How Uganda Tried to Silence Protest

Young anti-corruption activists tell IWPR of abuse they suffered in police detention.

“I expected to be killed. I expected to be raped,” said Aloikin Praise Opoloje, a few days after she was released from detention on bail in August this year.

The 25-year-old law student had been arrested, along with dozens of others, after taking part in an anti-corruption protest in Kampala on 23 July. During the arrest, one male police officer had put his hands between her legs and squeezed her genitals. Female officers had pulled her ponytail backwards and throttled her.

At the Central Police Station in Kampala, where most of the arrestees were temporarily held, officers attacked Opoloje and her companions, slapping, kicking and hitting them with batons all over their bodies.

“These are the ones distracting [sic] the peace that we have here?” one officer asked rhetorically. “Who has paid you to protest?”

That day alone, over 100 mostly young protestors were arrested, denied bail and detained for close to two weeks. Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, ministers, and social media accounts belonging to ruling party supporters all claimed that the protestors had been funded by foreign actors to bring down the government.

IWPR has interviewed a dozen protesters arrested on July 23, who – like Opoloje – all gave accounts of being physically abused in detention. Some suffered serious injuries that they have yet to recover from. They deny any link to foreign funding and say they merely wanted to state their opposition to corruption in Uganda – which ranks 141 among the 180 countries in Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index.

Instead, they say, they were systematically abused and labelled enemies of Uganda. To date, none of the alleged perpetrators have been held accountable.

“Playing With Fire”

Like many Ugandans, Opoloje was enraged by revelations earlier this year that government officials had been siphoning off billions of dollars’ worth of public funds for their own personal use. But the fact that parliament’s speaker and deputy speaker had procured generators for their homes at inflated prices made it personal: at the start of the year, Opoloje had given birth in a rural hospital, where she and her baby almost died due to shortages and a power cut.

Opoloje started making videos about corruption and posting them on her social media accounts. She made contact with other like-minded young people, organising discussions on X/Twitter Spaces to generate ideas on how to protest.

As a law student, Opoloje scrupulously suggested that they notify the police of their intent to protest. On July 12, inspired partly by Kenya’s protests against the cost of living, the group wrote to the Kampala Metropolitan Police, saying they intended to lead a demonstration to parliament. Their key demand was that the speaker, Anita Among, resign.

The police responded by threatening them and ordering them not to hold the protest. On July 21, Museveni warned the activists that they would be “playing with fire” if they went ahead.

“But by then,” Opoloje said, “I had no returning point. We had our demands and those were our demands: Anita must resign.”

On the day itself, Opoloje and a group of 25 others gathered at Garden City shopping mall, a few hundred metres away from parliament. Within minutes, police were deployed in the area. Suspecting that someone had tipped off the authorities, the group separated and moved to another street close to parliament. They pulled out their placards and started protesting.

Police officers quickly surrounded them and started making arrests. Throughout the day, other youths who had gathered in other parts of the city were also rounded up in the same way as they tried to protest.

It was after the arrests, at the Central Police Station, that mistreatment began in earnest. George Victor Otieno, another university student, tried to reason with officers, explaining that corruption cost Uganda dearly and resulted in government employees like themselves being badly paid.

“Why are you making a lot of noise here? Keep quiet,” shouted a senior officer, before adding, “Take this gentleman away.”

Otieno, Opoloje and other arrestees later identified the senior officer as Joel Ntabu, commander of the Kampala Metropolitan Police criminal investigations directorate, after his picture appeared on social media.

When the group arrived at the police station, having heard countless reports of torture in the cells, they had devised a plan to stay together. They held onto each other in order to stop officers from separating them.

Ntabu ordered several policemen to come and drag Otieno to one of the rooms and for Opoloje be taken to another room.

“Make sure you do everything he tells you to do, because if you don't do it, he's going to kill you,” a female police officer told her.

“I asked, ‘Why would he kill me? What have I done wrong?’” Opoloje recalled. “I said, ‘I have done nothing wrong. I am just protesting, which is my constitutional right.’”

Once she had been taken to the room, Ntabu immediately started slapping Opoloje. There were some benches and tables in one corner of the room. Ntabu pushed her into the tables, pulled her back and started slapping her again. She just kept crying and looking at him.

Later, another officer brought her a sheet of paper on which to make a statement. But by this time, Opoloje said, she had been beaten so much she was no longer afraid.

She declined to make a statement, insisting that she could only do this in the presence of her lawyer. The police officers, led by Ntabu, decided to take her to another room and torture her further.

As they were taking her, Opoloje saw Otieno again. He was lying on the floor, his shirt in tatters, and a police officer was kicking him.

“This man subjected me to a kind of torture I could only imagine, the kind of Russian-style thing that you see and hear people speaking of,” Otieno told IWPR.

He said that the officers demanded he make a statement admitting he was being funded by foreign organisations and that he worked closely with Bobi Wine, Uganda’s leading opposition politician – who Otieno had never even met.

“I was showered with beatings of batons. To date I have marks on my body,” he said. “I was kicked in my genitals while I was in that office. I lost my breath to the point that I was almost ready to give up and do everything they were telling me.”

Otieno added that most of his fellow arrestees were treated in the same manner.

“Very Bad Things”

Reports of cruel treatment started emerging on X/Twitter the day after the protesters were arrested from friends and family who had visited them in detention. Initially denied bail, most arrestees were released a fortnight later amid mounting public pressure.

All 12 protesters who spoke to IWPR named Ntabu as a key perpetrator. Luke Owoyesigyire, the deputy spokesperson for Kampala Metropolitan Police, denied that Ntabu was involved. He told journalists on August 5 that Ntabu’s role was limited to supervising case files and that he did not conduct interrogations.

Most of the arrestees, however, say Ntabu beat them while trying to force them to make statements in the absence of their lawyers. Rather than offer to conduct a criminal investigation into their treatment, Kampala Metropolitan Police advised the protesters to make a formal complaint to the Uganda Human Rights Commission.

Eron Kiiza, a human rights lawyer who specialises in police violence cases and who is representing some of the protesters, said that the claims of mistreatment already made public should have been enough to prompt an investigation.

“If police heard from the public that there was a terrorist group in a certain area,” Kiiza asked, “Would they sit back and wait for a formal complaint? The job of police is to detect crime, investigate it and apprehend the culprits. In this case the police know what happened, but they are simply not interested.”

Gideon Nova Kwikiriza, president of the activist group Ugandans on X, who was also arrested and beaten up in the cells, pointed out the irony that in other circumstances Ugandans can be arrested on the basis of social media posts.

“Why do you consider my complaint not formal when it is on X? Yet you use X to arrest people?” he said.

On July 25, Museveni issued a statement congratulating the security forces for halting the protests. He claimed that protesters were receiving foreign funding and that some had been planning “very bad” things against the people of Uganda.

“Those very bad things will come out in court when those arrested are being tried,” said the president. “The evidence in court will shock many.”

Physical and Mental Scars

So far, the evidence Museveni claimed to have access to has not materialised. The protesters continue to regularly appear in court as they await trial on charges of “common nuisance” – a colonial-era law that can carry a punishment of imprisonment for one year.

Meanwhile, many are still dealing with the physical and mental scars of their experiences. Opoloje has a mark on her neck from where her hair was pulled; Otieno says he now gets migraines. Kennedy Makana, another arrestee, said he developed hearing problems after being slapped on the ears. Yet another, Sadat Mugweri, is currently receiving treatment in a mental health facility.

“He told me they would pour cold water and beat him while in detention,” Mugweri’s mother told us in a phone call, explaining that he had already been battling mental health issues before the protest. “That treatment worsened his situation.”

Of the entire group of more than 100 people, Sammy Okanya - badly beaten after his arrest - has been denied bail four times and is still detained awaiting trial.

After a recent court hearing, IWPR managed to visit Okanya in the holding cells.

“I cannot currently hold urine because of the way I was tortured,” he said, adding that he had contracted tuberculosis while in prison.

His lawyer, Ishaq Olega, said that he has asked the court to release Okanya and have his alleged abusers arrested, but his request was declined.

“Everything is being handled with impunity,” he said.

Okanya believes he is being singled out because he is a vocal critic of Museveni.

“They want to instill fear in people that if they challenge the government they will be treated the same way I have been treated,” he said.

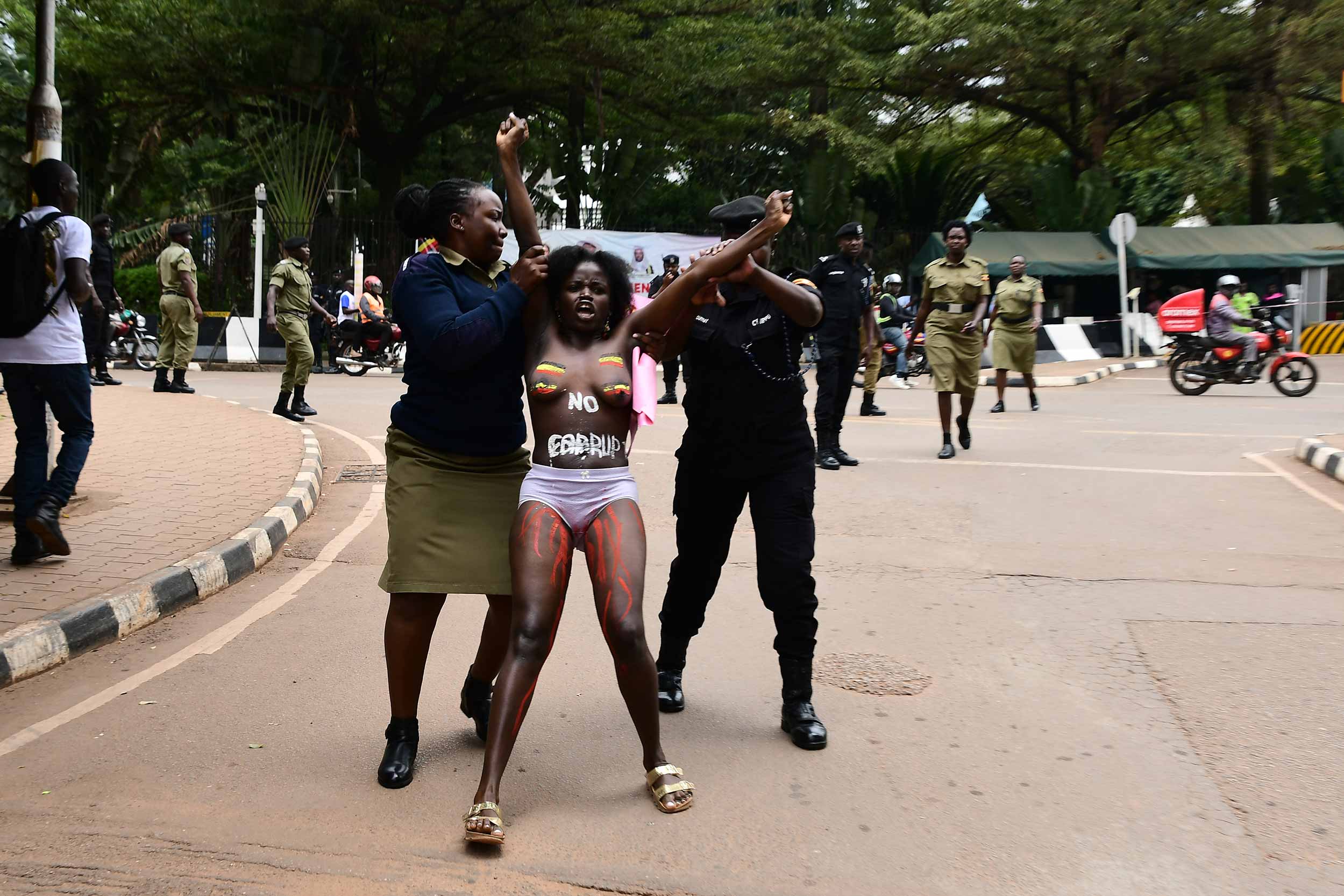

This has not deterred everyone from protesting, however. On September 2, Opoloje and two other women, Norah Kobusingye and Kemitoma Kyenzibo, marched naked towards parliament with their bodies covered in anti-corruption messages. They were immediately arrested, charged with being a public nuisance, detained, and released on bail 10 days later.

Yet Opoloje remains defiant.

“Enough is enough,” she said. “If I lose anything, I’m willing to lose it if I can add a stone to the building of a better country of Uganda.”