackets. Andrii’s has a tear on the back.

Six months ago, he was a welder and Serhii was a train driver. Now they are the most celebrated IFV crew of the Ukrainian army’s 93rd Mechanised Brigade in Bakhmut. Recently, they drove their IFV close to the enemy’s position and destroyed a house in which Russian soldiers were hiding

There is no choice, they explain - the distance between the two sides has become so small.

The closest, Andrii continued, had been eight metres away, when they had had to target a Russian position in like an outdoor kitchen or something. And our boys could not knock them out of there, they had to break the fence and work [attack]. And there is no other way out because it is street fighting”.

Although the IFV is the first target for enemy fire, the pair said that they don’t get frightened.

“We do not think about it, we think about civilian life, we talk, we feed our cats, which are with us, and so on, and when we receive a command – we get together and go,” Serhii said, adding, “We work together. We help each other, the main thing is not to let each other down.

“And we have no right to let the people down because they hope we will come, we will kick the Russians out of there, we will help. That is all.”

Russian forces began fighting for control of Bakhmut, in the Donetsk region, in the second half of August 2022. Mercenaries from Russia’s private military company Wagner, declared a transnational criminal organisation by the US, occupied several houses on the outskirts of the city.

Half-a-year on, the fight to control what remains of the city has turned into the bloodiest and longest battle since Russia’s full-scale invasion began.

After months of no significant military victory, Bakhmut is as much a political prize as a military one.

Kyiv has pledged to defend what President Volodymyr Zelensky described as Fortress Bakhmut after a late December visit. Rock band Antytila even recorded a song, Bakhmut Fortress, which racked 5.5 million views on YouTube in three weeks.

In late February, I made my sixth visit to the city since the full-scale invasion began. Police, border guards, territorial defence and other volunteer formations have arrived in support of the armed forces of Ukraine: Russian mercenaries and paratroopers storm the city day and night.

THE “PEAKY BLINDERS”

They call themselves the Peaky Blinders, as per the popular BBC series. It is also the name of the Telegram channel where Kharkiv-born brothers Anton and Sasha post videos of their fighting in Bakhmut, in particular guiding artillery-loaded drones. Neither of them ever envisioned a life on the frontline: 32-year-old Anton worked in construction, while Sasha, 30, was a farmer.

Based in Kostiantynivka, about 30 km west of Bakhmut, the two now serve in the National Guard Omega special unit, which operates under the interior ministry.

“We lose two or three Mavics [quadcopter drones] a week,” Anton told IWPR, referring to China-manufactured DJI UAVs. Intended for personal and commercial photography and videography, the Mavics are nevertheless widely used by Ukrainians on the frontline.

I drive up to one of the two-story buildings near the entrance to Bakhmut together with the two brothers, as mortars explode a few kilometers to the north.

While Anton and Sasha search for Russian positions, it starts snowing. The visibility is substantially reduced but it does not affect the artillery. Both sides continue to fire.

“There are probably 100 or more copters in Bakhmut right now, everyone has some sector and tasks,” Anton explained. “REBs [electronic warfare systems], anti-drone rifles, both ours and theirs, are working very actively.”

Drones carry artillery and are often attached to fragmentation grenade launcher shots for use against Russian infantry, tanks or other armoured vehicles.

Ukrainian mortars operate 200 metres from the building where Anton and Sasha operate their drones. Using a walkie-talkie, the Peaky Blinders communicate the coordinates of the Russian forces to the operators who then fire the mortars.

One of the mortar operators explains that when he joined up in 2021, army service looked very different.

“Well, we stood at the checkpoint, and watched women riding bicycles on the other side of the Ukrainian-Russian border,” he recalled. “Our whole preparation was like, ‘Good afternoon, where are you going?’ We were checking documents and people at the checkpoint. Everything we needed to learn, we learnt it here, during this first year of war.”

As we talk, a Grad projectile from a Soviet 122 mm multiple launch rocket system hits the corner of a building located two houses away from us. We run into a basement for cover; two more missiles fall a little further away, and we venture out again.

“THE ZERO”

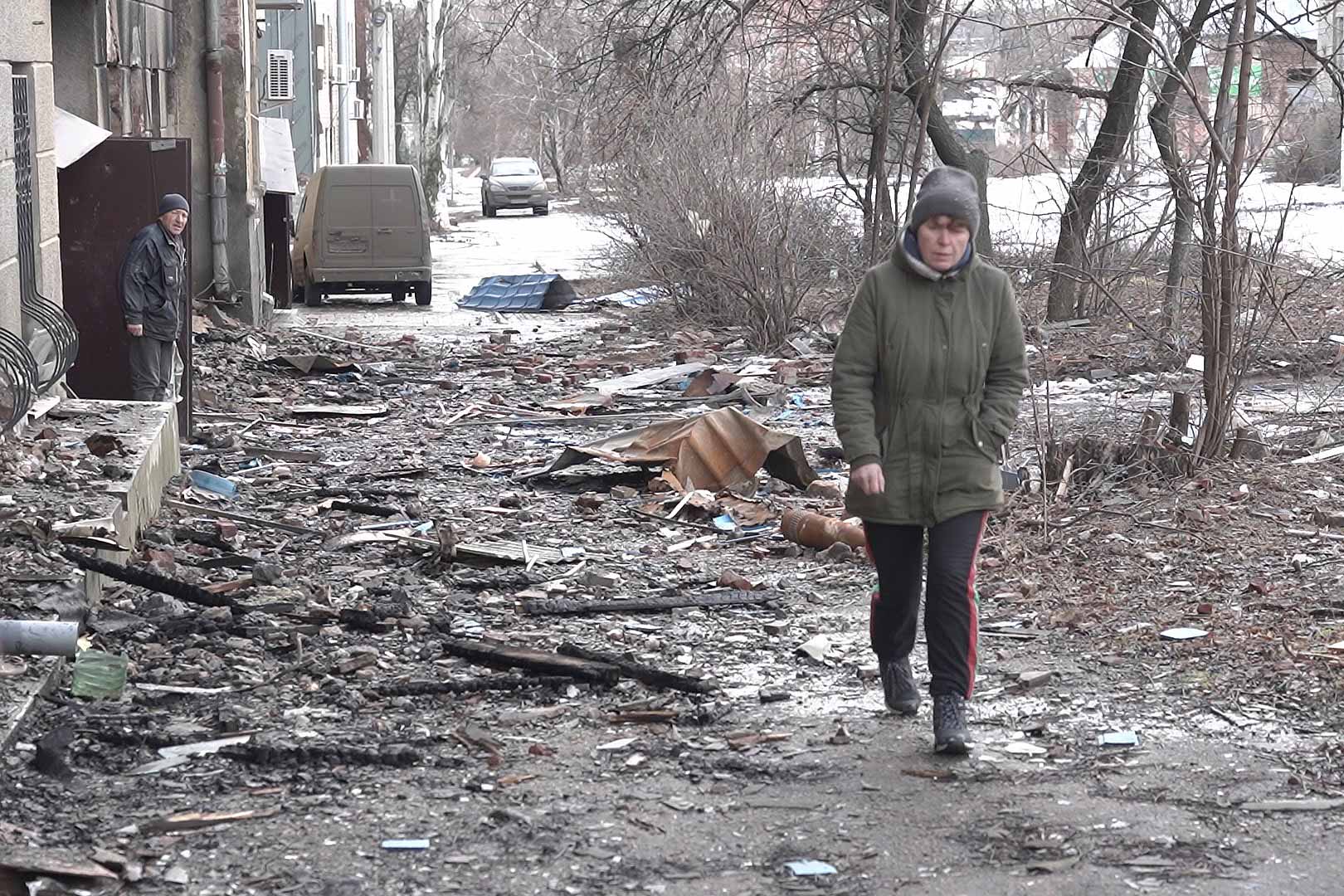

As I move deeper into the city, Bakhmut resembles a ghost town. It looks empty, although thousands of troops are stationed here. Several Ukrainian military armoured cars rush by and disappear into the side streets.

I pass the charred houses of the central square, en route to the river, which marks the frontline. The Russians are only 600 metres away.

UAF’s 93rd brigade are holding this section of the line, their third round over the last 12 months.

I meet a group of ten soldiers who were mobilised a month ago: they got 30 days of training and were then dispatched to Bakhmut. They had a day to adjust before being sent to what is known as “the zero” - the first contact line, beyond whichliesis wasteland and the Russians.

“The positions of our guys are 200 metres from here,” one said. “And to the Russians — well, it is less than a kilometre: 300 metres to the river and 300 more beyond the river.”

A woman walks past us. She still lives here, in the same house as before the war. She is one of around 4,500 people remaining of the 73,000 residents living here in February 2022. Nearly 40 children still live here too.

The woman exclaimed, “A bullet just flew past me!”

An experienced fighter, call-name Parliament, explains that this is not unusual.

“Everything flies here already, it is almost the zero. And AGS [automatic grenade systems]. And bullets, and mines, and drones fly, bombs are dropped on our heads, it happens,” he said.

I climb the stairs to the first floor of the house. There, in what used to be someone’s living rooms, soldiers are sitting near the fireplace and warming up. These are the new arrivals, heading to the zero soon, and they are nervous.

“In the morning, all ten of them did not want to go to the front, but we talked to them. Eight people want it now, but two still do not,” Parliament said. “Everyone is scared, but what [can you do] — it is necessary to do the work, and then we all will return to our women. We will get some rest.”

War reporter Anastasia Stanko is 2018 laureate of the International Press Freedom Awards of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).