What’s Behind Georgia’s “Foreign Agents” Law?

IWPR Caucasus director explains the background to the controversial legislation – and what may lie ahead.

What is the foreign agent law?

The bill was first introduced in March last year. The initial version mandated non-for-profit, NGO and media outlets that received foreign funding to register as Agents of Foreign Influence. That bill was withdrawn on March 9 due to public protest and international pressure. Critics accused the government of mimicking autocracies such as Russia in an attempt to silence opposition, critical civil society and independent media.

The leaders of the ruling party vowed never to reintroduce the law again. The reasons for breaking the promise now are not clear, but there are some indications as to the leadership’s motivation.

Georgian Dream (GD), which has a majority in parliament and fully controls the judiciary and executive branches, has been in power for 12 years, longer than any other party since Georgia gained independence in 1991.

Its leadership has claimed credit for securing visa-free travel to the Schengen Zone in March 2017, obtaining EU candidacy status in December 2023, qualifying for Euro 2024 - and avoiding armed conflict, especially after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

GD, founded and currently chaired by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishivli, also enjoys support from the country’s most trusted institutions: the army, the church and the police. The latest polls by the International Republican Institute indicated that the GD is ahead of its major rival, the United National Movement (UNM) founded by former president Mikheil Saakashvili, who is currently imprisoned.

With all these favourable conditions ahead of upcoming parliamentary elections in October, GD may be leveraging political capital to target the UNM, its longstanding rival.

“After the elections the national movement will be made responsible for all the crimes it committed against the Georgian state and Georgian people over two decades,” said Ivanishvili during his speech at an April 29 rally in response to the protests against the reintroduced foreign agents bill.

Other reasons for reintroducing the law could be linked to anticipation that Ivanishvili and his close associates might soon face sanctions.

In October 2022, Ukraine sanctioned his close family members and relatives and continues to advocate sanctioning Ivanishvili himself. Other figures have been sanctioned, including US state department measures against four senior judicial officials close to the GD leadership in April last year.

On April 22, the European Parliament called for sanctions against all members of the Georgian parliament who voted in favour of the bill, as well as proposing sanctions against Ivanishvili himself.

In addition, parliament approved another controversial amendment to the tax code while the country was protesting against the Foreign Influence bill.

Passed through expedited procedures on April 19, these offer tax benefits to companies and individuals who transfer their assets from tax haven offshore zones to Georgia. Some experts think that this will help the billionaire and his proxies to move assets if sanctions are imposed.

Another resource could be the gold purchases added to Georgia’s currency reserves. In March this year the National Bank of Georgia (NBG) purchased seven tonnes of monetary gold worth 500 million US dollars. The volume of purchased gold amounts to 11 per cent of the NBG's international reserves, according to the bank. This could be another mechanism to withstand anticipated wider institutional sanctions.

Furthermore, in April this year, Georgia and China reached an agreement on visa-free travel, effective from May 28. This development follows the establishment of a strategic partnership between the two countries in August last year, backed by a free trade agreement concluded in May 2017.

In May 2023, Russia also lifted restrictions and introduced visa-free travel with Georgia, which had been imposed by Moscow since the Russian-Georgian war in August 2008.

Lastly, the law’s reintroduction was coupled with two other legislative proposals: abolishing gender quotas introduced in 2019 to encourage women to become legislators, and introducing a constitutional amendment to counter LGBTQ so-called propaganda allegedly sponsored by Western donors and NGOs.

These two moves suggest a strategic attempt by the government to appeal to conservative and patriarchal sentiments prevalent in Georgian society to undermine critical civil society and media outlets and win electoral support in October.

How has the government reacted to the demonstrations?

The government is using disproportionate police force against the protesters, predominantly aged 15 to 30.

Lawmakers from the ruling party are harassing opposition politicians – often women - with appalling verbal and physical aggression.

Protesters who are identified by the police are subsequently arrested at their homes. Some receive threatening anonymous phone calls warning them to stop attending the protests.

Widespread gendered disinformation has also been spread through social media, orchestrated by government-affiliated trolls who manipulate authentic images.

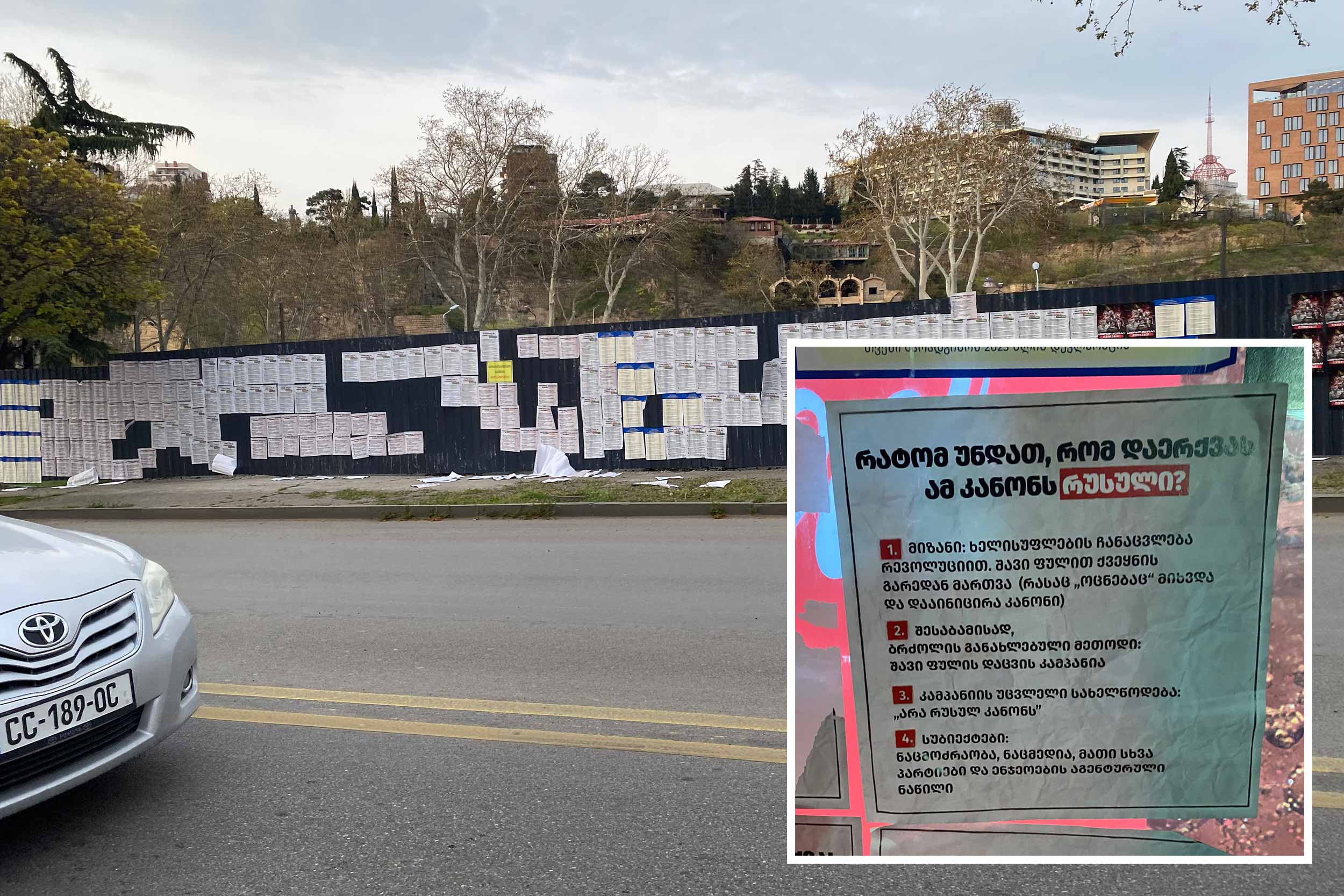

A smear campaign has targeted prominent political, civil society and media figures, employing propaganda tactics such as posters plastered across bus stations and fences labelling them traitors.

What has been the reaction from Georgia's western partners - and the Kremlin?

Western partners, including EU and NATO member states, along with intergovernmental organisations like OSCE, UN and COE, as well as international human rights groups, have urged the government to refrain from enacting the proposed bill into law and allow for further debate.

The only statements of praise have come from Kremlin officials, including its mastermind ideologist Aleksander Dugin.

“Georgia is on a right path. You want a sovereignty, eliminate the fifth column. There are so many liberal agents in the country … with the help of God we will wipe them all out,” Dugin posted on his Telegram channel.

Georgia's President Salome Zourabichvili has reiterated her intention to veto the law, as she has done with the recent legislation concerning the abolition of Gender Quotas or amendments to the tax code regarding asset transfers from tax havens.

However, the ruling GD party holds a parliamentary majority, enabling it to overcome the veto. While the veto may delay the enactment of the law, it is not sufficient to prevent it from being passed eventually.

What does the bill mean for Georgia's civil society?

If the law is enacted the majority of watchdog organisations may vanish. In the short term, the most important issue is to ensure that election monitoring NGOs can remain active for the parliamentary polls in October.

Most of Georgia’s civil society organisations have been clear that they will refuse to register as foreign agents.

This suggests that most humanitarian and developmental efforts will be compromised, at least for some time. Judicial and policing processes will largely remain unmonitored. Disinformation and other forms of malign interference will also mostly go unchecked, creating room for the proliferation of media, investment and pseudo-civil society initiatives representing non-democratic countries like Russia.

What are the implications for the autumn elections?

The implementation of the Law on Foreign Influence may pose significant challenges for the oldest and most experienced independent election watchdog organisations. They could also become targets of smear campaigns, potentially discouraging observers from volunteering for election monitoring. Independent news agencies may also face challenges.

The mobilisation of administrative resources is another critical factor. The recent pro-government rally on April 29, held in response to protests against the proposed bill, demonstrated the government's mastery in quickly mobilising supporters from even the most remote regions.

This year, for the first time, Georgia will introduce electronic voting devices in 90 per cent of precincts. Uncertainties remain regarding the reliability of the IT infrastructure to handle the anticipated high usage, as well as the literacy levels of voters and election administrators in utilising this technology effectively. Without robust security measures, electronic voting systems are vulnerable to fraud.

Finally, it is crucial to note that the ongoing crisis could lead to increased malign interference from Russia in the election and other governance processes.

Have other countries in the former Soviet Union space followed Russia’s example and approved similar bills?

Russia’s law example initially targeted only NGOs receiving foreign funding. Since its adoption in 2012, it has expanded to include media, individuals and any other legal or public entity engaged in vaguely defined “political activities”.

A similar trend is occurring in other countries that introduced such laws. Initially, these laws target civil society, followed by restrictions imposed on media organisations.

For example, the latest version of the Kyrgyz law, approved in March this year, mandates NGOs funded from external sources to apply to a public register of “foreign representatives” if they engage in activities defined by the law as “political”. The definition of “political activities” aligns with the Russian one introduced as an amendment to the law on foreign agents in January 2016.

In Ukraine there were attempts to introduce the modalities of the Russia and Belarus style laws on foreign agents and extremism in 2014 under Victor Yanukovych. Shortly after the Maidan protests the bill was withdrawn. However, it resurfaced periodically with the support of pro-Russian political factions in the Ukrainian parliament before the Russian full-scale invasion in 2022.

In Kazakstan human rights, media, and election monitoring NGOs are mandated by law to report foreign funding to the tax authorities. Any mistake is subject to harsh penalties. Last year the government publicised a register listing organisations and individuals who receive foreign funding. Civil rights groups have urged the authorities to scrap the register, warning it echoes Russia's prelude to its 2012 foreign agent law.

Beyond the former Soviet Union space but targeted by Russia's influence, Republika Srpska is gearing up to introduce a similar law. The April 3 bill specifically targets foreign-funded non-profit organisations, to be overseen by the ministry of justice. Like Georgia, lawmakers assert that it is inspired by the US Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).