Turkey and Central Asia’s Growing Partnership

Erdoğan’s win marks continuity in Turkish economic and political engagement with the region.

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recent election win has been closely followed in Central Asia, where Ankara’s economic and political influence has risen considerably over the last decade.

The run-off, Turkey’s first ever, followed the most closely fought presidential vote in the country’s history and secured the incumbent’s win against opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu.

Erdogan now looks set to continue a regional policy that has included expanding trade and economic cooperation, improving connectivity and reaching markets in Central Asia and beyond.

In the increasingly unstable geopolitical landscape created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Turkey has also sought to carve out a diplomatic and military role that has extended to Central Asia through trade and defence agreements.

“Ankara has intensified relations since 2020… It will become a significant partner of our regional states in near future, competing with Russia and China,” Tajik political analyst Sherali Rizoyon told IWPR.

Since independence in 1991, the Central Asian republics have pursed a multi-vector foreign policy to balance the major powers and Turkey is seen as a relevant partner to counter the penetration of Russia and China in the region.

“Central Asia will benefit from [his win] because Turkey is one of the directions in the region’s declared multi-vector foreign policy. Ankara is not trying to affect this vector by enforcing its course or friendship against someone,” Aman Saliev, director of the Bishkek-based Institute of Strategic Analysis and Forecasting, told IWPR, adding that Erdoğan was a known quantity and thus his win meant stability, or at least predictability.

Seeking deeper cultural and economic ties after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ankara established the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TİKA) in 1991. In 2009, Erdoğan spearheaded the Cooperation Council of the Turkic Speaking States, which was renamed the Organisation of Turkic States in 2021.

The bloc features five member countries, Azerbaijan, Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan, and two observer states, Hungary and Turkmenistan. Combined, they are home to around 170 million people and have a gross domestic product (GDP) of nearly 1.5 trillion US dollars, while the trade volume among them is estimated at 16 billion dollars.

Erdoğan’s re-election win will cement policies to increase energy supplies from the region and secure transit and access to markets in Asia.

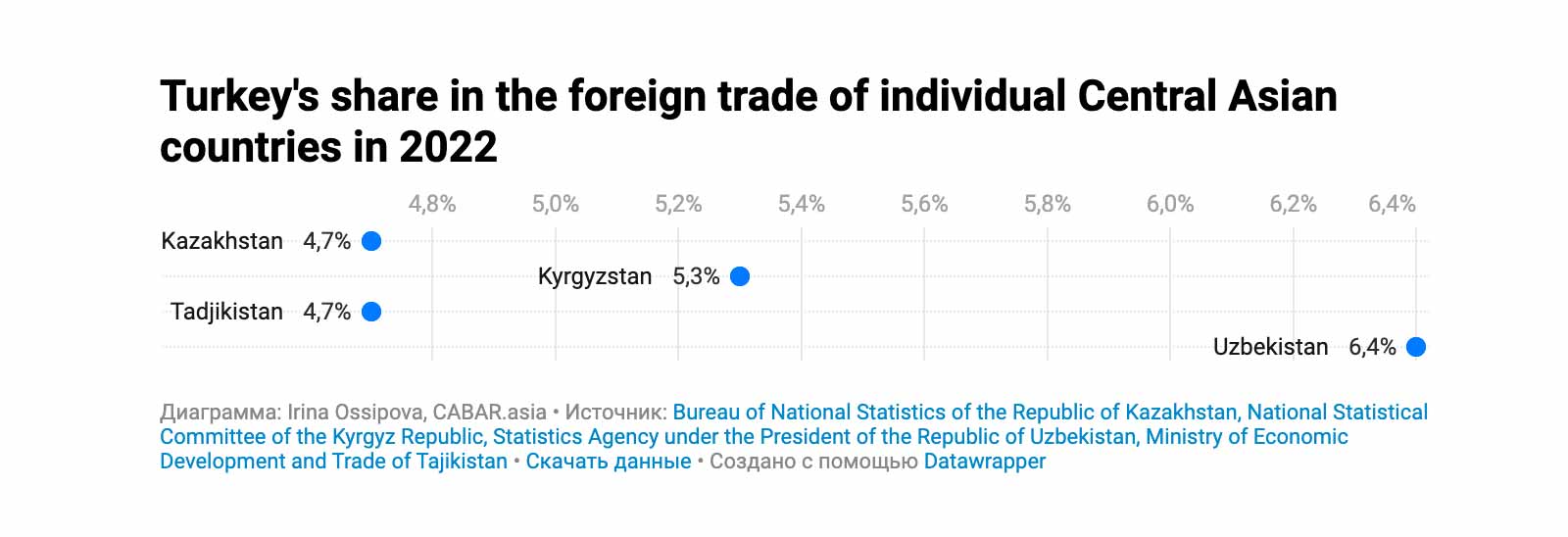

The Central Asian republics’ share of the trade turnover with Turkey is high – 4.7 per cent in Kazakstan and Tajikistan, 5.3 per cent in Kyrgyzstan and 6.4 per cent in Uzbekistan.

Despite significant gas finds in the Black Sea in 2020, Turkey depends substantially on external energy supplies as it only produces three per cent of its annual consumption.

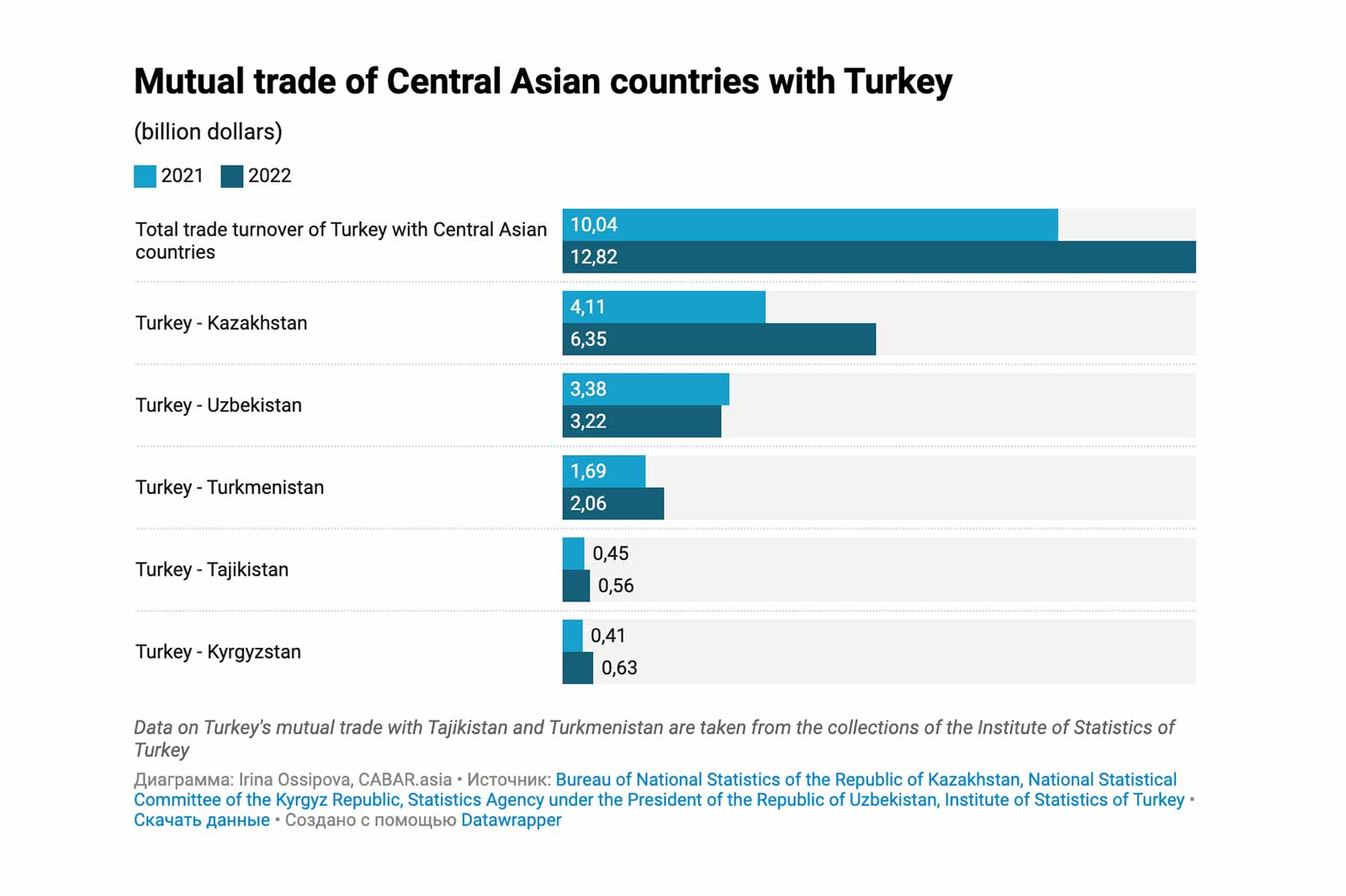

Oil and gas-rich Kazakstan is a crucial trade ally. In 2022, Astana’s turnover with Ankara amounted to 6.35 billion dollars, up by 54.5 per cent compared to the previous year. The hike mainly resulted from the rising prices of petroleum products, which amounted to over 70 per cent of Kazakstan’s export basket to Turkey.

As the war in Ukraine disrupted supply chains in the global energy markets, in 2022 Turkey’s import of coal from Kazakstan also rose by 58 per cent.

The trade turnover with Ankara increased for all republics: by 53.7 per cent for Kyrgyzstan, by 23.3 per cent for Tajikistan and by 21.9 per cent for Turkmenistan.

“In 2022, Tajikistan had trade relations with 109 countries of the world and Turkey has become one of Dushanbe’s top five trade partners,” Tajik political analyst Sherali Rizoyon told IWPR.

Uzbekistan was an exception, with a drop of 4.7 per cent, but the 3.2 billion dollar total turnover is the highest in the area after Kazakstan.

FROM TURKISH TO TURKIC

The change of the Cooperation Council into the Organisation of Turkic States (OTS) in 2021 was not just a formal re-naming.

Considered a sort of Turkic-speaking EU, the bloc has since added common goals and cooperation on all aspects of life, including foreign policy, migration, information technology and religion. Stressing a pan-Turkic identity, Ankara has also strengthened its soft power.

“[The bloc] has contributed to the promotion of Turkey’s image on the world stage, and keeping this positive image is its permanent value,” Uzbek political analyst Farkhod Tolipov told IWPR, adding that Uzbekistan’s accession in 2019 had brought relations between Tashkent and Ankara to a new level.

“It filled a gap, [the organisation] seemed incomplete without a large state [such as Uzbekistan] in the Turkic world. Ankara supported the decision and that step towards Uzbekistan helped to establish contacts not only in trade, tourism, education, but also in the field of security, military issues. It is not just a bilateral cooperation, but a strategic partnership…This is very important, I would say we should encourage it.”

Observers note that Erdoğan’s pan-Turkic policies would bring Central Asia and Turkey closer.

“This [pan-Turkism]is particularly appealing to Turkic-speaking countries,” noted Chinara Esengul, a Bishkek-based international relations analyst. “We should not ignore the [regional] dependence on Russia, which affects the nature and dynamics of relations between the region and Ankara…These choices are so important because global system transformation is taking place now… Turkey, Russia and China will become extremely important for Central Asian states.”

This publication was prepared under the "Amplify, Verify, Engage (AVE) Project" implemented with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway.