A World in 30 Metres: Kyrgyzstan’s Rural Libraries

Precious resources are often villages’ only cultural centres, but they remain underfunded and at risk.

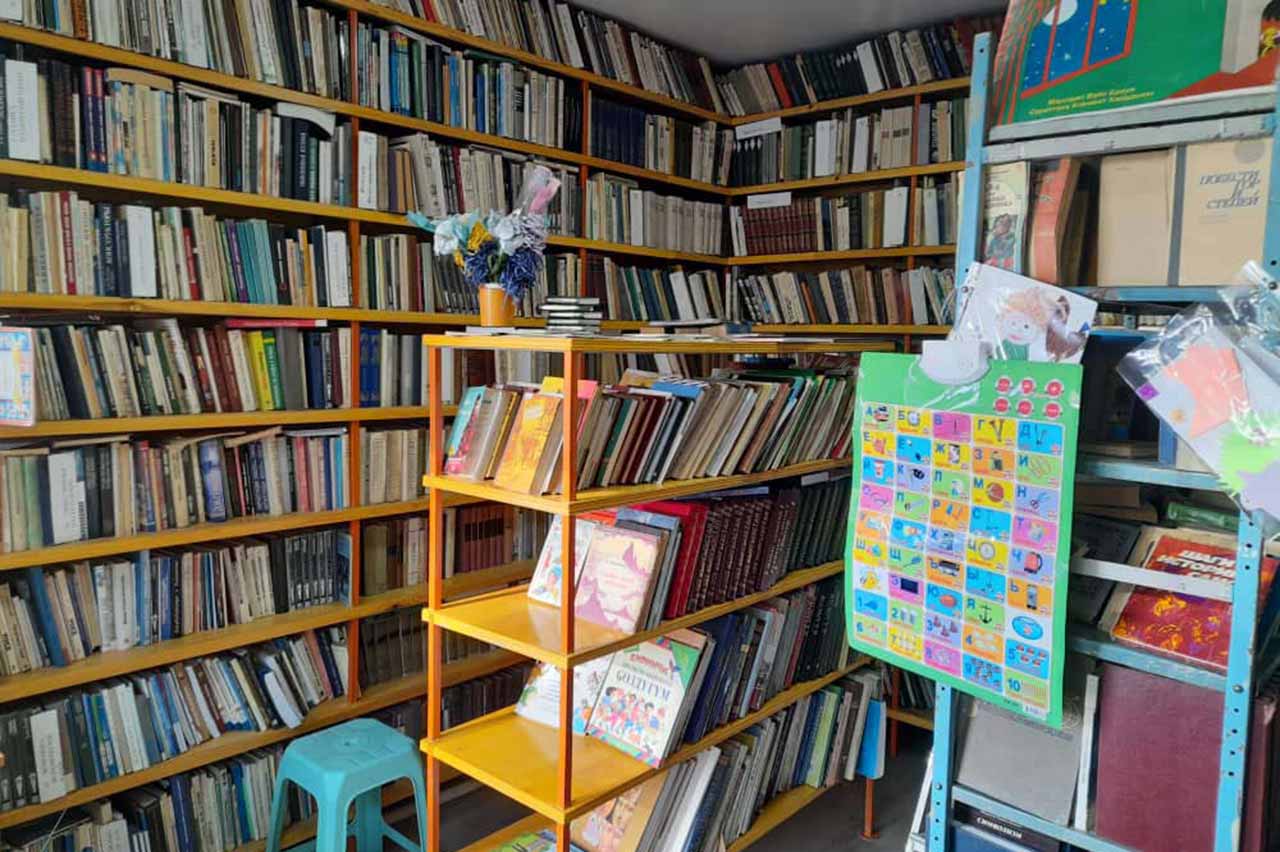

About 5,000 Kyrgyz, Russian and English language books are packed onto two racks and ten shelves that make up the library in the village of Zharbash in northern Kyrgyzstan.

It’s not much, acknowledges Nasip Urmatbek kyzy, the library’s only employee - and thus director, librarian and cleaner- but “this is better than nothing,” she said. Urmatbek kyzy is nonetheless proud of the 30-square-metre space and draws particular attention to the full collection of novels by Chyngyz Aitmatov, one of Kyrgyzstan’s leading writers.

Built in 2020 in a prefabricated structure, the library acts as the cultural hub for Zharbash, located in the Chul region. It is free, accessible to everyone and open all day. But it lacks internet access, which would transform the facility as most households in the village do not have internet connection.

“If we had the internet, we could print out colouring books for children, find interesting information for students, download e-books and disseminate them among children,” Urmatbek kyzy said, adding, “I want this space to be useful to all residents, aa place for extra activities for schoolchildren or kids who do not attend kindergarten.”

The Zharbash library is one of many hundreds of such institutions playing a vital educational role across the country, but which often lack the badly-needed resources that would allow them to offer key benefits to local communities.

“Over 80 per cent of the 1,060 libraries in Kyrgyzstan are located in rural areas,” said Rinat As karbekov, head of the cultural heritage section of the ministry of culture, information, sport and youth policy. He added that in some villages, they are the only source of information available.

Computers are a rare commodity in rural areas as are domestic internet connections, making access through libraries even more relevant.

NOT ENOUGH BOOKS

While the ministry of culture manages 12 large libraries, almost all other facilities depend on local authorities, which are in charge of allocating the funds.

The resources for acquiring books remains meagre. In 2022, for example, the Zharbash library procured just over 40 books, largely Russian-language fiction. The book publishing sector in Kyrgyz language is limited.

“Readers, including children, ask for books on self-development in Kyrgyz, but we don’t have such books…To meet some requests, I go to the Chuy regional library and look for books there or search for an electronic format [on the internet],” Urmatbek kyzy said.

In the village of Orlovka, also in Chuy region, the local library manager Kulmira Kurmankulova has a budget of just under 20,000 som (about 230 US dollars) which barely stretches to cover essential office supplies, let alone books.

“We spend this money to buy stationery and household goods, but we file requests for additional funding. My request for internet access was approved; hopefully we will get it next quarter,” Kurmankulova told IWPR.

The total national book fund is nearly 20 million books, about three per citizen. This is not enough, maintained Oleg Bondarenko, executive director of the Association of Book Publishers and Booksellers.

“It is critically insufficient given that over a half of the books are of Soviet Union heritage,” he told IWPR. “They are good but statistics show that they are read less often. The demand now is for modern literature, new books with recent research in medicine, construction, business. We should also not forget children’s books with vivid illustrations and pictures... But libraries are not regularly replenished and, when they are, the supply is insufficient anyway.”

Rural libraries should focus on Kyrgyz-language children's content as they were critical in shaping their development, he noted; the state should be more active and should fund the translation, publishing and distribution of popular books across the regions.

“A book is not just a text, it is art."

“What development and maintenance can we speak about if [libraries] have 20,000 som per year and 40 to 50 new books in their fund?” he said.

Since independence in 1991, book publishing has dived due to declining demand. On average, about 700,000 books are published annually in Kyrgyzstan, in 800 to 1,000 categories, compared to the nearly ten million per year released in Soviet Kyrgyzstan until 1990.

A few international organisations, like the US development agency USAID, have projects in this field but far more work was needed, continued Bondarenko.

According to the ministry of culture, every year nearly 40,000 books are sent to regional libraries; they include novels by foreign authors translated into Kyrgyz, motivational books and specialised literature.

“Libraries are replenished in a number of ways. The ministry procures them; also, every [Kyrgyz] author must supply 12 copies of their new books to the National Book Chamber, which then disseminates them among libraries,” Bakeev said, referring to the state institution managing all publishing activities in the country, including cataloging and archiving. “We are also trying to increase funding.”

The ministry of education has also established development centres in 120 libraries across the country.

“Our purpose is to make libraries cultural and educational spaces, where various events and courses can be held both for children and for adults,” the ministry’s press secretary Nurzhigit Myrzabekov told IWPR.

SHINING STARS

Despite the challenges, some local libraries are managing to deliver essential services to their local communities. The Chuy regional library in Kant, a town of 23,000 about 23 kilometres west of the capital Bishkek, is an example of just what can be achieved with the right facilities.

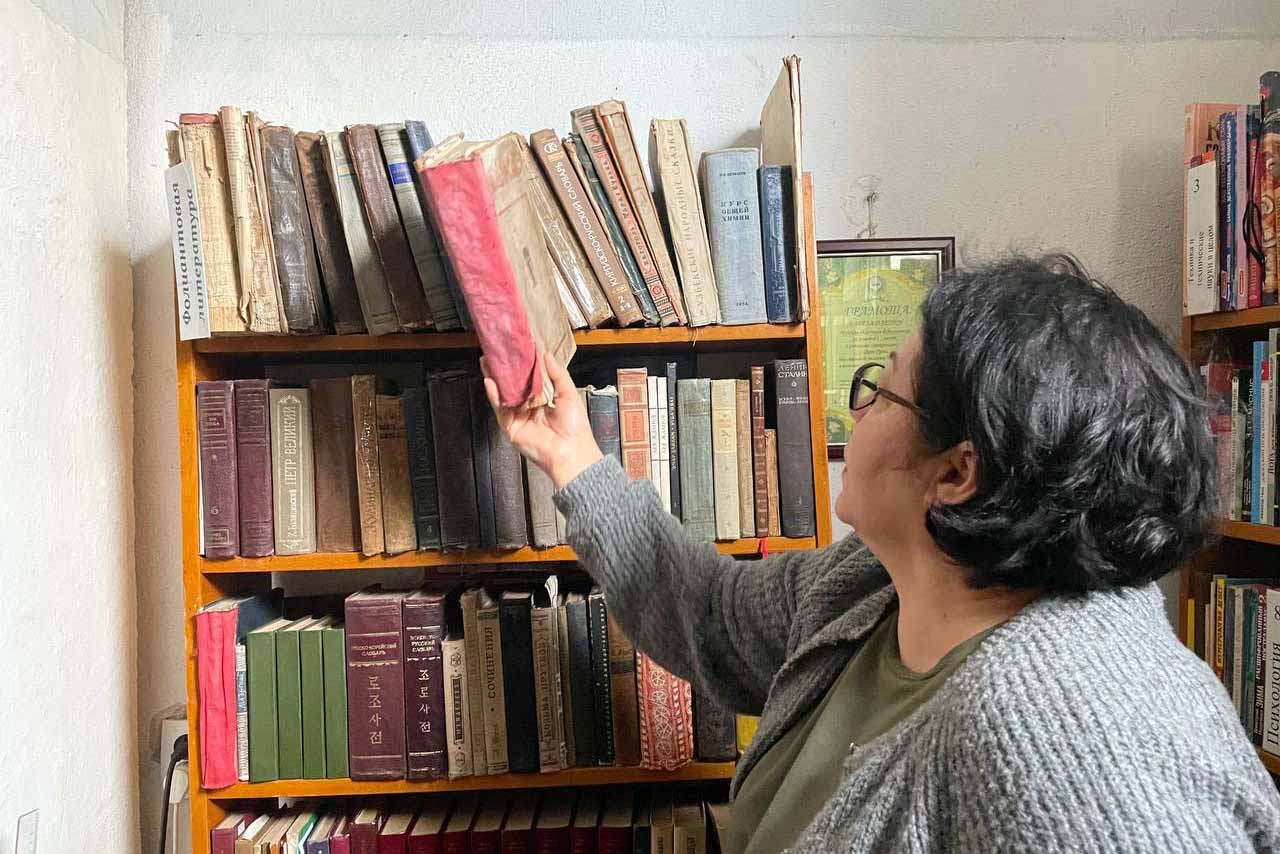

The library is multifunctional, with computers, internet access and a large and varied stock, including bestsellers of modern literature. It also features rare books, including a copy of the Old Testament published back in the 18th century in Old Slavonic, the first Slavic literary language.

“If you are looking for recipes of bread, pie or fish soup, like in the Soviet-time canteen, you can find them all here,” director Tamila Kadzhieva told IWPR as she walked along the shelves indicating books to her left and right.

“Students and adults alike come here to read. Everything is free of charge. Libraries are windows to other worlds and our mission is to explain and show the reader that the world is interesting and you can start exploring it here,” Kadzhieva said.

Kyrgyzstan also has an electronic library with over 1,500 books in digital form, including children’s books like novels and encyclopedias.

“These are all available both in Russian and in Kyrgyz. The electronic library can be installed on a PC and used without the internet. This is a good opportunity for children from remote villages,” Kadzhieva added.

In Dmitrievka, a village on the border with Kazakstan also in the Chuy region, Altynchach Ospanova has made the growth of the local library her personal mission.

In 2022, the library comprised a room with a few hundred books; one year later it has become a hub for young people in the area. Local parents help with site maintenance and building materials.

“I raised money from the local municipality to buy a computer and get access to the internet,” Ospanova, who is also deputy in the kenesh, the local assembly, told IWPR. “This year, an additional office was allocated for the development centre [with clubs and courses for children]. Parents are thankful to have a place where their children can come.”

She added that it was vital for the state to maintain libraries and open new ones, despite apparently declining interest.

“Libraries help children and adult readers to see books as a cultural phenomenon,” she said. “A book is not just a text, it is art: think of the printing, the illustration… where else can we encounter them?”

This publication was prepared under the "Amplify, Verify, Engage (AVE) Project" implemented with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway.